A RATHER SURPRISING HOLDING FROM A DELAWARE TRIAL COURT

In this tree law gig, I read a lot of cases. After a while, reading between the lines gets a lot easier.

Today’s case, which I decided was nothing special, was just about some neighbors who were over-the-top haters of the defendant. The defendant seems like a guy whose crime was that he apparently had the effrontery to move in next door and then fix up the place.

Today’s case, which I decided was nothing special, was just about some neighbors who were over-the-top haters of the defendant. The defendant seems like a guy whose crime was that he apparently had the effrontery to move in next door and then fix up the place.

The trial court’s long opinion had flushed away most of the plaintiffs’ breathless and frantic complaint – and “flushed” is the correct verb for most of the claims the tin-foil-hatted neighbors made against the defendant– when I got to their claim that defendant Bill Collison had “damaged a maple tree near the property line by shaving the trees directly up from the property line.”

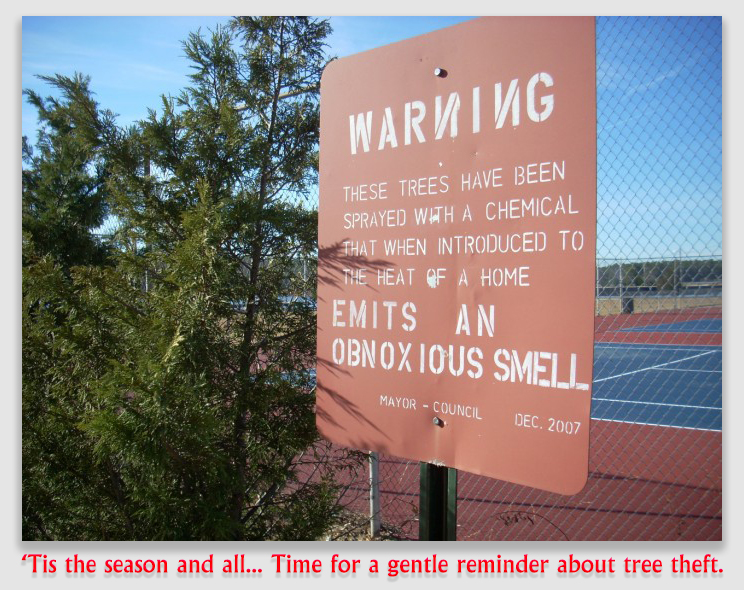

“Holy Massachusetts Rule!” I muttered to myself. Everyone knows that this claim should be summarily tossed, because the Massachusetts Rule is as universally accepted as is turkey at Thanksgiving. Assuming Bill did “shave” the tree at the property line, that’s perfectly within his rights.

Much to my shock, the Court disagreed. It held that the right of “self-help” trimming of encroaching branches is not established in Delaware, and if this court was going to do it, it would not do it on summary judgment. It became obvious to me that whatever else Judge Calvin Scott, Jr., of Newark, Delaware, reads with his morning coffee, it sure isn’t this blog.

It did not take long to find reason to question the Judge’s refusal to grant summary judgment on this issue. In the 1978 Delaware Chancery Court decision Etter v. Marone, the court ruled

At the same time, certain generally accepted principles obtain with regard to encroaching trees or hedges. Regardless of whether encroaching branches or roots constitute a nuisance, a landowner has an absolute right to remove them so long as he does not exceed or go beyond his boundary line in the process. 2 C.J.S. 51, Adjoining Landowners § 52; 1 Am.Jur.2d 775, Adjoining Landowners § 127. He may not go beyond the line and cut or destroy the whole or parts of the plant entirely on another’s land even though the growth may cause him personal inconvenience or discomfort. 2 C.J.S. 51, supra.

So the Judge seems to be wrong: Delaware is firmly in the Massachusetts Rule camp.

