ENCROACHMENT OF BRANCHES AND ROOT SYSTEMS

It seems like it’s all happening in North Dakota these days. It’s the No. 2 oil producer in the country, unemployment there is at a measly 2.6%, 18,000 more people moved there in 2013 than left … and the state’s got so much natural gas that it’s flaring $100 million in natural gas a month that it can’t use.

The natural resources we care about around here, however, are only underground to the extent of their root systems. Root systems that – along with branches – can occasionally encroach on the neighbors. And that can be a real pain in the neck.

Dr. Richard Herring knows something about pains in the neck. They’re his livelihood as long as they’re found in his patients. But this chiropractor had to deal with another pain the neck, too. The property next door, on which sat an apartment building, had a large tree with branches that were overhanging Dr. Herring’s bone-crunching office. He fought back with self-help, trimming branches, cleaning up the debris that clogged his gutters, and raking up the mess the tree made every fall. But he couldn’t keep ahead. Finally, the branches damaged his building, and the debris created an ice dam on his roof that flooded the place.

The absentee owners and hired managers at the apartment house next refused his entreaties to care for the tree. So he sued, claiming that they had a duty to manage the tree so it didn’t mess up his place. The trial court threw the suit out, telling the good doctor that he could trim the parts of the tree that were overhanging his place, but that was his only remedy.

The absentee owners and hired managers at the apartment house next refused his entreaties to care for the tree. So he sued, claiming that they had a duty to manage the tree so it didn’t mess up his place. The trial court threw the suit out, telling the good doctor that he could trim the parts of the tree that were overhanging his place, but that was his only remedy.

“Wait,” you say, “that’s the Massachusetts Rule.” Right you are. But, as the North Dakota Supreme Court decided, there are other rules out there as well, including some that it thinks are a whole lot better than the doddering relic from Michalson v. Nutting. It reversed the trial court, holding that a tree owner does indeed have a duty to care for his or her trees so as to avoid damage to others.

In its thoughtful opinion, the Court wrote perhaps as fine a roundup on tree encroachment rules as has yet been written.

Herring v. Lisbon Partners Credit Fund, Ltd., 2012 N.D. 226, 823 N.W.2d 493 (Sup.Ct. N.D., 2012). Dr. Herring owned a commercial building in Lisbon housing his chiropractic practice. The apartment building next door is owned by Lisbon Partners and managed by Five Star. Branches from a large tree located on Lisbon Partners’ property overhang Herring’s property and brush against his building. For many years, Dr. Herring trimmed back the branches and cleaned out the leaves, twigs, and debris that would fall from the branches and clog his downspouts and gutters. He claimed that the encroaching branches caused water and ice dams to build up on his roof, and eventually caused water damage to the roof, walls, and fascia of his building. Herring contends that, after he had the damages repaired, he requested compensation from Lisbon Partners and Five Star but they denied responsibility for the damages.

Dr. Herring sued Lisbon Partners and Five Star for the cost to repair his building, claiming the companies had committed civil trespass and negligence, and maintained a nuisance by breaching their duty to maintain and trim the tree so that it did not cause damage to his property. The district court granted Lisbon Partners and Five Star’s motion for summary judgment, dismissing Herring’s claims. The court held Lisbon Partners and Five Star had no duty to trim or maintain the tree, and Herring’s remedy was limited to self-help. He could trim the branches back to the property line at his own expense, but that was it.

Held: The trial court’s dismissal was reversed, and Dr. Herring was given his day in court.

The North Dakota Supreme Court began its analysis by observing that the Massachusetts Rule was the original common law on tree law in the United States, holding that a landowner has no liability to neighboring landowners for damages caused by encroachment of branches or roots from his trees, and the neighboring landowner’s sole remedy is self-help: the injured neighbor may cut the intruding branches or roots back to the property line at his own expense. The basis for the Massachusetts Rule is that it is “wiser to leave the individual to protect himself, if harm results to him from the exercise of another’s right to use his own property in a reasonable way, than to subject that other to the annoyance and burden of lawsuits, which would likely be both countless and, in many instances, purely vexatious.

