Case of the Day – Monday, June 2, 2014

FOOL FOR A CLIENT

Abe Lincoln could have been talking about Mr. Victor, who has a real dummy for a client.

Ol’ Abe Lincoln was right: Mr. Victor had a first-class knucklehead for a client.The old lawyer’s proverb warns that “The man who is his own lawyer has a fool for a client.” Today’s case from Iowa puts meat on those bones.

Mr. Victor’s car was hit by a truck at an intersection. That kind of thing happens on a daily basis. After the crash, he took matters into his own hands. That does not.

Usually, people use lawyers for that kind of thing. In fact, lawyers usually take cases like this one on a contingency basis, meaning that they don’t get paid unless you win. Of course, lawyers tend to be picky about the kinds of personal injury actions they will bring, , for the same reason that more people bet on the horse “California Chrome” than lay money down on “Old Glue Factory.” Who wants to waste time and money.

Maybe Mr. Victor didn’t like lawyers. Maybe (as is more likely), no attorney would touch the case from a remote control bunker in the Amazon rain forest. For whatever reason, Mr. Victor represented himself. Apparently subscribing to the old Vladimir Ilyich Lenin maxim, “Quality has a quantity all its own,” Mr. Victor sued the other driver, the company that owned the truck the other driver was operating, the property owner whose trees allegedly obscured the stop sign, the county for poor maintenance of the intersection, and the state for poor design of the road.

Mr. Victor did it all in federal court, no doubt because suing in federal court sounds a whole lot cooler than suing in state court. And it is, too, except for those pesky rules about jurisdiction and sovereign immunity. Guess he only skimmed those chapters in Personal Injury Law for Dummies.

By the time the Court was done, the State of Iowa was dismissed as a defendant, as was the property owner. In fact, the only defendant left was the County, which was unable to prove that its tree-trimming practices were a discretionary function. Still, Mr. Victor got pretty badly decimated, proving once again that there’s a reason trained professionals cost money – it’s because they know what they’re doing.

Victor v. Iowa, Slip Copy, 1999 WL 34805679 (N.D. Iowa, 1999). A car driven by Martin L. Victor collided with a truck driven by Ronald Swoboda and owned by the Vulcraft Carrier Corp. The accident happened at the intersection of County Road C-38 and U.S. Highway 75. Then the fireworks started.

Victor, acting as his own lawyer, sued the State of Iowa, Plymouth County, Vulcraft and Elwayne Maser in U.S. District Court, apparently alleging (1) that “Iowa law regarding the right to sue private property owners for negligence is unconstitutional;” (2) that Victor should be allowed to sue Maser for acting negligently in failing to trim vegetation that obstructed his view of southbound traffic on U.S. Highway 75; (3) that the State of Iowa and Plymouth County acted negligently by failing to properly maintain a roadway, investigate the accident thoroughly, and place warning signs and markings appropriately; (4) that the highway patrol failed “to perform duties of safety officers, in assessment of dangerous conditions existing;” and (5) that Vulcraft is responsible for its driver’s failure to follow safety standards for commercial trucking. All the defendants moved to dismiss or for summary judgment.

Held: The State of Iowa was dismissed, because the Iowa Tort Claims Act, which gives permission to residents to sue the State, limits those actions to state court. The Court held that the 11th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution barred actions in federal courts against States except under narrow exceptions. One of those is that the State have given a waiver and consent that is clear and express that it has waived sovereign immunity and consented to suit against it in federal court. Although a State’s general waiver of sovereign immunity may subject it to suit in state court, it is not enough to waive the immunity guaranteed by the Eleventh Amendment. In order for a state statute or constitutional provision to constitute a waiver of Eleventh Amendment immunity, it must specify the State’s intention to subject itself to suit in federal court, and the ITCA does not do so. Therefore, Victor’s claims against the State of Iowa was dismissed.

As for the property owner Maser, the Court ruled that Iowa law put no duty on a private property owner to remove trees which obstructed the view of a highway. Although Victor claimed the Iowa law on the matter unconstitutionally deprived him of the right to sue, he never explained why. The Court observed that “while mindful of its duty to construe pro se complaints liberally, it is not the job of the court to ‘construct arguments or theories for the plaintiff in the absence of any discussion of those issues’… Besides the bare assertion that the Iowa law is unconstitutional, Victor has provided no other discussion of the issue.” Thus, the property owner Maser was dismissed as a defendant.