What with allegations of underground tanks, clogged drainpipes and extreme mental anguish contained in the messy and unsupported complaint, Judge Scott pretty clearly had his hands full. By and large, he acquitted himself masterfully in the opinion, carefully deconstructing the plaintiffs’ complaints. But I’m betting that in about nine weeks, the Judge will be sitting down to a turkey dinner with all the trimmings. When he does, he should reflect that as many of us accept the Massachusetts Rule as will be dining on the same meal that day.

Dayton v. Collison, C.A. No. N17C-08-100 CLS (Super. Ct. Del. Sept. 24, 2019), 2019 Del. Super. LEXIS 446. Margaret Dayton and Everett Jones clearly had it out for their neighbor, Bill Collison. They claimed that since 2014, Bill had removed a significant number of standing trees and about 5,000 square feet of naturally growing plants from the City of Newark’s natural buffer zone, removed a 30-year-old drainage pipe located on his property and filled the remaining pipe with rocks and debris, intentionally altered the natural grade of his property so as to interfere with the natural flow of water, and trimmed a maple tree located on Maggie and Ev’s property along the boundary line. Additionally, they claim that an underground storage tank Bill installed – apparently your garden-variety propane tank – violates Newark’s municipal ordinances.

Dayton v. Collison, C.A. No. N17C-08-100 CLS (Super. Ct. Del. Sept. 24, 2019), 2019 Del. Super. LEXIS 446. Margaret Dayton and Everett Jones clearly had it out for their neighbor, Bill Collison. They claimed that since 2014, Bill had removed a significant number of standing trees and about 5,000 square feet of naturally growing plants from the City of Newark’s natural buffer zone, removed a 30-year-old drainage pipe located on his property and filled the remaining pipe with rocks and debris, intentionally altered the natural grade of his property so as to interfere with the natural flow of water, and trimmed a maple tree located on Maggie and Ev’s property along the boundary line. Additionally, they claim that an underground storage tank Bill installed – apparently your garden-variety propane tank – violates Newark’s municipal ordinances.

Maggie and Ev allege Bill’s property is a public nuisance, and that they have suffered “extreme mental anguish and damages of at least a $50,000 loss in the value of their home” because of flooding caused by Bill’s alteration of the grade’ invasion of privacy due to the removal of the buffer zone, being forced to live next to a hazardous condition because of the propane tank, and “damage or potential damage” (guess they’re not sure which) to the structural integrity of their property’s foundation.

They also claim Bill trespassed on their property multiple times to “alter the natural drainage flow of water, construct a berm, cut Plaintiffs’ trees, and take pictures or otherwise spy on Plaintiffs. From this, Plaintiffs claim they have suffered and continue to suffer damages and mental anguish in a sum to be determined at trial.”

Bill moved for summary judgment, claiming that Ev and Maggie cannot bring claims based on the alleged violation of city ordinances, and showing that their claims were baseless.

Held: Summary judgment in Bill’s favor was granted on all claims except the tree-trimming claim.

The Court held that a public nuisance is one which affects the rights to which every citizen is entitled. The activity complained of must produce a tangible injury to neighboring property or persons and must be one that the court considers objectionable under the circumstances.

To have standing to sue on a public nuisance claim, an individual must be capable of recovering damages and (2) have standing to sue as a representative of the public, “as in a citizen’s action or class action.” Here, Maggie and Ev have no right to bring a claim against Bill for alleged violations of the Code and thus, no standing to sue as representatives of the public. The Newark Code creates no rights enforceable by members of the public, and thus, it presents no basis upon which the requested relief may be granted.

To determine whether an implied private right of action exists, Delaware courts ask, among other things, whether there is any indication of legislative intent to create or deny a private remedy for violation of the act. Under the Newark City Charter, the City possesses “all the powers granted to municipal corporations by the Constitution and laws of the State of Delaware, together with all the implied powers necessary to carry into execution all the powers granted..” The city manager is responsible for administering all city affairs authorized by or under the Charter and may appoint individuals to enforce specific ordinances of the Code. The Court held that these reservations showed that the City of Newark intended for it to be solely responsible for enforcing its ordinances and did not intend to create a private right of action based upon ordinance violations.