The Hawaii Rule, on the other hand, rejected the Massachusetts approach as overly simplistic. Instead, it held that the owner of a tree may be liable when encroaching branches or roots cause harm, or create imminent danger of causing harm, beyond merely casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers, or fruit. When overhanging branches or protruding roots actually cause, or there is imminent danger of them causing, sensible harm to property other than plant life, in ways other than by casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers, or fruit, the damaged or imminently endangered neighbor may require the owner of the tree to pay for the damages and to cut back the endangering branches or roots and, if such is not done within a reasonable time, the damaged or imminently endangered neighbor may cause the cutback to be done at the tree owner’s expense.

The Restatement Rule, based upon the Restatement (Second) of Torts §§ 839-840 (1979), distinguishes between natural and artificial conditions on the land. Under the Restatement Rule, if the tree was planted or artificially maintained it may be considered a nuisance and its owner may be liable for resulting damages, but there is no liability for a naturally growing tree that encroaches upon neighboring property.

The Virginia Rule, adopted in 1939, makes a distinction between noxious and non-noxious trees. Under the old Virginia rule, a tree encroaching upon neighboring property will be considered a nuisance, and an action for damages can be brought, if it is a “noxious” tree and has inflicted a “sensible injury.”

The district court concluded that under N.D.C.C. § 47-01-12, Herring had a “right” to do as he wished with the overhanging branches and underlying roots of the tree, and therefore this portion of the tree was “just as much the responsibility of the adjacent landowner as it is the owner of the trunk.” In effect, the district court concluded that because Herring had the “right” to the branches above his property, he therefore had the responsibility to maintain them as well.

The state Supreme Court complained that the district court had essentially nullified N.D.C.C. § 47-01-17. That statute expressly provides that when the trunk of the tree is wholly upon the land of one owner, the tree “belong[s] exclusively to that owner.” The district court’s holding that Herring in effect owned the branches above his property was thus contrary to statute. Statutes must be construed as a whole and harmonized to give meaning to related statutes, and are to be interpreted in context to give meaning and effect to every word, phrase, and sentence. The interpretation adopted by the district court did not give meaning and effect to that portion of N.D.C.C. § 47-01-17 which provides that the owner of the tree’s trunk “exclusively” owns the entire tree.

Contrary to the district court’s conclusion that the Massachusetts Rule was more consistent with North Dakota statutory law, the Supreme Court held that the Hawaii Rule more fully gives effect to both statutory provisions. The Hawaii Rule is expressly based upon the concept, embodied in N.D.C.C. § 47-01-17, that the owner of the trunk of a tree which is encroaching on neighboring property owns the entire tree, including the intruding branches and roots. And because the owner of the tree’s trunk is the owner of the tree, the Supreme Court thought he or she should bear some responsibility for the rest of the tree. The Court said “we think he is duty bound to take action to remove the danger before damage or further damage occurs.”

The Supreme Court also observed that “the Hawaii Rule is the most well-reasoned, fair, and practical of the four generally recognized rules. We first note that the Restatement and Virginia rules have each been adopted in very few jurisdictions, and have been widely criticized as being based upon arbitrary distinctions which are unworkable, vague, and difficult to apply … In fact, the Supreme Court of Virginia has … abandoned the [old] Virginia rule in favor of the Hawaii Rule [in] Fancher …”

The Court also complained that the Massachusetts Rule has been widely criticized as being “unsuited to modern urban and suburban life.” The Massachusetts Rule fosters a “law of the jungle” mentality, the Court said, because self-help effectively replaces the law of orderly judicial process as the only way to adjust the rights and responsibilities of disputing neighbors. The Court observed that while self-help may be sufficient “when a few branches have crossed the property line and can be easily pruned by the neighboring landowner himself, it is a woefully inadequate remedy when overhanging branches break windows, damage siding, or knock holes in a roof, or when invading roots clog sewer systems, damage retaining walls, or crumble a home’s foundation.”