Victor’s claims that Plymouth County was negligent in failing to install proper warning signs and cut tree branches that obstructed his were not dismissed at this point. Section 670.4 of the Iowa Code exempts a municipality such as Plymouth County from liability for discretionary functions, if the action is a matter of choice for the acting employee, and — when the challenged conduct does involve an element of judgment — the judgment is of the kind that the discretionary function exception was designed to shield. Here, Plymouth County’s policy directed that employees “may trim branches of trees because the trees may constitute an obstruction to vision of oncoming traffic at an intersection,” thus giving employees discretion in implementation of this policy. Thus, the Court said, “the action (or inaction) of which Victor complains was a matter of choice for the county’s employee.”

However, the Court said, Plymouth County’s policy did not encompass “social, economic, and political considerations” and therefore the discretionary function exception does not apply. Victor could proceed with rebutting the County’s claim that the view was not obstructed.

Case of the Day – Tuesday, June 3, 2014

UNSNARLING DUTIES

When negligence rears its ugly head, compensation usually depends on the extent of the duty owed the victim by the party whose pocket the injured plaintiff seeks to pick. Take Tim Jones, an experienced cable television installer. One cold day in the bleak midwinter, he climbed an Indiana Bell pole to work on a cable installation. On the way down, he grabbed a phone line instead of a ladder rung. Not being intended as a support structure, the line gave way, and down Mr. Jones went.

When negligence rears its ugly head, compensation usually depends on the extent of the duty owed the victim by the party whose pocket the injured plaintiff seeks to pick. Take Tim Jones, an experienced cable television installer. One cold day in the bleak midwinter, he climbed an Indiana Bell pole to work on a cable installation. On the way down, he grabbed a phone line instead of a ladder rung. Not being intended as a support structure, the line gave way, and down Mr. Jones went.

Having no evidence that Indiana Bell knew the line was defective and likely to fall away from the pole, Mr. Jones did the only thing he could do – he sued anyway. The issue was a little daunting, because Indiana Bell hadn’t ever hired Mr. Jones. Instead, it just rented pole space to the cable company, which in turn hired the company that employed Jones. So what duty did the telephone company owe Jones in this totem-pole relationship?

Not that much of one, as it turned out. Mr. Jones lost his case, but the Court of Appeals took the opportunity to clarify the duty an easement holder has to invitees on the easement. The lesson is one that a utility holding an easement for, say, power lines, might owe to the employee of a tree-trimming service brought in to keep the easement clear of vegetation.

Jones v. Indiana Bell Telephone Co., 854 N.E.2d 1125 (Ind.App., 2007). Timothy Jones was doing a cable equipment upgrade for Sentry Cable, a cable TV provider. Jones – who had been doing this type of work for about twenty years and was aware of the associated dangers – was working as a subcontractor on this project. He was wearing the appropriate safety equipment.

The plucky old Field Marshal might have been Jones’ lawyer in this case … but the legal attack on the easement holder failed nonetheless.

Jones climbed a telephone pole owned by Indiana Bell, in order to access the cable TV line, which was located about a foot above the telephone line. On his way down, he grabbed the telephone line like it was a ladder rung. It wasn’t. It broke free, and Jones fell 20 feet to the ground, breaking his ankle. Jones sued the phone company for negligence.

At trial, Jones admitted he hadn’t observed any problems with either the telephone line or the clamp assembly. He also admitted he had no evidence that Indiana Bell knew that there was anything wrong with the pole, telephone line, or clamp assembly. Indiana Bell moved for judgment “based upon the … absence of any evidence of a breach of duty as the duty is established in Indiana law.” The trial court found Indiana Bell had no duty to Jones, and granted judgment to the phone company.

Jones appealed.

Held: Indiana Bell owed Jones nothing.

The Court observed that to prevail on a theory of negligence, Jones had to show Indiana Bell owed him a duty, it breached the duty, and his injuries were caused by the breach. Whether a defendant owes a duty of care to a plaintiff is a question of law for the court to decide. Whether an act or omission is a breach of one’s duty is generally a question of fact for the jury, but it can be a question of law where the facts are undisputed and only a single inference can be drawn from those facts.

