HURTS SO BAD

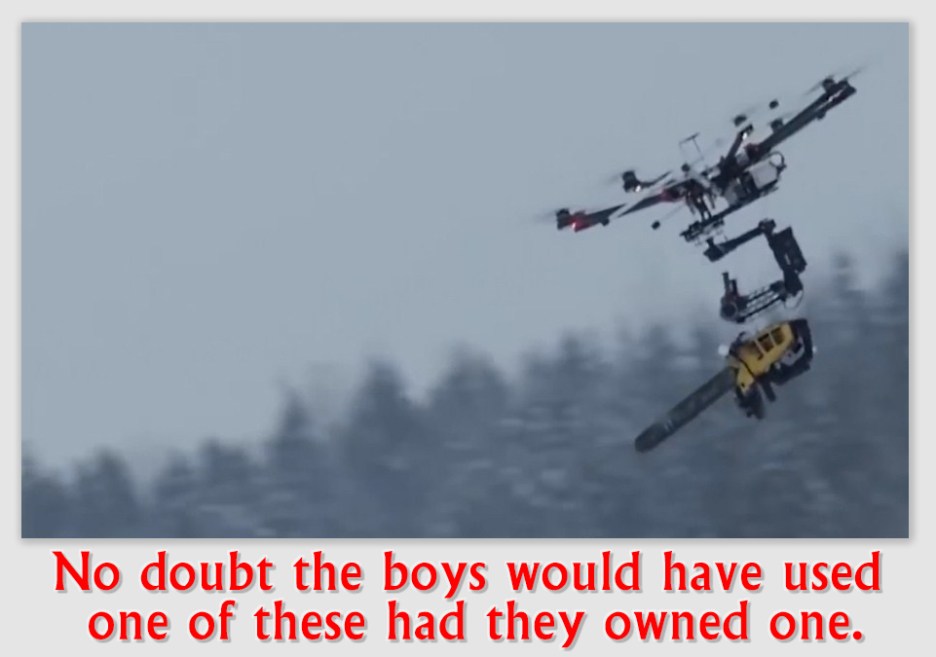

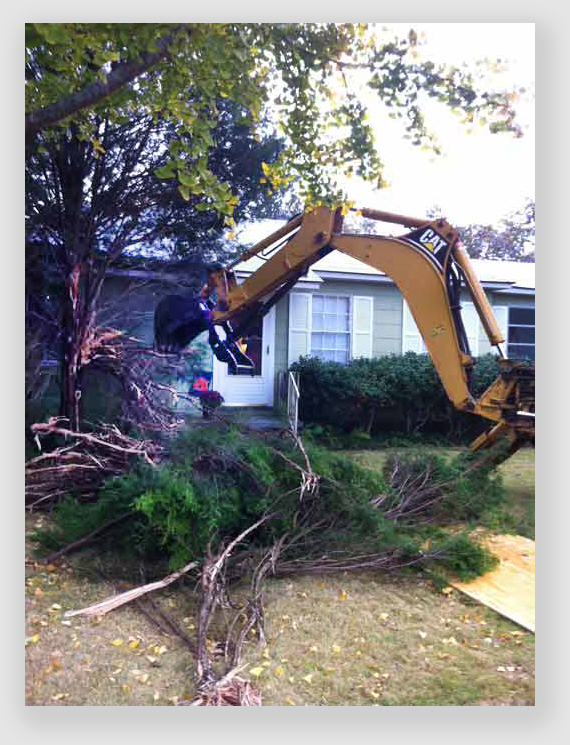

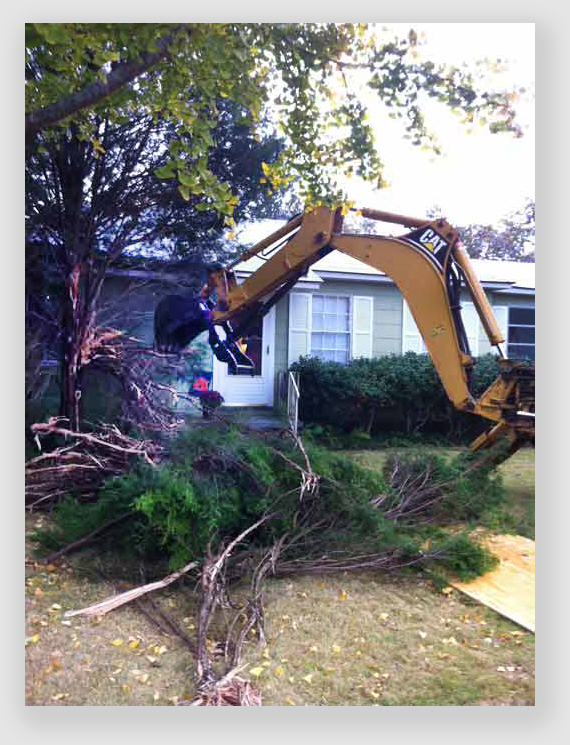

In case you missed it the past two days, this is a trackhoe removing a tree.