Accordingly, the North Dakota Supreme Court held that “encroaching trees and plants are not nuisances merely because they cast shade, drop leaves, flowers, or fruit, or just because they happen to encroach upon adjoining property either above or below the ground. However, encroaching trees and plants may be regarded as a nuisance when they cause actual harm or pose an imminent danger of actual harm to adjoining property. If so, the owner of the tree or plant may be held responsible for harm caused by it, and may also be required to cut back the encroaching branches or roots, assuming the encroaching vegetation constitutes a nuisance.” The rule does not prevent a landowner, at his or her own expense, from cutting away the encroaching vegetation to the property line whether or not the encroaching vegetation constitutes a nuisance or is otherwise causing harm or possible harm to the adjoining property.

ENCROACHMENT, MASSACHUSETTS STYLE

Encroachment … not the neutral-zone penalty that will cost the defense five yards. Rather , encroachment is what happens when your neighbor’s tree roots break into your sewer system, when leaves and nuts are dumped into your gutters, or when the branches rain down on your car or lawn. The law that governs rights and responsibilities when a neighbor’s tree encroaches on your property in only about 80 years old. Before that time, a simpler time perhaps, people didn’t resort to the courts quite so much.

, encroachment is what happens when your neighbor’s tree roots break into your sewer system, when leaves and nuts are dumped into your gutters, or when the branches rain down on your car or lawn. The law that governs rights and responsibilities when a neighbor’s tree encroaches on your property in only about 80 years old. Before that time, a simpler time perhaps, people didn’t resort to the courts quite so much.

The “Massachusetts Rule” you see referenced so often in tree encroachment matters arose in Michalson v. Nutting, 275 Mass. 232, 175 N.E. 490, 76 A.L.R. 1109 (Sup.Jud.Ct. Mass. 1931). This is the grand-daddy of encroachment cases, the adoption of what has become known the self-help mantra of neighbors everywhere. In Michalson, roots from a poplar growing on the Nuttings’ land had penetrated and and damaged sewer and drain pipes at Michalson’s place. As well, the roots had grown under Michalson’s concrete cellar, causing cracking and threatening serious injury to the foundation. Michalson wanted the Nuttings to cut down the tree and remove the roots. They said “Nutting doing.”

Michalson sued, asking for a permanent injunction restraining the Nuttings from allowing the roots to encroach on the his land. Oh, and Michalson wanted money, too. The trial judge found the Nuttings were not liable just because their tree was growing. He threw Michalson’s lawsuit out, and Michalson appealed.

Held: In what has become known as the “Massachusetts Rule,” the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts held that a property owner’s remedies are limited to “self help.” In other words, a suffering property owner may cut off boughs and roots of neighbor’s trees which intrude into another person’s land. But the law will not permit a plaintiff to recover damages for invasion of his property by roots of trees belonging to adjoining landowner. And a plaintiff cannot obtain equitable relief — that is, an injunction — to compel an adjoining landowner to remove roots of tree invading plaintiff’s property or to restrain such encroachment.

BOOK HIM, DANNO, ‘TREE NEGLIGENCE’ ONE

The law of encroaching overhanging trees runs a continuum from total self-help (the “Massachusetts Rule”) – as we discussed yesterday – to tree owner liability (the “Hawaii Rule”) with several different flavors in between.

In Whitesell v. Houlton, 632 P.2d 1077 (App. Ct. 1981), a Hawaiian appellate court first adopted what is generally known as the “Hawaii Rule,” which held that when there is imminent danger of overhanging branches causing “sensible” harm to property other than plant life, the tree owner is liable for the cost of trimming the branches as well as for the damage caused.

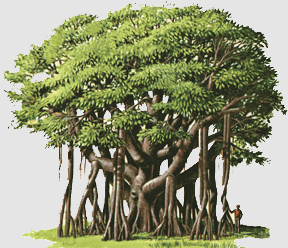

Maybe the court’s holding that the Whitesell v. Houlton tree was a nuisance arose from the hard facts of the case: the tree was a massive banyan tree, with a 12-foot trunk and 90 foot height. Perhaps it was the political and cultural nature of the Islands is far removed from the flintier New Englanders and the type of self-reliance embraced by the “Massachusetts Rule.” For whatever reason,  if a branch from a healthy tree in Massachusetts is in danger of falling into a neighbor’s yard, he may trim it at his own expense … but that’s it. In Hawaii, overhanging branches or protruding roots constitute a nuisance when they actually cause, or there is imminent danger of them causing, sensible harm to property other than plant life, in ways other than by casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers, or fruit. Then, the damaged or imminently endangered neighbor may require the owner of the offending tree to pay for damages and to cut back endangering branches or roots. If such is not done within a reasonable time, the neighbor may cause the cut-back to be done at tree owner’s expense.