The parties and the Court focused on the Indiana Supreme Court’s opinion in Sowers v. Tri-County Telephone Co., 546 N.E.2d 836 (Sup.Ct. Ind. 1989), which involved a telephone utility, the employee of an independent contractor, and a discussion of both duty and breach. In Sowers, the telephone company hired Covered Bridge Tree Service to trim trees located near its telephone lines and clear a right of way in order to ease the work of crews mounting cable television lines on the same poles. While trimming trees, a Covered Bridge employee fell into an abandoned manhole.

The phone company did not own the land on which the manhole was located, but it had a prescriptive easement on the land. Sowers sued Tri-County for negligence, and the trial court granted summary judgment in favor of Tri-County. The Sowers court held that a landowner or occupier is under a duty to exercise reasonable care for the protection of business invitees and that the employees of independent contractors are business invitees. The court held that Tri-County did not have a duty to inspect and warn and that the boundaries of Tri-County’s duty of reasonable care to its business invitees “must be defined from the utility’s own use of the easement.”

The phone company did not own the land on which the manhole was located, but it had a prescriptive easement on the land. Sowers sued Tri-County for negligence, and the trial court granted summary judgment in favor of Tri-County. The Sowers court held that a landowner or occupier is under a duty to exercise reasonable care for the protection of business invitees and that the employees of independent contractors are business invitees. The court held that Tri-County did not have a duty to inspect and warn and that the boundaries of Tri-County’s duty of reasonable care to its business invitees “must be defined from the utility’s own use of the easement.”

But here, the Court said, the facts of Sowers were distinguishable. There, the telephone utility itself hired the tree service company, whose employee was then injured while on the telephone utility’s easement. Here, Indiana Bell just rented space on its telephone poles to the cable company, whose subcontractor was then injured on Indiana Bell’s telephone pole. Still, the Court said, the policy reasons articulated in Sowers apply to this case, making the duties owed the same. Sowers first acknowledged that a telephone utility is a special breed in that it is not a traditional landowner or occupier. In addition, it acknowledged that a telephone utility does not often access its property except for the occasional necessity to effect repairs. Because of these facts, Sowers concluded that a great burden would be placed on a telephone utility if it were required to conduct regular inspections of its property for the sole purpose of discovering possible hazards.

Applying Sowers here, the Court concluded, Indiana Bell owed a duty of reasonable care to its invitees – including Jones – but the duty did not include the duty to inspect and warn. However, to the extent that Indiana Bell learned of dangerous conditions on its poles, it had a duty to warn its invitees. The evidence did not show Indiana Bell had any actual knowledge of the dangerous condition, meaning that the trial court properly entered judgment on the evidence in favor of Indiana Bell.

Case of the Day – Wednesday, June 4, 2014

OOPSIE!

“We’re sorry, so sorry …” Just warmin’ up for today’s case on mutual mistake. It all started with a barren cow with a fancy name, Rose 2nd of Aberlour (popularly mislabeled as “Aberlone”), in the case of Sherwood v. Walker, the classic case on mutual mistake in contract law. And the doctrine’s alive and well.

“We’re sorry, so sorry …” Just warmin’ up for today’s case on mutual mistake. It all started with a barren cow with a fancy name, Rose 2nd of Aberlour (popularly mislabeled as “Aberlone”), in the case of Sherwood v. Walker, the classic case on mutual mistake in contract law. And the doctrine’s alive and well.

In today’s Ohio decision, Mr. Thomas entered into an easement with Ohio Power to let the company string lines across his place to service his neighbor’s new house. But it turned out the house was in another power company’s service area, something no one figured out until after Ohio Power had sliced up Mr. Thomas’s trees. Thomas sued Ohio Power to rescind the easement and for damages, claiming mutual mistake. The trial court disagreed, but the Court of Appeals threw out the easement.

The Court’s most important point was this: maybe Thomas and his neighbor Baker didn’t know where the electric service boundary lay. But after all, they weren’t in the power binness. Why should they know? Ohio Power, on the other hand, was just plain sloppy in not recognizing the problem. In Court-speak, “the equities of this situation show that Ohio Power, as the company in the business of providing electric power, was in a much better position than the Thomases to discover the mistake.”