Today is our last day down on Dick Lavy’s Darke County farm. As you recall, we helped Dick’s faithful employee Sylvester trim the trees along a fencerow that separated one of the Lavy from land belonging to his neighbor, Jim Brewer.

We were fairly impressed to watch Sylvester run a trackhoe down the Lavy side of the fencerow, smacking down branches with the machine’s bucket. It was not pretty, but it got the job done effectively and cheaply.

Jim Brewer, however, wasn’t very happy with the result and sued Dick Lavy Farms. Farmer Lavy argued the Massachusetts Rule let him trim overhanging trees any way he liked, that Sylvester wasn’t negligent or reckless, and that the damage – if there even was damage – didn’t amount to much. The jury thought it was arboricide and socked Farmer Lavy for $148,350.

Last Thursday, we watched the Court of Appeals for Darke County, Ohio, fillet Dick Lavy’s argument that the Massachusetts Rule was a license to butcher. The Court affirmed a landowner’s right to trim encroaching trees and roots to the property line but held that such trimming had to be done in a reasonable manner so as not to injure the adjoining owner’s trees.

On Friday, we saw the Court compare the various means of trimming a fencerow, comparing for ease of use, custom in the area, and cost. It concluded that the trial court was right to find DLF negligent in trimming part of the fencerow and reckless in continuing after a sheriff’s deputy advised Dick Lavy to get legal advice before continuing (advice the farmer ignored).

Today, the Court delves into the $148,350 damage award. Clearly, the Court is troubled that Jim only paid $170,000 for the whole 70 acres, and provided no evidence that the value of the land fell a farthing because of Sylvester’s trimming activities. The Court felt hard-pressed to see Jim get almost $150,000 when no trees other than some saplings were destroyed.

Jim didn’t help his cause by admitting (as he had to) that he only visited the land about eight times a year to hunt and picnic, and the trimming didn’t interfere with those activities. He argued that he planned to build a house there in another 14 years or so, but the Court couldn’t see that the damaged fencerow trees had any impact on those plans.

Usually, the measure of damages for a trespass where trees are cut is the difference in the land’s value after the cutting versus before the cutting. There are times when this measure does not capture the real loss: a family loses a cherished ornamental tree, for example, or the landowner nurtures trees for their ecological value.

That’s what Jim Brewer claimed, too…

In this case, however, it’s hard to see how Jim was hurt at all, not to mention hurt as badly as he claimed to be. Indeed, that’s how the Court of Appeals seems to read it, too. Come with us now on a detailed and thoughtful journey through all of the matters a court (and aggrieved party) should consider in setting the amount of loss. Although the Court sends the damage award back for the trial judge to deal with, it’s quite clear that the appellate panel is disinclined to turn the case into a winning lottery ticket for Jim Brewer.

Brewer v. Dick Lavy Farms, LLC, 2016-Ohio-4577 (Ct.App. Darke Co., June 24, 2016)

(These facts are repeated from the previous two days: If you don’t need the refresher, skip to the holding)

In 2007, James Brewer bought about 70 acres of rural property for $180,000. About 30 acres of the land were tillable, and 40 acres were wooded. The only access to the tillable and wooded property was a 25-foot wide lane of about 3,600 feet in length.

The former owner had allowed his neighbor Dick Lavy Farms to farm the property, and the lane had not been used. Brewer cleared the lane of undergrowth in order to access the rest of the property. The lane ran west to east, and had trees on both sides of the lane, with the trees on the south side forming a fencerow between Brewer’s property and land owned by Dick Lavy Farms. The trees in the fencerow were a woodland mix; none of the trees were ornamental or unique.