if a branch from a healthy tree in Massachusetts is in danger of falling into a neighbor’s yard, he may trim it at his own expense … but that’s it. In Hawaii, overhanging branches or protruding roots constitute a nuisance when they actually cause, or there is imminent danger of them causing, sensible harm to property other than plant life, in ways other than by casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers, or fruit. Then, the damaged or imminently endangered neighbor may require the owner of the offending tree to pay for damages and to cut back endangering branches or roots. If such is not done within a reasonable time, the neighbor may cause the cut-back to be done at tree owner’s expense.

Nothing in this ruling prevents a landowner — at his own expense — from cutting any part of an adjoining owner’s trees or other plant life up to his property.

Whitesell v. Houlton, 632 P.2d 1077 (App. Ct. 1981). The Whitesells and Mr. Houlton lived next to each other. Mr. Houlton owned a 90-foot tall banyan tree with foliage extending 100 to 110 feet from the trunk. The tree overhung the Whitesells’ property. and the two-lane street fronting both properties. The Whitesells asked Mr. Houlton repeatedly over a two-year period to trim the tree, and they took it upon themselves to do so at various times. Their VW microbus was damaged by low-hanging branches, their garage roof was damaged by some intruding branches from the tree, and they identified branches damaged in a storm that were in danger of falling.

Despite their entreaties, Mr. Houlton did nothing. Finally, the Whitesells hired a professional tree trimmer who cut the banyan’s branches back to Houlton’s property line, and then sued Mr. Houlton to get him to pay.

The trial court sided with the Whitesells, and ruled that Mr. Houlton had to pay. He appealed.

Held: Mr. Houlton had to pay. The court surveyed different approaches taken by other states, identifying the “Massachusetts Rule” holding that Mr. Houlton had no duty to the Whitesells, or the “Virginia Rule” that said Mr. Houlton had a duty to prevent his tree from causing sensible damage to his neighbor’s property.

The Court agreed with Mr. Houlton that “the Massachusetts rule is ‘simple and certain’. However, we question whether it is realistic and fair. Because the owner of the tree’s trunk is the owner of the tree, we think he bears some responsibility for the rest of the tree. It has long been the rule in Hawaii that if the owner knows or should know that his tree constitutes a danger, he is liable if it causes personal injury or property damage on or off of his property . . . Such being the case, we think he is duty bound to take action to remove the danger before damage or further damage occurs.” This is especially so, the Court said, where the tree in question was a banyan tree in the tropics.

Thus, the Court adopted what it called “a modified Virginia rule.” It held that “overhanging branches which merely cast shade or drop leaves, flowers, or fruit are not nuisances; that roots which interfere only with other plant life are not nuisances; that overhanging branches or protruding roots constitute a nuisance only when they actually cause, or there is imminent danger of them causing, sensible harm to property other than plant life, in ways other than by casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers, or fruit; that when overhanging branches or protruding roots actually cause, or there is imminent danger of them causing, sensible harm to property other than plant life, in ways other than by casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers, or fruit, the damaged or imminently endangered neighbor may require the owner of the tree to pay for the damages and to cut back the endangering branches or roots and, if such is not done within a reasonable time, the damaged or imminently endangered neighbor may cause the cutback to be done at the tree owner’s expense.”

The Court pointed out that this rule did not strip a landowner of the right, at his or her expense, to trim a neighbor’s overhanging tree or subterranean tree roots up to the property line.