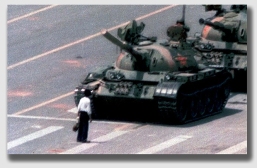

One very brave guy, but one whose read of his government was badly mistaken … if of course this ever happened, which the Chinese deny.

In order to provide grounds to rescind (undo) a contract, the mistake must be mutual. The Battle of New Orleans was a mutual mistake – Andy Jackson thought we were at war with the British, and British Admiral Thomas Cochrane thought they were still at war with the U.S. Tiananmen Square, on the other hand – which happened 25 years ago today unless you’re in China (in which case it never happened at all) – was not mutual mistake. The protesters thought the government would never massacre them for demanding more personal freedom; the government knew better.

Thomas v. Ohio Power Co., Slip Copy, 2007 WL 2892029, 2007 -Ohio- 5350 (Ct.App. Ohio, Sept. 27, 2007). The Thomases owned 159 acres of property in Augusta Township. Right next door was land owned by Brent Baker. The Thomas property is within the geographical area served by Ohio Power Company, but the Baker property is served by Carroll Rural Electric Power. Neither of the power companies may provide power to the area assigned to the other without the consent of both companies and the affected customer.

Baker asked Thomas for permission for Ohio Power to take an easement across the Thomas property to bring power to a house Baker planned to build. Thomas agreed. As a result, an easement was executed, and Ohio Power — in reliance on the easement — cut and cleared many trees on the Thomas property and along the neighboring road. But then Baker found out the house wasn’t in the Ohio Power service area, and the other power company wouldn’t permit Ohio Power to provide service to him, frustrating the purpose for the easement. The Thomases sued Ohio Power, seeking rescission of the easement contract and damages. The trial court concluded that the easement was valid and, therefore, not subject to rescission.

The Thomases appealed.

Rose, not barren at all, was worth about 12 times what farmer Sherwood sold her for.

Held: The parties had made a mutual mistake, and the contract should be rescinded. Mutual mistake is grounds for rescission of a contract if there is a mistake made by both parties as to a material part of the contract, and where the party complaining is not negligent in failing to discover the mistake. A mistake is material to a contract when it is “a mistake … as to a basic assumption on which the contract was made [that] has a material effect on the agreed exchange of performances.” Thus, the intention of the parties must have been frustrated by the mutual mistake.”

In order to claim mutual mistake as a basis for rescinding a contract, a complaint must allege (1) the existence of a contract; (2) a material mutual mistake by the parties when entering into the contract; and (3) no negligence in discovering the mistake on the complainant’s behalf. Here, the Court said, the purpose of the easement was to provide electric power to the Thomases’ neighbor. Both the Thomases and Ohio Power believed Ohio Power could provide electric power to that neighbor, but they were both mistaken about that fact. Ohio Power was in a better position to know that this belief was mistaken than the Thomases, and thus, the Court held, the contract should have been rescinded at the Thomases’ request.

Case of the Day – Thursday, June 5, 2014

STRAINED RESULT IN GEORGIA

Every morning, we look to the left and right as we pull onto the main street, only to stare into an ill-placed car wash sign. The First Armored Division could be rolling into town, and we couldn’t see it the M1A1s coming before they flattened our Yugo.

So every morning we wonder whether the sightline obstruction might not make someone liable to our next of kin when the inevitable happens. As it did one rainy night in Georgia.

A car had a chance encounter with a dump truck at a Georgia intersection. The pickup driver perished. Investigators suspected that untrimmed shrubs on vacant property at one corner of the crossroads, as well as a “curvature” in the road, made the intersection dangerous. The intersection had experienced several other accidents due to visibility.

In the aftermath of the tragic auto accident, the victim’s survivors sued the Georgia Department of Transportation, claiming it had a duty to keep trees and shrubs from a vacant lot trimmed back to protect the sight lines at the intersection in question. The trial court disagreed.

In the aftermath of the tragic auto accident, the victim’s survivors sued the Georgia Department of Transportation, claiming it had a duty to keep trees and shrubs from a vacant lot trimmed back to protect the sight lines at the intersection in question. The trial court disagreed.