In January 2013, Dick Lavy ordered an employee to clear the fencerow between the two properties. At the time, Lavy understood that he could clear brush straight up and down the property line and that such clearing was important for crop production, yield and safety of farm equipment. Using a track hoe, which had an arm that could reach about 15 feet in the air, the employee reached up, grabbed limbs, and pulled on them, trying to break them off cleanly. Although the employee tried to keep the trackhoe on DLF’s side of the property, occasionally a branch would snap off or tear the tree on Brewer’s side. Occasionally, a branch would fall on Brewer’s side, and the employee would reach over to grab the branch Sylvester stated that he never consciously reached over with the bucket to try and break a branch at the tree trunk that was on Brewer’s side of the property.

When Brewer learned that DLF was clearing the fencerow, he went out to look at the operation and called the sheriff. At that point, the track hoe was about halfway down the fencerow, destroying trees. A Darke County sheriff’s deputy told Lavy that a complaint had been made, and expressed his concern that civil or criminal issues could be involved in what he was doing. Lavy said that he had a right to take down any branches that were hanging over his property. In addition, Lavy said he would let Brewer remove the branches if Brewer wanted to do so, but he wanted the branches removed before crop season began in March or April.

Or, if you’re Sylvester, don’t use a chainsaw at all…

The deputy told Brewer that Lavy said that he was allowed to take tree branches from his side and that if Brewer did not like the way he was doing it, Brewer could cut them himself. Brewer told the deputy that he was going to have an expert look at the trees. The deputy filed a report with the prosecutor’s office, but no charges were brought.

Although the deputy suggested that Lavy obtain legal advice before continuing, Lavy continued clearing the fencerow. Knowing that Brewer was upset, Lavy told his employee not to clean up branches that fell on Brewer’s side.

Within days after the damage occurred, Brewer’s wife took photos of the damaged trees. Three months later, Brewer and an arborist counted 326 damaged trees.

Brewer sued Dick Lavy Farms, alleging a violation of O.R.C. § 901.51, reckless trespass, and negligent trespass. Prior to trial, the court held that Brewer was not limited to damages for diminution in value, and the court would apply a standard that allowed recovery of the costs of restoration.

DLF argued that it had a common law privilege to cut off, destroy, mutilate or otherwise eliminate branches from Brewer’s trees that were overhanging DLF land. The Farm also argued that if it was liable, the proper measure of damages should be the diminution of Brewer’s property value; in the alternative, the court’s holding on the issue of damages was against the manifest weight of the evidence. Finally, DLF claimed it had not negligently or recklessly trespassed on Brewer’s property.

The Court found for Brewer, awarding him $148,350 in damages, including treble damages of $133,515.

Dick Lavy Farms appealed.

(If you remember the facts from the previous two days, start here)

Held: It was Halloween for Jim, and he got a trick, not a treat. The $148,350 in damages was set aside because Jim’s property really didn’t diminish in value.

The Court observed that in a previous case, it had held that where the trespasser could not reasonably foresee that trees had a special purpose or value to the landowner, and where the trespasser “cuts trees that are part of a woodland mix and not unique, the ordinary measure of the harm is the difference in the fair market value before and after the cutting.” The trial court, however, had relied on a different standard:

It was all trick and no treat for Jim…

In an action for compensatory damages for cutting, destroying and damaging trees and other growth, and for related damage to the land, when the owner intends to use the property for a residence or for recreation or for both, according to his personal tastes and wishes, the owner is not limited to the diminution in value (difference in value of the whole property before and after the damage) or to the stumpage or other commercial value of the timber. He may recover as damages the costs of reasonable restoration of his property to its preexisting condition or to a condition as close as reasonably feasible, without requiring grossly disproportionate expenditures and with allowance for the natural processes of regeneration within a reasonable period of time.

At trial, Jim’s expert arborist testified that the cost of removing the trees Sylveste3r had damaged would cost $55,000, and the cost of replacing them would be $138,000, plus tax. Jim did not offer any evidence that his 70-acre property’s fair market value had fallen by so much as a penny. DLF’s arboriculture expert testified the life expectancy and service life functionality of the fencerow were not affected by the manner in which the trees were pruned. He valued the fencerow as a woodland edge fence and argued that real estate or fair market value would be the proper way to assess damages. Another DLF expert also testified that the fair market value of Brewer’s property was the same before and after the incident.

The trial court found that removal of the damaged trees was unnecessary, and thus discounted that $55,000 cost. In addition, the court concluded that the $138,000 estimate for tree replacement was excessive, and reduced that amount by 50%. The court also deducted 14% for ash tree disease, which had already caused the death of a number of trees on both sides of the lane. The trial court thus arrived at $59,340 in compensatory damages.