VIRGINIA ABANDONS “NOXIOUS” TREE STANDARD

Encroachment: Not the football kind, but the tree kind. Encroachment governs the rights of adjoining property owners when the trees on one of the properties encroaches on the property of the other. Overhanging branches, invasive root systems, falling debris … those kinds of problems. For years, there have been two different approaches to encroachment under American law. On one end of the continent, New England adopted the “Massachusetts Rule,” that landowners are limited to self-help – but not lawsuits – to stop encroaching trees and roots. And at the other end of these 50 United States was the “Hawaii Rule,” a holding that a landowner could sue for damages and injunctive relief when a neighbor’s tree was causing actual harm or was an imminent danger to his or her property.

Between the two competing rules, Virginia found itself firmly straddling the line. The fair Commonwealth may be for lovers, but it was also for temporizers. The landmark Old Dominion case on the issue, Smith v. Holt, held that the Massachusetts Rule applied unless the tree in question was (1) causing actual harm or was an imminent danger; and (2) “noxious.” This holding brings to mind the maxim “a camel looks like a horse designed by a committee.” Frankly, Smith v. Holt had “committee’ written all over it. It seemed to hold that the Massachusetts Rule applied except where it didn’t. And what did “noxious” have to do with anything?

The Virginia Supreme Court finally addressed the confusing situation several years ago, in a case that bears our review. In Fancher v. Fagella, the Court found itself heist on the “noxious” petard. Everyone could agree that poison ivy was noxious, and most people could agree kudzu was noxious. But how about a cute little shade tree? Shade trees are definitely not in the same league with poisonous or entangling pests, but yet, a cute little shade tree can come out of the ground harder and do more damage than poison ivy or kudzu ever could.

Take the tree in Fancher. It was a sweet gum, a favored landscaping tree as well as a valuable hardwood. But for poor Mr. Fancher, it was Hydra covered in bark. Only halfway grown, Fagella’s sweet gum’s roots were already knocking over a retaining wall, kicking up patio stones, breaking up a house foundation and growing into sewers and even the house electrical system. Fancher sued for an injunction, but the trial court felt obligated to follow Smith v. Holt. There was just no way that a sweet gum tree could be noxious, the local court held, and thus, it would not help the frustrated Mr. Fancher. But the Virginia Supreme Court, wisely seeing that the “noxious” standard was of no help in these cases, abandoned the hybrid rule of Smith v. Holt., an unwieldy compromise that had already become known as the “Virginia Rule.” The Court – noting that the “Massachusetts Rule” was a relic of a more rural, bucolic age – decided that the “Hawaii Rule” was the best fit for modern, crowded, helter-skelter suburban life. It sent the case back to the trial court, instructing the judge that the court should consider whether an injunction should issue.

The case:

Fancher v. Fagella, 650 S.E.2d 519, 274 Va. 549 (2007). Fancher and Fagella were the owners of adjoining townhouses in Fairfax County, Virginia (a largely urban or suburban county west of Washington, D.C., and part of the Washington metropolitan area). Fagella’s property is higher in elevation than Fancher’s, and a masonry retaining wall runs along the property line to support the grade separation. Fancher has a sunken patio behind his home, covered by masonry pavers.

Fagella had a sweet gum tree located a few feet from the retaining wall, about 60 feet high with a 2-foot diameter trunk at its base. Sweet gums are native to the area, and grow to 120 to 140 feet in height at maturity, with a trunk diameter of 4 to 6 feet. The tree was deciduous, dropping spiky gumballs and having a heavy pollen load. It also has an invasive root system and a high demand for water.

Fagella had a sweet gum tree located a few feet from the retaining wall, about 60 feet high with a 2-foot diameter trunk at its base. Sweet gums are native to the area, and grow to 120 to 140 feet in height at maturity, with a trunk diameter of 4 to 6 feet. The tree was deciduous, dropping spiky gumballs and having a heavy pollen load. It also has an invasive root system and a high demand for water.