Claims that Bill’s tree cutting was creating a public nuisance on the floodplain, likewise alleged violation of City ordinances, and thus were claims that Ev and Maggie lacked any standing to bring. As well, their claim that Bill’s propane tank had been installed without a permit alleged a violation of the City Code, a claim only the City could make.

Finally, Ev and Maggie claimed Bill created a public nuisance because he allegedly removed a drainage pipe from his property and filled the remaining pipe with rocks and debris. Outside of the fact that they were able to cite no evidence that any drainpipe had ever existed on Bill’s property, only the City of Newark had jurisdiction and control over drainage.

Finally, Ev and Maggie claimed Bill created a public nuisance because he allegedly removed a drainage pipe from his property and filled the remaining pipe with rocks and debris. Outside of the fact that they were able to cite no evidence that any drainpipe had ever existed on Bill’s property, only the City of Newark had jurisdiction and control over drainage.

But Ev and Maggie claimed that Bill created private nuisances, too. A private nuisance is a nontrespassory invasion of another’s interest in the private use and enjoyment of their land. There are two types of private nuisance recognized in Delaware: nuisance per se and nuisance-in-fact. A claim for nuisance per se exists in three types of cases: 1) intentional, unreasonable interference with the property rights of another; 2) interference resulting from an abnormally hazardous activity conducted on the person’s property; and 3) interference in violation of a statute intended to protect public safety. A claim for nuisance-in-fact exists when the defendant, although acting lawfully on his own property, permits acts or conditions that “become nuisances due to circumstances or location or manner of operation or performance.” Plaintiffs allege claims under both the theory of nuisance per se and the theory of nuisance-in-fact.

But saying it doesn’t make it so. The Court granted Bill’s motion for summary judgment on the private nuisance claims because Ev and Maggie did not provide sufficient evidence supporting their nuisance per se claim, and did not submit expert reports to show the necessary elements of their claims.

Ev and Maggie also argued that Bill’s destruction of certain trees on their property and his failure to respect known boundary lines also constitute a continuing nuisance. They alleged that they suffered a diminution in the value of their home, in an amount of at least $50,000, as a result of the “nuisance created and maintained by” Bill. Ev and Maggie estimated the value of their home and the loss they had suffered. They argue that, as landowners, they may offer an opinion on the value of real estate. The Court disagreed: “Although Plaintiffs might know the fair market value of their property based on what they paid for it and based on a comparison of their property to other homes in the area, Plaintiffs do not know how each of Defendant’s alleged actions changed the value of their property. To establish how each of Defendant’s actions changed the value of Plaintiffs’ property, Plaintiffs would need to identify and submit an expert report from an expert witness; Plaintiffs have not done so.”

Those tin hats really work — it’s just that THEY want you to think there’s something wrong with wearing ’em …

Ev and Maggie allege that they have suffered “extreme mental anguish” as a result of Bill’s alleged nuisances. The Court ruled that Ev and Maggie “needed to show proof of the ‘extreme mental anguish’ they allegedly suffered through a medical expert. Without expert testimony, the Court is not able to find that Plaintiffs suffered this type of harm or that Defendant’s conduct caused such harm. Plaintiffs have neither identified an expert witness to testify to this matter nor submitted an expert report regarding this matter.”

Ev and Maggie’s only victory came on their claim that Bill damaged their maple tree. They alleged that he damaged a maple tree near the property line by shaving the trees directly up from the property line. Ev and Maggie have identified and submitted a report from an arborist, Russell Carlson, detailing the manner in which the maple tree was damaged by Bill’s alleged cutting back of the branches. The report shows the damage done to the maple tree and estimates the cost of that harm.

Bill responded to their report, arguing that he has a right to engage in “self-help” to the property line. The Court held that “it remains unclear in Delaware whether a defendant has a right to engage in ‘self-help’ by cutting tree limbs that extend onto his property. The Court declines to make a determination on this issue in a motion for summary judgment. Therefore, Defendant has not shown, in the face of Mr. Carlson’s report, that he is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Accordingly, summary judgment on this allegation is not proper.”