On appeal, the Court agreed that as a matter of law, DOT had no duty to maintain the intersection. But it did have a duty to inspect. It seemed that an issue of fact existed as to whether the vegetation had encroached on the highway right-of-way. But the Court discounted the plaintiff’s expert opinion that encroachment had occurred, because DOT contended it didn’t know where the right-of-way began, so who knew?

The result seems to turn summary judgment on its head, letting DOT off the hook without a trial when a real fact issue – the location of the highway right of way – remained. We were left as confused about liability afterwards as we were beforehand. And we still can’t see down the street.

Welch v. Georgia Dept. of Transp., 642 S.E.2d 913 (Ct.App. Ga., 2007). Addie D. Welch was killed when her vehicle hit a dump truck at an intersection. A policeman said the overgrown bushes on the northwest corner of the intersection contributed to the accident. A sheriff’s department investigator said overgrown shrubs on the vacant property and a “curvature” in the road combined to make the intersection dangerous. Several other accidents due to visibility had occurred previously at the intersection.

Welch’s expert witness said that a driver’s line of sight was obstructed by overgrown shrubs and trees on the northwest corner of the intersection. The expert said that the overgrowth extended two feet into the Georgia DOT right-of-way, and that DOT was responsible for maintaining the line of sight. The expert also said American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials’ (AASHTO) guidelines for that intersection require a line of sight of 430 feet. Because of the overgrown vegetation, Welch’s line of sight was between 143 and 277 feet.

After the accident, DOT employees helped remove the overgrowth. Claiming that trees and shrubs on the property adjacent to the intersection were negligently maintained and obstructed her line of sight, Welch’s estate and surviving children and grandchildren sued the Georgia DOT. DOT moved for summary judgment, arguing that state law precluded plaintiffs’ claim, or in the alternative, that plaintiffs presented no evidence that Welch’s line of sight was obstructed. The trial court granted DOT’s motion, and Welch appealed.

After the accident, DOT employees helped remove the overgrowth. Claiming that trees and shrubs on the property adjacent to the intersection were negligently maintained and obstructed her line of sight, Welch’s estate and surviving children and grandchildren sued the Georgia DOT. DOT moved for summary judgment, arguing that state law precluded plaintiffs’ claim, or in the alternative, that plaintiffs presented no evidence that Welch’s line of sight was obstructed. The trial court granted DOT’s motion, and Welch appealed.

Held: DOT was not liable. The Court ruled that DOT was immune under OCGA § 32-2-2. That statute gives DOT has the general responsibility to design, manage and improve the state highway system. But, where state highways are within city limits, the DOT is required to provide only substantial maintenance and operation, such as reconstruction and resurfacing, reconstruction of bridges, erection and maintenance of official department signs, painting of striping and pavement delineators and other major maintenance activities.

Although the road Welch was on was a state highway, the intersection lay within the corporate limits of Quitman. Accordingly, DOT was required only to provide substantial maintenance activities and operations. Those activities, the Court said, did not include the maintenance of shrubbery and vegetation. Thus, the statute did not impose a duty on DOT to maintain the shrubbery. But Welch also argued that another statute, OCGA §50-21-24(8), made DOT liable for failing to inspect its right-of-way. In order to prevail on this claim, the Court said, Welch had to show that the vegetation extended into DOT’s right-of-way. DOT argues that the overgrowth was on private property.

Although Welch’s expert believed the vegetation encroached on the DOT right-of-way, the Court agreed with DOT’s view that the extent of the right-of-way couldn’t be ascertained without using courthouse records and surveyors. Because Welch’s expert had not relied on DOT testimony to opine that vegetation extended into the right-of-way, and the Court found that the evidence was uncertain as to the location of the right-of-way, Welch’s expert’s opinion that vegetation extended into the right-of-way was disregarded, and plaintiff was found not to have established DOT’s liability.

Case of the Day – Friday, June 6, 2014

LIS BLUDGEONS

If you’re suing a neighbor because you claim title to a piece of her property, the last thing you want to see happen is for her to sell it to the Sisters of the Poor before your lawsuit is completed. The neighbor makes off with the money from selling your property, and when you finally win, you have the PR problem of the bailiff dragging a gaggle of nuns off your land while TV crews report your heartlessness live on CNN.