In the case of Fagella’s tree, the root system had displaced the retaining wall between the properties, displaced the pavers on Fancher’s patio, caused blockage of his sewer and water pipes and had begun to buckle the foundation of his house. The tree’s overhanging branches grew onto his roof, depositing leaves and other debris in his rain gutters. Fancher attempted self-help, trying to repair the damage to the retaining wall and the rear foundation himself, and cutting back the overhanging branches, but he was ineffective in the face of continuing expansion of the root system and branches. Fancher’s arborist believed the sweet gum tree was only at mid-maturity, that it would continue to grow, and that “[n]o amount of concrete would hold the root system back.” The arborist labeled the tree “noxious” because of its location, and said that the only way to stop the continuing damage being done by the root system was to remove the tree entirely.

Fancher sued for an injunction compelling Fagella to remove the tree and its invading root system entirely, and asked for damages to cover the cost of restoring the property to its former condition. Fagella moved to strike the prayer for injunctive relief. The trial court, relying on Virginia law set down in Smith v. Holt, denied injunctive relief. Fancher appealed.

Fancher sued for an injunction compelling Fagella to remove the tree and its invading root system entirely, and asked for damages to cover the cost of restoring the property to its former condition. Fagella moved to strike the prayer for injunctive relief. The trial court, relying on Virginia law set down in Smith v. Holt, denied injunctive relief. Fancher appealed.

Held: The Supreme Court abandoned the “Virginia Rule,” adopting instead the “Hawaii Rule” that while trees and plants are ordinarily not nuisances, they can become so when they cause actual harm or pose an imminent danger of actual harm to adjoining property. Then, injunctive relief and damages will lie. The Court traced the history of the encroachment rule from the “Massachussetts Rule” — which holds that a landowner’s right to protect his property from the encroaching boughs and roots of a neighbor’s tree is limited to self-help, i.e., cutting off the branches and roots at the point they invade his property — through the modern “Hawaii Rule.” The Court noted that Virginia had tried to strike a compromise between the two positions with the “Virginia Rule” set out in Smith v. Holt, which held that the intrusion of roots and branches from a neighbor’s plantings which were “not noxious in [their] nature” and had caused no “sensible injury” were not actionable at law, the plaintiff being limited to his right of self-help.

The Court found the “Massachusetts Rule” rather unsuited to modern urban and suburban life, although it may still work well in many rural conditions. It admitted that the “Virginia Rule” was justly criticized because the classification of a plant as “noxious” depends upon the viewpoint of the beholder. Just about everyone would agree that poison ivy is noxious. Many would agree that kudzu is, too, because of its tendency toward rampant growth, smothering other vegetation. But few would declare healthy shade trees to be noxious, although they may cause more damage and be more expensive to remove, than the poison ivy or kudzu. The Court decided that continued reliance on the distinction between plants that are noxious, and those that are not, imposed an unworkable and futile standard for determining the rights of neighboring landowners.

Therefore, the Court overruled Smith v. Holt, insofar as it conditions a right of action upon the “noxious” nature of a plant that sends forth invading roots or branches into a neighbor’s property. Instead, it adopted the Hawaii Rule, finding that encroaching trees and plants are not nuisances merely because they cast shade, drop leaves, flowers, or fruit, or just because they happen to encroach upon adjoining property either above or below the ground. However, encroaching trees and plants may be regarded as a nuisance when they cause actual harm or pose an imminent danger of actual harm to adjoining property. If so, the owner of the tree or plant may be held responsible for harm caused to adjoining property, and may also be required to cut back the encroaching branches or roots, assuming the encroaching vegetation constitutes a nuisance. The Court was careful to note that it wasn’t altering existing law that the adjoining landowner may, at his own expense, cut away the encroaching vegetation to the property line whether or not the encroaching vegetation constitutes a nuisance or is otherwise causing harm or possible harm to the adjoining property.

The Court warned that not every case of nuisance or continuing trespass may be enjoined, but it could be considered here. The decision whether to grant an injunction, the Court held, always rests in the sound discretion of the chancellor and depends on the relative benefit an injunction would confer upon the plaintiff in contrast to the injury it would impose on the defendant. In weighing the equities in a case of this kind, the chancellor must necessarily first consider whether the conditions existing on the adjoining lands are such that it is reasonable to impose a duty on the owner of a tree to protect a neighbor’s land from damage caused by its intruding branches and roots. In the absence of such a duty, the traditional right of self-help is an adequate remedy. It would be clearly unreasonable to impose such a duty upon the owner of historically forested or agricultural land, but entirely appropriate to do so in the case of parties, like those in the present case, who dwell on adjoining residential lots.