Ev and Maggie argued they are entitled to treble damages pursuant to 25 Del. C. § 1401, Timber Trespass. The Court may award treble damages for timber trespass when the plaintiff establishes that a trespasser “fells or causes to be cut down or felled a tree or trees growing upon the land of another”; 2) that plaintiff’s property was established and marked by permanent and visible markers or that the trespasser was on notice that the rights of the plaintiff were in jeopardy; and 3) that the trespass was willful.

Because Ev and Maggie only alleged that Bill damaged the tree, and did not cut it down altogether, they are not entitled to treble damages.

Finally, Ev and Maggie alleged that Bill intentionally trespassed on their property. The elements of a claim for intentional trespass are that the plaintiff has lawful possession of the land, the defendant entered onto the plaintiff’s land without consent or privilege, and the plaintiff shows damages. The Court held that there was a factual dispute as to whether Bill ever entered Ev’s and Maggie’s land. Thus, Bill was denied summary judgment on the trespass count.

Still, the Court pretty much savaged Ev’s and Maggie’s rather shrill and frantic claim, leaving their all-encompassing nuisance broadside a rather puny trespass and trim of a single tree.

– Tom Root

The United States inherited the law of trespass from medieval England. At common law, a trespass upon land occurred when a person, acting without authority, physically invades or unlawfully enters the premises of another, and damages result (even though the damages may be insignificant). The entry may be intentional or negligent. Just about every entry onto the land of another that occurs happens due to negligence, because it requires remarkably little negligence to accomplish a trespass.

The United States inherited the law of trespass from medieval England. At common law, a trespass upon land occurred when a person, acting without authority, physically invades or unlawfully enters the premises of another, and damages result (even though the damages may be insignificant). The entry may be intentional or negligent. Just about every entry onto the land of another that occurs happens due to negligence, because it requires remarkably little negligence to accomplish a trespass. Trespass is most commonly asserted by people who have lost trees to a misguided tree cutter taking timber on the wrong side of an unclear or misunderstood property line. It has also been applied where people took self-help a little too far, and went onto neighboring property to aggressively trim a problem tree. Trespass has been found where people mistakenly believed they owned the property they had occupied, where a party has negligently caused livestock or water to enter another’s land, and where someone was on the property with permission to cut down certain trees, but cut down trees he had been told to avoid.

Trespass is most commonly asserted by people who have lost trees to a misguided tree cutter taking timber on the wrong side of an unclear or misunderstood property line. It has also been applied where people took self-help a little too far, and went onto neighboring property to aggressively trim a problem tree. Trespass has been found where people mistakenly believed they owned the property they had occupied, where a party has negligently caused livestock or water to enter another’s land, and where someone was on the property with permission to cut down certain trees, but cut down trees he had been told to avoid. The Court of Appeals reversed, providing some basic guidance on the law of trespass in the process. It said the evidence failed to prove the elements of either trespass or conversion. Common-law trespass, the Court said, is the unauthorized entry by a person upon land of another. For damages to be awarded for trespass, a plaintiff has to show that the defendant intended to be on the property and that he directly interfered physically with that property. Removing trees from someone else’s property may also be a statutory trespass. A person can wrongfully cut down a tree in two ways, either of which would result in trespass under § 537.340 RSMo. He can enter the land without permission and cut down the trees. Alternatively, he can enter with the owner’s consent and then exceed the scope of the consent by cutting down trees without permission.

The Court of Appeals reversed, providing some basic guidance on the law of trespass in the process. It said the evidence failed to prove the elements of either trespass or conversion. Common-law trespass, the Court said, is the unauthorized entry by a person upon land of another. For damages to be awarded for trespass, a plaintiff has to show that the defendant intended to be on the property and that he directly interfered physically with that property. Removing trees from someone else’s property may also be a statutory trespass. A person can wrongfully cut down a tree in two ways, either of which would result in trespass under § 537.340 RSMo. He can enter the land without permission and cut down the trees. Alternatively, he can enter with the owner’s consent and then exceed the scope of the consent by cutting down trees without permission.