Next, the trial judge decided that DLF had negligently trimmed one-fourth of the property (or about 1,000 feet), and recklessly trimmed the remaining three-fourths of the fencerow. The trial court awarded $14,835 for negligence, and $44,505 for DLF’s recklessness. Pursuant to O.R.C. § 901.51, the court trebled the recklessness amount to $133,515. This brought the total damages to $148,350.

The Court of Appeals noted Ohio’s general rule that “recoverable restoration costs are limited to the difference between the pre-injury and post-injury fair market value of the real property,” The courts have carved out an exception, however, that permits restoration costs to be recovered in excess of the decrease in fair market value when real estate is held for noncommercial use, when the owner has personal reasons for seeking restoration, and when the decrease in fair market value does not adequately compensate the owner for the harm done. This restoration cost exception has been applied, for example, where the damaged trees have been maintained for a specific, identifiable purpose (like recreation, or a sight, sound, or light barrier), when damaged trees are essential to the planned use of the property, or when the damaged trees had a value that can be calculated separate from ornamental trees have been destroyed, or where the trees form part of an ecological system of personal value to the owner.

Even where the restoration exception is applied, the Court said, “the proposed cost [cannot be] grossly disproportionate to the entire value of the injured property.”

The Court said that the damage to Jim Brewer’s trees was “temporary” (meaning, apparently, that the damaged limbs would grow back), and that the Ohio rule is that “damages for temporary injury to property cannot exceed the difference between market value immediately before and after the injury, is limited. In an action based on temporary injury to noncommercial real estate, a plaintiff need not prove diminution in the market value of the property in order to recover the reasonable costs of restoration, but either party may offer evidence of diminution of the market value of the property as a factor bearing on the reasonableness of the cost of restoration.”

The trial court seemed certain that Dick Lavy was a deep pocket, and that may have driven its damage award.

“Viewing the trial court’s award of damages from the perspective of reasonableness,” the Court of Appeals said, “we must conclude that the award for restoration was objectively unreasonable.” First, the application of O.R.C. § 901.51 “almost exclusively involves situations where trees have been completely cut down, making it considerably easier to determine the full extent of the damage to the plaintiffs’ property.” Here, Jim Brewer admitted that other than a few small saplings, he was not claiming that any large trees had been removed from his land. Instead, he contended only “that 326 trees had been damaged in some manner and would ultimately die, even though pictures of the area taken in June 2014 depict a substantial canopy of foliage… Brewer also testified that a number of trees had died, but he did not give any specific number.”

The Court found that Jim Brewer’s trees were not ornamental and were not located at his residence. Instead, they were native trees that were just part of a fencerow. Jim testified he used the property for hunting only about six times a year, and for family get-togethers maybe twice a year. He also admitted the removal of branches had not had any effect on these activities or his ability to rent tillable land to farmers. Jim intended to put a house on the property after his 4-year-old child graduates from high school, but he didn’t claim that DLF’s tree trimming affected his plans to do so.

The Court found it noteworthy that Jim Brewer paid $180,000 for all 70 acres, yet claimed the restoration cost (including removal and replanting of trees) for a very small part of that property was more than $200,000.

Jim did not present any proof that the fair market value of the land had fallen because of the tree trimming. The Court agreed that he was not required to present such evidence, bur said “it would have been helpful, particularly since two defense witnesses indicated that removing vegetation from the fence row did not impact the fair market value of the land.” Additionally, the Court found that much of the trial judge’s calculations “were based on speculation or were incorrect. For example, the court concluded that one-fourth of the fence row was trimmed negligently, but the plaintiff’s own evidence showed that more like 1,800 feet had been trimmed when Jim Brewer first complained. “The trial court could have chosen to disregard [the DLF employee’s] testimony,” the Court said, “but there is no logical reason to disregard the plaintiffs’ own admission about how far the fence row had been cleared.”

The Court of Appeals was not inclined to see Jim Brewer get a winning lottery ticket…

The trial court also gave no particular reason for its 50% discount on damages. What’s more, the Court of Appeals complained, “The trees on the fence row were a woodland mix of native trees, not ornamental trees. A number of the trees were undesirable, and there was no evidence of special value. In addition, the fence row had been unmaintained for 10 or 29 years. Even though these facts no longer require damages to be limited to diminution in value, they are still points that should be considered in deciding whether an award is reasonable.”