If you’re suing a neighbor because you claim title to a piece of her property, the last thing you want to see happen is for her to sell it to the Sisters of the Poor before your lawsuit is completed. The neighbor makes off with the money from selling your property, and when you finally win, you have the PR problem of the bailiff dragging a gaggle of nuns off your land while TV crews report your heartlessness live on CNN.

It was for precisely this reason — well, maybe not precisely this reason — that the law has a mechanism known as lis pendens. A lis pendens — literally, “lawsuit pending” – is a notice filed with the office of the county responsible for deeds (often the county recorder) that puts the world on notice that litigation is going on that relates to ownership of the piece of land at issue. Practically speaking, the filing will send prospective buyers and lenders fleeing for the next county.

The purpose of lis pendens is laudable: it keeps wily defendants from transferring interests in land subject to a lawsuit, so a plaintiff doesn’t have to endlessly sue new buyers and lessees in ordercollect on a judgment. But like with any reasonable and necessary mechanism, there are those who — as the legendary trickster Dick Tuck would have said — who want to run it into the ground.

In today’s case, the plaintiff sued the defendant over a large tree on the boundary between their properties, alleging that it had been negligently trimmed to lean onto their property, that it constituted a “spite fence,” and that its size and location constituted a nuisance. Of interest to us was the last allegation, that in a prior lawsuit between the parties, the defendant’s lawyer had filed a lis pendens on plaintiff’s lot that caused a sale to fall through. The plaintiffs said that the lis pendens — which a court had later thrown out — constituted a tort known as “slander of title.” This was so because the underlying litigation had nothing to do with whether the defendant claimed title or the right to possess the plaintiff’s property. Defendant’s lawyer filed it simply as a club with which to bludgeon the plaintiffs, as part of a take-no-prisoners litigation strategy.

The defendant’s lawyer argued the slander of title had to be dismissed, because as counsel for the other side, he owed no duty to the plaintiffs. The California court conceded that he didn’t, but said that was irrelevant: slander of title is an intentional tort (like a judge hauling off and slugging a public defender). Unfortunately, the Court said, the plaintiffs’ pleading wasn’t very well written, and the Court couldn’t be sure that they had alleged malice. The more prudent course, the Court thought, was to offer them a chance to amend their complaint to make clear that they were alleging the defendant’s attorney had acted maliciously.

The defendant’s lawyer argued the slander of title had to be dismissed, because as counsel for the other side, he owed no duty to the plaintiffs. The California court conceded that he didn’t, but said that was irrelevant: slander of title is an intentional tort (like a judge hauling off and slugging a public defender). Unfortunately, the Court said, the plaintiffs’ pleading wasn’t very well written, and the Court couldn’t be sure that they had alleged malice. The more prudent course, the Court thought, was to offer them a chance to amend their complaint to make clear that they were alleging the defendant’s attorney had acted maliciously.

Castelanelli v. Becker, Not Reported in Cal.Rptr.3d, 2008 WL 101729 (Cal.App, Jan. 10, 2008). The Castelanellis own real estate in Humboldt County. They sued the owner of the neighboring home, Kristine Mooney, and her lawyer Thomas Becker, alleging that on the border between their unimproved lot and Mooney’s property, “a large tree” curves from the bottom portion of its trunk toward the Castelanellis’ property and takes up so much space that “the subject property cannot reasonably be developed as a residential property.” They also claimed that Mooney’s house tree blocked light to the tree and caused the tree to grow almost exclusively over their property, and that Mooney had trimmed or negligently maintained the tree to contribute to its “odd and unusual angle.”

The complaint maintained that the tree constituted a spite fence within the meaning of California law, and was “maliciously maintained for the purpose of annoying the plaintiffs and in an attempt to gain ownership of plaintiffs’ land at less than fair value.” The complaint alleged nuisance, trespass, tortious interference with contractual relations, and tortious interference with economic relations. The Castelanellis alleged that Mooney sought to “purchase plaintiffs’ property at below fair market value” and had “threatened legal action if plaintiffs trimmed the subject tree in order to make their property capable of being developed and sold.” Finally, they alleged that Mooney and Becker published “false statements” in a lis pendens filed as to the Castelanellis’ property, and this lis pendens — later thrown out by another court — had prevented the Castelanellis from selling the property. The trial court agreed that because Mooney and Becker owed the Castelanellis no duty, there could be no slander.

The Castelanellis appealed.

