TREE TRESPASS LOTTERY

There are a lot of moving parts to today’s case. First, we have the classic setup for treble damages. A neighbor is told repeatedly that his beliefs as to his property boundaries were wrong, but he pigheadedly ignores the news he does not want to hear. After the inevitable trespass results in the butchering of hundreds of trees, the unhappy victims – who don’t want justice as much as a pound of flesh – decide to pile on with multiple experts, each describing the loss a little differently. Finally, we have a plaintiff’s lawyer who screws up on a minor and rather technical rule of pleading, costing his clients some money in the process.

There are a lot of moving parts to today’s case. First, we have the classic setup for treble damages. A neighbor is told repeatedly that his beliefs as to his property boundaries were wrong, but he pigheadedly ignores the news he does not want to hear. After the inevitable trespass results in the butchering of hundreds of trees, the unhappy victims – who don’t want justice as much as a pound of flesh – decide to pile on with multiple experts, each describing the loss a little differently. Finally, we have a plaintiff’s lawyer who screws up on a minor and rather technical rule of pleading, costing his clients some money in the process.

In any fair contest, the Linebargers should have gotten treble damages from their neighbor George. How many times do you have to be put on notice that your purported property lines place you at risk of committing a whopper of a timber trespass before you check your figures, just to be safe?

Still, the punishment ought to fit the crime. Like the Alaska case we considered a few months ago, compensation for loss is one thing. But a lottery ticket that would score you two-thirds of the fair market value of your 30-acre spread for the loss of 4 acres of trees just seems wrong.

No one should quibble with the Linebargers getting treble damages. Pigheaded George had it coming. But their lawyer somehow forgot to ask for treble damages in his complaint, or even at trial. A basic tenet of procedural due process is that a defendant should get notice of what the plaintiff wants to stick him or her with, and an opportunity to put on as good a defense as the defendant can muster and the law allows.

In today’s litigious world, the Linebargers would have gone after their lawyer’s malpractice policy the day after the appeals court ruled.

