THE MASSACHUSETTS RULE GETS FLUSHED

Gloria Lane was a down-on-her-luck middle-aged woman who managed to just eke out an existence with her disabled brother in an old house. Their place was next to a rental property, a house equally as old, but owned by a corporate slumlord, W.J. Curry & Sons.

Do you see where this one is going? Hard cases can make bad law. Even where the result isn’t necessarily wrong — and we’re not hard-hearted enough to criticize people who were too poor to afford to fix the bathroom — cases are fact-driven.

We can imagine the scenario: a faceless corporation rolling in dough, too chary to keep up its properties and too avaricious to pay damages inflicted on the impoverished neighbors. That, at least, is the innuendo.

The Curry property included three large, healthy oak trees near the boundary with the Lane homestead. The trees are much taller than either of the houses, and those towering oaks featured limbs that protruded over Gloria Lane’s house and caused manifold problems. First, the court said, she had to replace her roof 15 years before the lawsuit “because the overhanging branches did not allow the roof to ever dry, causing it to rot.” She complained that prior to replacing the roof, “[e]very roof and wall in [her] house had turned brown and the ceiling was just falling down. We would be in bed at nighttime and the ceiling would just fall down and hit the floor.”

In 1997, one of the oaks shed a large limb, which fell through the Lanes’ roof, attic, and kitchen ceiling. Rain then ruined her ceilings, floor, and the stove in her kitchen. The Lanes were physically unable to cut the limbs back that were hanging over the house, and they couldn’t afford to hire it done. For that matter, Gloria couldn’t even afford to fix the hole in her roof.

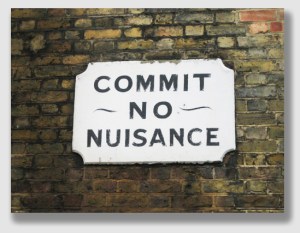

If that weren’t enough, the oaks’ roots clogged the Lane’s sewer line, causing severe plumbing problems. Gloria tried to chop the encroaching roots away from the sewer over the years, but they kept growing back and causing more plumbing problems. At the time of the lawsuit, she hadn’t been able to use her toilet, bathtub, or sink in two years because of the clogs. Instead, she went to the neighbors’ house (presumably not the Curry rental) to use the toilet. Meanwhile, raw sewage was bubbling into her bathtub, and the bathroom floor had to be replaced because of toilet back-ups and water spills onto the floor.

If that weren’t enough, the oaks’ roots clogged the Lane’s sewer line, causing severe plumbing problems. Gloria tried to chop the encroaching roots away from the sewer over the years, but they kept growing back and causing more plumbing problems. At the time of the lawsuit, she hadn’t been able to use her toilet, bathtub, or sink in two years because of the clogs. Instead, she went to the neighbors’ house (presumably not the Curry rental) to use the toilet. Meanwhile, raw sewage was bubbling into her bathtub, and the bathroom floor had to be replaced because of toilet back-ups and water spills onto the floor.

Gloria told the trial court that “everything is all messed up. I can’t bathe. I can’t cook. I don’t want people coming to my house because it has odors in it, fleas, flies, bugs. It’s just been awful for me.” Ms. Lane, already under a psychiatrist’s care, said she “just can’t take too much more.”

After the branch punched a hole in her roof, Gloria asked the owner of W.J. Curry – one Judith Harris, a corporate minion who was neither W.J. nor any of his sons – to do something. She had a tree service trim the lower branches, but not the ones that would have been more expensive to reach. This didn’t solve the problems. When Gloria complained again, Ms. Harris told Gloria that she was on her own.

Now, boys and girls, these are hard facts. We aren’t dealing with the Schwalbachs, who were perfectly fit and reasonably flush, complaining about a few twigs and leaves to an underfunded cemetery association. Here, we have a dramatis personae that includes – as protagonist – a pathos-inducing poor woman caring for an invalid sibling, and – as antagonist – a soulless corporation destroying her happy home, one dropped limb by one dropped limb by one rotten roof by one clogged sewer at a time. And we’ve got some real damages, too. You try knocking on the neighbor’s door eight times a day and night to use the ‘loo, and see how you feel. Did the Massachusetts Rule have any chance of survival in the face of this heart-wrenching tale?

Of course not. The evil slumlord defendant (and we don’t know that he was evil or even a slumlord, but the story has a life of its own) argued that Tennessee followed the Massachusetts Rule. After all, it pointed out, Gloria was free to fire up her Husqvarna and clamber out onto her roof herself to cut down the offending limbs. Tennessee law firmly established that her remedies were limited to Massachusetts-style “self-help.” That means Gloria should get nothing for the hole in her roof, nothing for her falling plaster, nothing for her waterlogged stove, and nothing for the sewage bubbling in her bathtub.