HAWAIIAN, NEW MEXICO STYLE

Long before the Virginia Supreme Court’s decision in Fancher v. Fagella, a little-noticed New Mexico decision grappled with the problems caused by cottonwood trees. They can be majestic, and they were welcome enough to the pioneers that the cottonwood is the state tree of Kansas. But at the same time, there are those who label them as dangerous, messy and a tree that should “be removed from most residential property.”

Mr. Fox had a cottonwood tree he loved dearly. His neighbors didn’t fall into the same category, however. They hated the messy tree with the invasive and prolific root system. Like the banyan tree in Whitesell v. Houlton, there was a lot about Mr. Fox’s cottonwood not to like.

A time-honored legal maxim is that “hard cases make bad law.” That may have accounted for the trial court decision against Mr. Fox, but more level-headed weighing of the competing property and societal interests occurred in the Court of Appeals.

Abbinett v. Fox, 103 N.M. 80, 703 P.2d 177 (Ct.App. N.M. 1985). The Abbinetts and Fox formerly owned adjoining residences in Albuquerque. The Abbinetts sued, alleging that while Fox owned his place, roots from a large cottonwood tree on his property encroached onto their land and damaged a patio slab, cracked the sides of a swimming pool, broke a block wall and a portion of the foundation of their house, and clogged a sprinkler system.

The Abbinetts asked for an injunction against Fox. The trial court found against Fox for $2,500, but denied injunctive relief to force Fox to remove the tree roots. Instead, the Court entered an order authorizing the Abbinetts to utilize self-help to destroy or block the roots of the cottonwood trees from encroaching on their land. Plaintiff appealed.

Held: The New Mexico Court of Appeals grappled for the first time with the Massachusetts Rule, the Hawaii Rule and the Smith v. Holt-era Virginia Rule. Instead of adopting any one of them, the Court cobbled together a hybrid of all three, finding that when overhanging branches or protruding roots of plants actually cause – or there is imminent danger of them causing – “sensible harm” to property other than plant life, the damaged or endangered neighbor may require owner of the tree to pay for damages and to cut back the endangering branches or roots. Such “sensible harm” has to be something more than merely casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers or fruit. In so doing, the New Mexico Court anticipated the Virginia Supreme Court’s Fancher v. Fagella holding by about 22 years.

The New Mexico Court also held that it is duty of a landowner to use his property in a reasonable manner so as not to cause injury to adjoining property. This is the Hawaii Rule. And the landowner who suffers encroachment from the tree of another may — but is not required to — “abate it without resort to legal proceedings provided he can do so without causing breach of peace.” This, of course, is the heart of the Massachusetts Rule. The New Mexico Court called all of these holdings a “modified Virginia Rule,” as indeed it was.

The Court held that a trial court may grant both damages for already incurred injuries and injunctive relief to prevent future harm, where there is showing of irreparable injury for which there is no adequate remedy at law.

I have read this and shown it to my neighbor as well as the City Attorney who has threatened to fine us if we trim encroaching branches. I live in Illinois and was told by them that your article means nothing. My neighbor has a large Oak Tree that has several branches encroaching over 35 feet onto my property. I wanted them trimmed away because of their size and height and am worried that one day with the heavy snows that one might fall on my children. The response from the city forester was “do not have your kids play under it if you are that concerned.” Anyway, after getting ready to sue the city for the right to do this, they then said they will not get involved between neighbor to neighbor dispute and that I do have a right to trim branches that are encroaching as long as i follow the Arbrocultural standards. I talk to the neighbor again who refuses to let us go on her property to trim branches according to these standards (cut to trunk of tree). My arborist then calls the city to tell them that the neighbor will not allow us on her property and thus we will hire a lift and cut them from my side. The city forester then stated that if we cut the branches and they are not done by the standard they requested, they will FINE me 400 dollars per inch Diameter of Tree (its about 36 inches) thus a fine of about 15 Thousand dollars. My arborist then asks the city what can we do, since we have the right to trim to property line, but you set these standards which then make it illegal to do so unless we trim to the tree trunk…but without her permission, we can not do it…the city said that is our problem. What can I do besides going to court and if I take this to court can I win?