The Court of Appeals vacated the damages, and directed the trial court on remand to consider the reasonable restoration costs, taking into consideration the decrease in the fair market value of the land; the fact that the trees were a common woodland mix, not ornamental trees or trees that Jim had planted for a particular purpose; the fact that the fence row was not maintained for many years, and had undesirable and dead trees on each side of the row; the extent to which the trees have regenerated since the date of the 2013 trimming; the lack of impact on Jim’s intended home site; and the fact that Jim’s use of his property is “sporadic and is not impacted by any injury to the trees.”

The detailed list of evidence the trial court is to consider pretty much tells the trial judge how the Court of Appeals expects this to turn out.

– Tom Root

Intentional grounding? You can bet that was the call after Mr. and Mrs. Peters bought a lot next to the Kriegs.

Intentional grounding? You can bet that was the call after Mr. and Mrs. Peters bought a lot next to the Kriegs. C’mon, the Peterses said, there wasn’t any evidence they knew they were cutting Kriegs’ trees. The Court pointed out that the state of the evidence was precisely the problem. It was up to the Peterses to prove that they thought the land was theirs. The wife’s testimony was all they had offered, and it didn’t help: she explained they didn’t really know where the boundaries were, and never bothered to find out. But the biggest problem was what Mr. Peters testified to: nothing. He was the one who cut the trees down, and the Court seemed to expect that he would have material testimony to offer. But he didn’t testify.

C’mon, the Peterses said, there wasn’t any evidence they knew they were cutting Kriegs’ trees. The Court pointed out that the state of the evidence was precisely the problem. It was up to the Peterses to prove that they thought the land was theirs. The wife’s testimony was all they had offered, and it didn’t help: she explained they didn’t really know where the boundaries were, and never bothered to find out. But the biggest problem was what Mr. Peters testified to: nothing. He was the one who cut the trees down, and the Court seemed to expect that he would have material testimony to offer. But he didn’t testify. There’s a well-known principle in evidence known generally as the “missing witness instruction.” As the legendary Professor Wigmore put it, the principle holds that “the nonproduction of evidence that would naturally have been produced by an honest and therefore fearless claimant permits the inference that its tenor is unfavorable to the party’s cause.” In other words, if you have particular control of evidence, and you do not bring it forward, a court is allowed to assume it would have been harmful to your cause if you had done so.

There’s a well-known principle in evidence known generally as the “missing witness instruction.” As the legendary Professor Wigmore put it, the principle holds that “the nonproduction of evidence that would naturally have been produced by an honest and therefore fearless claimant permits the inference that its tenor is unfavorable to the party’s cause.” In other words, if you have particular control of evidence, and you do not bring it forward, a court is allowed to assume it would have been harmful to your cause if you had done so. Held: The treble damages were upheld. Under RPAPL §861[2], the New York treble damage statute, in order to avoid treble damages, the Peterses had the burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that when they removed the trees from the Kriegs’ property, they “had cause to believe the land was [their] own.” Their proof in this regard was woefully inadequate. Mrs. Peters was the only defense witness to testify on this critical issue, and the appellate court found that her testimony had been more damning than helpful in sustaining their burden. She said that, before she and her husband purchased the property, she walked it on one occasion with their realtor. At that time, she specifically asked about the boundary lines but the realtor couldn’t answer her question with any certainty. She said she told her husband of the realtor’s uncertainty when they later walked the property together. She also candidly admitted that no steps were taken to obtain a survey or consult the map referenced in their deed before clearing the land. The Court found it significant that, although he had logged the property, Mr. Peters never testified. It found plenty of evidence that the defendants had no cause to know whether the land Mr. Peters was logging belonged to them or not.

Held: The treble damages were upheld. Under RPAPL §861[2], the New York treble damage statute, in order to avoid treble damages, the Peterses had the burden of proving by clear and convincing evidence that when they removed the trees from the Kriegs’ property, they “had cause to believe the land was [their] own.” Their proof in this regard was woefully inadequate. Mrs. Peters was the only defense witness to testify on this critical issue, and the appellate court found that her testimony had been more damning than helpful in sustaining their burden. She said that, before she and her husband purchased the property, she walked it on one occasion with their realtor. At that time, she specifically asked about the boundary lines but the realtor couldn’t answer her question with any certainty. She said she told her husband of the realtor’s uncertainty when they later walked the property together. She also candidly admitted that no steps were taken to obtain a survey or consult the map referenced in their deed before clearing the land. The Court found it significant that, although he had logged the property, Mr. Peters never testified. It found plenty of evidence that the defendants had no cause to know whether the land Mr. Peters was logging belonged to them or not.