Of course not. The evil slumlord defendant (and we don’t know that he was evil or even a slumlord, but the story has a life of its own) argued that Tennessee followed the Massachusetts Rule. After all, it pointed out, Gloria was free to fire up her Husqvarna and clamber out onto her roof herself to cut down the offending limbs. Tennessee law firmly established that her remedies were limited to Massachusetts-style “self-help.” That means Gloria should get nothing for the hole in her roof, nothing for her falling plaster, nothing for her waterlogged stove, and nothing for the sewage bubbling in her bathtub.

The trial court agreed with W.J. Curry. It held that while it was “certainly a serious situation that the plaintiff has not been able to use her bathroom for two years … these three trees are alive and living and they do what trees normally do. They produce branches and grow and they produce a root system. And even though you trim the branches back or you trim the roots back, they are going to produce more branches and more roots.”

Spoken like a judge whose own toilet flushes just fine. The three-judge appellate panel – a trio of jurists who also were not worrying about the efficacy of their respective commodes – agreed. They observed that, after all, the trees were not “noxious” (which was a quaint notion championed by Smith v. Holt but since abandoned in Fancher v. Fagella).

The Tennessee Supreme Court reversed, adopting the Hawaii Rule, holding that living trees and plants are ordinarily not nuisances, but can become so when they cause actual harm or pose an imminent danger of actual harm to adjoining property. When that happens, the Court said, the owner of the tree had some responsibility to clean up the mess. No doubt swayed by the extensive record of travail propounded by Ms. Lane, the Court held that W.J. Curry’s trees clearly satisfied the definition of a “private nuisance.” It sent the case back to the trial court for a remedy to be crafted, one that no doubt included money damages and probably an order that the landlord cut down the oversized trees.

Lane v. W.J. Curry & Sons, 92 S.W.3d 355 (Tenn. 2002). The long-suffering Gloria Lane sued W.J. Curry and Sons, Inc. a landlord owning a rental property next to her house. Over the years, her roof was damaged by branches overhanging from oaks growing on the Curry property, a branch fell, smashing into the home and causing extensive damage, and the root system substantially damaged her sewer system, rendering her home almost uninhabitable.

Gloria sued, asserting that encroaching branches and roots from the Curry trees constituted a nuisance for which she was entitled to seek damages. W.J. Curry responded that Ms. Lane’s sole remedy was Massachusetts Rule-style self-help, and she could not recover for any harm caused by the trees.

The trial court and Court of Appeals agreed with W.J. Curry and Sons, holding that an adjoining landowner’s only remedy in a case like this one was self help, and that a nuisance action could not be brought to recover for harm caused by encroaching tree branches and roots.

Ms. Lane appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court.

Held: Self-help is not an adjoining landowner’s sole remedy when tree branches and roots encroach. A nuisance action may be brought when the encroaching branches and roots damage the neighboring landowner’s property.

The Supreme Court held that although encroaching trees and plants are not nuisances merely because they cast shade, drop leaves, flowers, or fruit, or just because they encroach upon adjoining property either above or below the ground, they may be regarded as a nuisance when they cause actual harm or pose an imminent danger of actual harm to adjoining property. If so, the owner of the tree or plant may be held responsible for harm caused by it and may also be required to cut back the encroaching branches or roots, assuming the encroaching vegetation constitutes a nuisance.

The Court engaged in a lengthy discussion of the various theories of liability adopted in various states, including the Massachusetts Rule, the Hawaii Rule, and the old, pre-Fancher Virginia Rule. The Court decided that the Hawaii Rule should be followed, because it “voices a rational and fair solution, permitting a landowner to grow and nurture trees and other plants on his land, balanced against the correlative duty of a landowner to ensure that the use of his property does not materially harm his neighbor,” while being “stringent enough to discourage trivial suits, but not so restrictive that it precludes a recovery where one is warranted.” The Court criticized the Massachusetts Rule, agreeing with the notion that limiting a plaintiff’s remedy to self-help encourages a “law of the jungle” mentality by replacing the law of orderly judicial process with the doctrine of “self-help.” Yet, the Court said, the Hawaii Rule was consistent with the principle of self-help Tennessee courts had previously enunciated.

The Court was careful to note that it was not altering existing Tennessee law that the adjoining landowner may, at his own expense, cut away the encroaching vegetation to the property line – whether or not the encroaching vegetation constitutes a nuisance or is otherwise causing harm or potential harm to the adjoining property.

– Tom Root