SURE IT’S A NUISANCE, BUT WHOSE NUISANCE?

I live near enough to Cleveland to be aware of the blight of homes abandoned there during the Great Recession. The owners leave, the banks foreclose, the homes decay, the taxes are no longer paid, and the city tries to sell them for tax debts. Many times, the city ends up owning them.

I live near enough to Cleveland to be aware of the blight of homes abandoned there during the Great Recession. The owners leave, the banks foreclose, the homes decay, the taxes are no longer paid, and the city tries to sell them for tax debts. Many times, the city ends up owning them.

Yet, Cleveland is an enclave of plenty compared to Detroit, where the blight covered mile after mile. A third of all homes in that bankrupt city had been foreclosed on by 2015.

Out of fairness, Detroit has made a real comeback. The Motor City has stabilized its financial condition, improved city services, reversed population losses that saw more than a million people leave since the 1950s and made progress cleaning up blight across its 139 square miles.

In October 2024, Donald Trump told the Detroit Economic Forum that “[t]he whole country will be like — you want to know the truth? It’ll be like Detroit. Our whole country will end up being like Detroit if [Kamala Harris is] your president.” He caught a lot of grief from Detroiters for that. Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan said, “Lots of cities should be like Detroit. And we did it all without Trump’s help.”

So who is responsible for the nuisances that these decaying homes (and untrimmed foliage) create? Generally, it’s the owner or the entity with the right to control the property. In today’s case, decided when I was not yet a teen, a city argued that it owned and controlled an abandoned property for some purposes, but not where abating a nuisance was concerned.

Neighbor Harry Homeowner, who was beaned on the noggin by a branch from a dead tree on the neighboring lot, disagreed. “Hey,” Harry huffed, “if you own it, you own it.”

Kurtigian v. Worcester, 203 N.E.2d 692 (Supreme Jud. Ct., Mass. 1965). Harry Kurtigian was working in his yard one windy October day in 1959 when he was struck by a limb blown from a decayed tree on adjoining property.

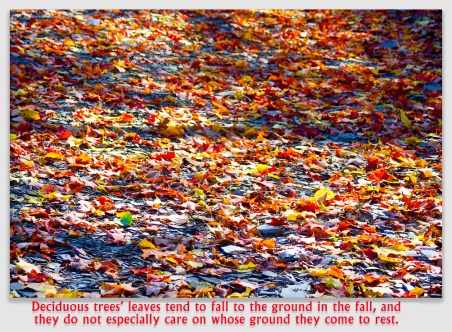

A large elm tree was situated in the southeast corner of the lot next to Harry’s, one which had been owned by Beatrice R. Norling. By 1954, Beatrice was dead, and the tree was soon to follow, having been afflicted with Dutch elm disease. By 1956, there were no leaves on the 35-foot tall tree at all, and the bark was peeling from the trunk by year’s end.

Two years later, a large branch fell during a summer thunderstorm, crushing Harry’s fence. He called the City, who sent an inspector to look at the tree. About 15 months later, the tree still standing undisturbed, Harry was walking in his yard when he heard a cracking sound, looked up, and saw a heavy limb falling toward him. He was knocked unconscious, suffering a skull, arm and wrist fracture.

Two years later, a large branch fell during a summer thunderstorm, crushing Harry’s fence. He called the City, who sent an inspector to look at the tree. About 15 months later, the tree still standing undisturbed, Harry was walking in his yard when he heard a cracking sound, looked up, and saw a heavy limb falling toward him. He was knocked unconscious, suffering a skull, arm and wrist fracture.

The lot next door was undeveloped and wooded, having been acquired by the City of Worcester in 1950 for nonpayment of taxes. Harry sued the City for negligence and for maintaining a nuisance tree,

The lower court found the City was negligent, but that the tree was not a nuisance. The City appealed.

Held: The tree was a nuisance, and the City was liable to Harry.

Liability for damage caused by the defective condition of premises turns upon whether a defendant was in control, either through ownership or otherwise. The City argued that it did not have title to and control of the real estate. But the records showed that the City recorded in the registry of deeds an instrument of taking in August 1950, pursuant to law for nonpayment of taxes. Three years later, the City recorded a notice of foreclosure, and seven years after that, a “Notice of Disposal in Tax Lien Case” executed by the Land Court was recorded in the registry of deeds, noting that there had been entered in the Land Court a decree foreclosing and barring rights of redemption by the prior owners to the lot. That was enough for the Court to rule that “at all material times the city… to the extent permitted by that chapter, engaged in the operation, maintenance, control, and sale of tax title property

The City said its taking of the property pursuant to vested title, subject only to the right of the owners to redeem the property by paying the taxes, is really more in the nature of security until the right of redemption was foreclosed. In other words, the City complained it did not have absolute title, but rather would have been able to keep only the amount of its lien in the event of a taking by eminent domain. Before the right of redemption was foreclosed, the City said, it could not have collected any rents.

The City said its taking of the property pursuant to vested title, subject only to the right of the owners to redeem the property by paying the taxes, is really more in the nature of security until the right of redemption was foreclosed. In other words, the City complained it did not have absolute title, but rather would have been able to keep only the amount of its lien in the event of a taking by eminent domain. Before the right of redemption was foreclosed, the City said, it could not have collected any rents.

Harry, on the other hand, argued that G. L. c. 60, § 54 grants the City the right to possession as soon as a tax title is issued, as opposed to another statute not letting a private buyer from getting possession for two years after buying at a sale.

The Court said that dispute was irrelevant because the City acquired a tax title nine years before the branch fell so even if the two-year period applied, it had long since passed. “In any event,” the Court said, “the city’s right to possession long preceded the date of injury.”

The City, however, contended that held the property in its “governmental capacity” rather than in its “proprietary capacity.” The collection of taxes is a governmental function, the City argued, and it is not liable for the tortious acts of its officers in fulfilling a governmental function. The Court made short work of that argument. The City was maintaining a nuisance on the vacant lot, the Court ruled and “there is no such immunity, however, where there is a nuisance maintained on real estate owned or controlled by a municipality, and this principle obtains ‘even where the nuisance arises out of the performance by the municipality of a governmental duty in the interests of the general public’.”

The liability of a municipality as the owner of land for a private nuisance on the land is no different than the liability of a natural person, the Court said. Trees can be a nuisance as much as a dilapidated building. “As the limb did not overhang the plaintiff’s land,” the Court said, “we have no occasion to examine the question whether the plaintiff is limited to self-help as in Michalson v. Nutting.” What’s more, the Court said, no one has argued that there should be a distinction between trees naturally on land and those that have been planted, “even assuming it is possible to ascertain the origin of this particular tree.”

The liability of a municipality as the owner of land for a private nuisance on the land is no different than the liability of a natural person, the Court said. Trees can be a nuisance as much as a dilapidated building. “As the limb did not overhang the plaintiff’s land,” the Court said, “we have no occasion to examine the question whether the plaintiff is limited to self-help as in Michalson v. Nutting.” What’s more, the Court said, no one has argued that there should be a distinction between trees naturally on land and those that have been planted, “even assuming it is possible to ascertain the origin of this particular tree.”

The Court held that the evidence showed that there was, as early as 1956, when the tree died, a private nuisance to Harry and his property. While not a public shade tree, the elm was on land owned by and subject to the control of the city. It was obviously decayed. A nuisance came into existence while the City was in control of the land. “Public policy in a civilized community requires that there be someone to be held responsible for a private nuisance on each piece of real estate, and, particularly in an urban area, that there be no oases of nonliability where a private nuisance may be maintained with impunity.”

– Tom Root