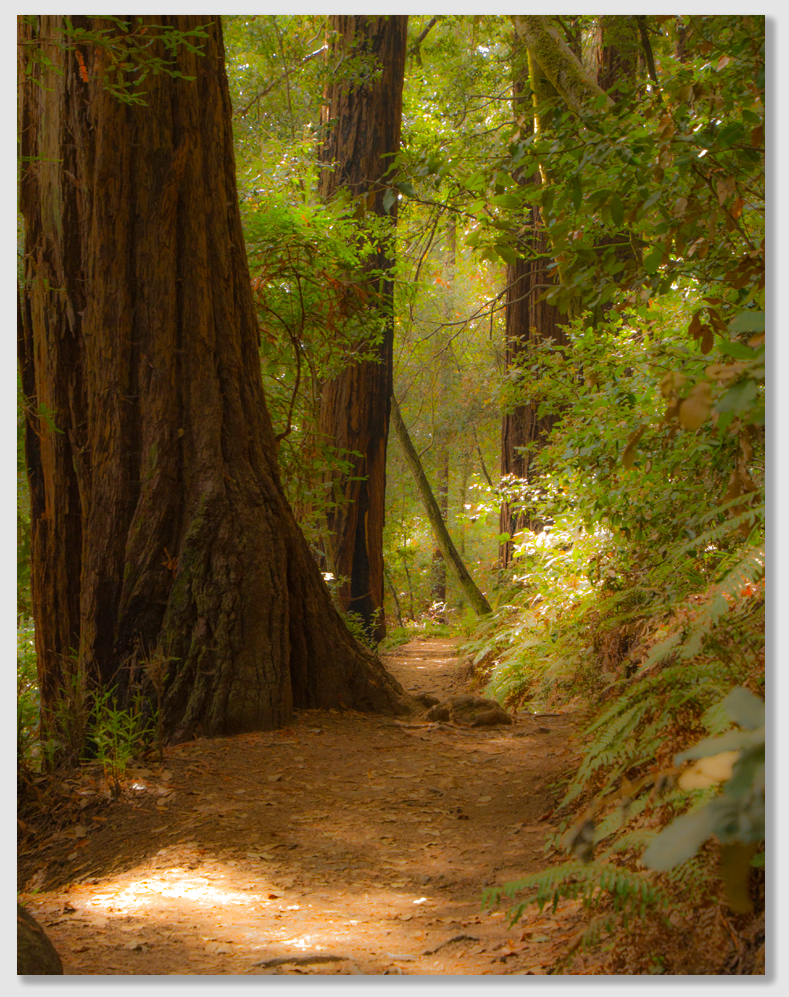

Linebarger v. Owenby, 79 Ark.App. 61, 83 S.W.3d 435 (Ark.App. 2002). George Owenby’s property lies south of a heavily wooded, 30-acre tract owned by Jerry and Margaret Linebarger. The Linebargers bought the northern 20 acres of their property in 1976, where they built a weekend cabin. They bought the southern 10 acres in 1993 to serve as a buffer between their cabin and neighboring lands.

Linebarger v. Owenby, 79 Ark.App. 61, 83 S.W.3d 435 (Ark.App. 2002). George Owenby’s property lies south of a heavily wooded, 30-acre tract owned by Jerry and Margaret Linebarger. The Linebargers bought the northern 20 acres of their property in 1976, where they built a weekend cabin. They bought the southern 10 acres in 1993 to serve as a buffer between their cabin and neighboring lands.

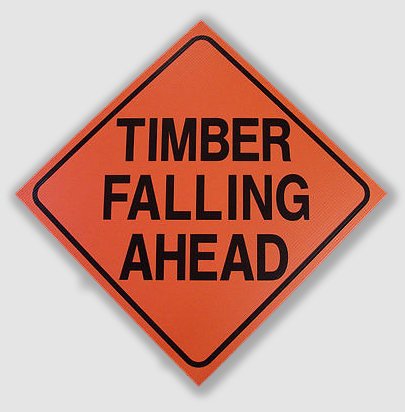

In 1998, George sold the timber on his tract to Canal Wood Corporation. Canal Wood began cutting in the fall of 1998 and, in the process, cut 329 trees from the southern 10 acres of the Linebargers’ land. Jerry complained that he had tried to tell George for years that a 1987 survey George used to establish his boundary was wrong, and that there was a more recent survey available.

As late as December 1997, when George told Jerry he was thinking of selling his timber, Jerry reminded George of the boundary problem and asked George to call him before proceeding. Heedless of this good advice, George made his deal with Canal, and, when Canal noticed some evidence of a boundary different than the one George had indicated, George provided Canal with the 1987 survey. In reliance on the wrong survey, Canal marked the acreage in such a manner that some of the Linebargers’ trees were cut.

Jerry and Marge finally got George’s attention by suing him and Canal for trespass and destruction of trees “that had been used for shade and beauty.” They asked for damages that would allow them to replace the lost trees, for attorney fees and costs, and for anything else to which they might be entitled. At trial, the Linebargers offered the testimony of three experts as to the amount of damages they had suffered. One expert, Bill Kelly, said the stumpage value of the cut trees was $1,081.60 and that it would cost $643.50 to prepare the site for re-planting. Another expert, real estate appraiser Wayne Coates, testified the market value of appellants’ property was $68,000 before the cutting and $62,000 afterward (which included $3,000 in clean-up costs). A third expert, Al Einert, placed a value on every tree that had been cut and determined the total value of the trees to be $44,702. Naturally, the Linebargers liked Al’s number the best.