Use the pollarding standard from ANSI – you have to trim more frequently, but it would solve your problem.

We are NOT allowed on her property to cut any branches so this method will not work. Also the City does NOT want this Tree trimmed “down” at all since they told us that this can potentially KILL the tree. Their response was that we are allowed to cut the branches that overhand onto our property BUT only if we cut that Branch to the TRUNK of the tree, otherwise we will be fined 15 Thousand dollars AND put an escrow for three years and then the forester will come out to see if the tree is “damaged” in any way. Since we are not allowed to go onto her property, we essentially can not trim this branch. Sorry but your response does not solve the problem since we do not have access to her property.

You can pollard any branch at any point of it, I would say that as long as it gets some sunlight, and if you find a small live twig, you should be able to have a good pollard head. You would not have to pollard the entire tree. Of course, then you will also have a non-symmetrical tree, but that’s not your problem. Have you approached the city forester with the ANSI booklet regarding pollarding? I would think that as long as you attempted to do it with due diligence, they cannot hold it against you.

Another thing, if you can get a lift to the property line to get the branch cut, you would not have to enter her property, anymore than the tree is entering your property. Depending on the size of the branch it may be fairly easy to remove small sections and drop them back on your property. If the branch is more than 16-18″ at base, this might not work, since it will be far too heavy. This approach would be expensive since it would take a long time to complete.

Another thing to think about, is there a branch that is approximately a third of the diameter of the main branch near your property line? If there is, you can trim to that, you do not have to bring it back all the way to the trunk.

Why is trimming this tree such an issue? Is it a historic or rare specimen tree? Does your neighbor have political influence?

Hi Artem,

We have hired an arborist to rent a lift and cut the tree branches this November. I really do not have an answer for you on why our city forester was such a jerk. I can tell you that he no longer works there nor does the City Attorney who told me that I can sue and most likely win, but do I want to spend 30K just to cut a few tree branches.

That said, I have hired an attorney and will cut the branches overhanging our property. I was assured by my attorney that not only is this COMMON law that you have a right to protect your family and property by any branch overhanging your property, but that the judge will most likely force the city to pay my attorney fees if this does go to court.

The silly thing is that EVERY tree that has a diameter of more then 4 inches is considered a “protected” tree in our city. But because this neighbor will not let us prune correctly because she is not allowing us on her property, the burden of the tree’s health and not being cut according to standards falls on her. What really is upsetting is that certain people believe that their rights supersede everyone else’s. I offered to pay to trim her whole tree, I offered to pay to fertilize it as well to make sure it becomes healthy because it is not so healthy right now. But to no avail. So I am tired of waiting for a miracle to happen while branches fall off this mammoth tree and just hope that it does not hit any of little children as they play in the backyard during the winter.

Will let you all know how it turns out

Ever since I found this blog- 12 hours ago I have been reading constantly. Great great stuff. Thank you so much. (ISA Certified Arborist City of Reno Urban Forestry Commissioner)

Still does not answer my question. My neighbor has an apple tree which branches have grown over my property where I mow causing scratches and scrapes to my person while mowing. The branches are now extending into my lane causing scratches to vehicles. Is it legal for me to trim the branches back to his property line or does he have to be the one to do that, and what if he refuses. (He is a jerk of a neighbor so i expect him to refuse, he is friends with no neighbor around here, nobody likes the people because they are so hateful) I don’t wish to cause him to lose any yield from the tree branches this year but they are now tearing up me and my car. THEY NEED CUT BACK.

I wrote our neighbor whose mango tree branches are encroaching far beyond the property line to trim dopwn the btanches so dead leaves all over our front yard will be at a minimum. He approached my help who was cleaning up the front yard that the Massachussetts law applies. Which office in the Honolulu City & County can I seek help to explain to them the Hawaii law on taking responsibility to hire a tree cutter for trimming down the branches that has encroached property line.