Jerry and Marge finally got George’s attention by suing him and Canal for trespass and destruction of trees “that had been used for shade and beauty.” They asked for damages that would allow them to replace the lost trees, for attorney fees and costs, and for anything else to which they might be entitled. At trial, the Linebargers offered the testimony of three experts as to the amount of damages they had suffered. One expert, Bill Kelly, said the stumpage value of the cut trees was $1,081.60 and that it would cost $643.50 to prepare the site for re-planting. Another expert, real estate appraiser Wayne Coates, testified the market value of appellants’ property was $68,000 before the cutting and $62,000 afterward (which included $3,000 in clean-up costs). A third expert, Al Einert, placed a value on every tree that had been cut and determined the total value of the trees to be $44,702. Naturally, the Linebargers liked Al’s number the best.

The trial judge found that Canal had failed to obtain a survey prior to cutting the trees and had trespassed on the Linebarger’s land as the result of George’s intentional failure to disclose the correct survey. However, the judge found that the $44,702 damage figure testified to by Al was disproportionate in relation to the fair market value of the land. He awarded the Linebargers $5,000 for the reduction in value of their land, based on Wayne Coates’s testimony, plus $1,081.60 stumpage value and $643.50 in clean-up costs, based on Bill Kelly’s testimony.

The Linebargers appealed.

Held: The replacement value of the trees was grossly disproportionate to the diminution of the land value, and would be a windfall for the Linebargers.

The Linebargers complained that the trial court should have awarded them the $44,702 replacement value of the trees. Arkansas courts have recognized that when ornamental or shade trees are injured, the use made of the land should be considered, and the owner should be compensated for the cost of replacing the trees. However, fact situations may arise in which recovery of the replacement cost of trees would yield a result grossly disproportionate to the fair market value of the land and thus would be an inappropriate measure of damages. The evidence in each case determines what measure of damages is to be used.

Here, the trial judge acknowledged the Linebargers had used their trees for screening and shade, and he gave due consideration to the replacement measure of damages. However, he found that most of the trees cut were behind and over the crest of a hill from Jerry and Marge’s cabin, which tended to reduce the harm they suffered. After all, you can’t derive shade from trees you can’t see. He also found that the replacement cost of the trees would be disproportionate in relation to the fair market value of the land.

Here, the trial judge acknowledged the Linebargers had used their trees for screening and shade, and he gave due consideration to the replacement measure of damages. However, he found that most of the trees cut were behind and over the crest of a hill from Jerry and Marge’s cabin, which tended to reduce the harm they suffered. After all, you can’t derive shade from trees you can’t see. He also found that the replacement cost of the trees would be disproportionate in relation to the fair market value of the land.

The Court of Appeals agreed. “We cannot say that the trial judge abused his discretion in making the damage award,” the Court wrote. “Although he recognized that an award of replacement value might be possible, he declined to use that measure of damages because 1) the cut trees were behind and over a crest from the cabin, and 2) the replacement value would be disproportionate to the land value. The location of the cut trees in relation to the cabin is a legitimate factor to consider. The trees provided only minimal shade, ornamental, or landscaping value to the appellants’ residence.”

It was obviously meaningful to the appellate court that if George paid the Linebargers the full replacement value of $44,702 for trees cut on 4.29 acres, Jerry and Marge would have received 67% of the value of the entire 30 acres as a whole (including the cabin). Such an award would exceed the stumpage value of the cut trees by over $43,000.

The Linebargers cited Ark. Code Ann. § 18-60-102 (a), which provides that if a person cuts down another’s tree, he may be liable for treble damages. Here, the Court replied, the trial judge found that the wrongful cutting in this case occurred through George’s intentional conduct. In cases of intentional wrongdoing involving the cutting of trees, the victim may recover treble damages. But despite his finding of intentional conduct, the judge declined to award treble damages in this case, based on the idea that a court of equity cannot award treble damages.

The judge was right, the appellate court said, but for the wrong reason. Jerry and Marge did not include a request for treble damages in their pleading, nor does the record reveal that they notified George and Canal at trial that they would be seeking exemplary (punitive) damages. A defendant is entitled to be given adequate notice of the remedy he or she will be confronting. An award of treble damages would have been inappropriate in the absence of the Linebargers pleading for them or the issue being tried with the express or implied consent of the parties.

– Tom Root