Held: The Castelanellis had made out an adequate cause of action against Attorney Becker. A party to an action who asserts a real property claim may record a notice of pendency of action in which that real property claim is alleged, called a lis pendens. Such a notice places a cloud on the title, and effectively keeps any willing buyer from wanting to close on a transaction until the lis pendens is cleared. In order to be privileged, so that no party may later sue a party or its attorney for filing such a notice, a notice of lis pendens must both (1) identify a specific action “previously filed” with a superior court and (2) show that the previously-filed action affects “the title or right of possession of real property.

In this case, the notice of lis pendens clearly identified that it was signed and filed in conjunction with litigation involving a tree growing upon a shared property line. But nothing in the record enabled the Court to determine that litigation involved the “right of possession” of either of the two properties involved in that litigation. If it did, a litigation privilege clearly applied, and the action against Attorney Becker could not stand.

Becker argued that he had no duty to the Castelanellis, and he could therefore not be sued by them. The Court pointed out that this would be true if the action were based on negligence. However, the action was an intentional tort, like the tort of malicious prosecution, and there need not be a duty of care owed to the victim by the perpetrator before an intentional tort can be inflicted. The Court said that while an attorney cannot be liable in negligence to a formerly adverse party, that rule does not exempt the attorney from liability for malicious prosecution.

The tort of slander of title does not rise to the level of either malicious prosecution or abuse of process. The elements of the tort have traditionally been held to be publication, falsity, absence of privilege, and disparagement of another’s land which is relied upon by a third party and results in a pecuniary loss. Slander of title does not include express malice as an intrinsic factor. Here, while the Castelanellis did not specifically plead malicious prosecution in their amended complaint, that complaint does include allegations that the actions “were done knowingly, willfully, and with malicious intent.” The allegations seemed to the Court sufficient to inject into the slander of title cause of action an allegation of malice, even as to attorney Becker.

In any event, the Court said, the law is clear that, in evaluating a complaint against a general demurrer, it is not necessary that the cause of action be the one intended by plaintiff. The test is whether the complaint states any valid claim entitling plaintiff to relief. Thus, plaintiff may be mistaken as to the nature of the case, or the legal theory on which he or she can prevail. But if the essential facts of some valid cause of action is alleged, the complaint is good against a general demurrer.

In any event, the Court said, the law is clear that, in evaluating a complaint against a general demurrer, it is not necessary that the cause of action be the one intended by plaintiff. The test is whether the complaint states any valid claim entitling plaintiff to relief. Thus, plaintiff may be mistaken as to the nature of the case, or the legal theory on which he or she can prevail. But if the essential facts of some valid cause of action is alleged, the complaint is good against a general demurrer.

The Court held that the absence of any suggestion in the Castelanellis’ opposition to Becker’s demurrer that they either wished to amend or intended to plead some sort of intentional tort via their fifth cause of action left the Court reluctant to rule that the trial court abused its discretion by sustaining the demurrer without leave to amend. Under all the circumstances, the Court thought the better course of action was to remand this matter to the trial court with instructions to consider whether any intentional tort — as distinguished from a claim of negligence — was in fact pled by the Castelanellis and (2) if not, whether the Castelanellis wish to and can plead a valid intentional tort cause of action against Becker regarding the allegedly improper lis pendens.

Case of the Day – Monday, June 9, 2014

CHUTZPAH, CONNECTICUT STYLE

So you like your wild mountain property, with its clean, sparkling streams and majestic trees? You like to think that it will always look as pristine and undeveloped as it does right now. To make certain, when you finally sell it, you place some restrictions on the deed, so that there won’t be any double-wide trailers, pre-fab A-frame chalets or tar paper shanties.

“God Bless Our Home” – why the seller of the property preferred some lousy forest and lake over a beautiful home with nice attached garage still baffles us …

Seems reasonable, doesn’t it? But eventually the people you sold the land to sell it to someone else, and the someone else has a really good lawyer. “This is Connecticut!” the solicitor tells his client. “We can beat this restriction!”

And lo and behold, that’s just what he does. It seems in Connecticut, the terms on which you were originally willing to sell your land don’t much matter. In today’s case, the heirs of the original nature-lovin’ owner suffered a lot of angst when they finally sold off most of the lake property. But the buyer won them over, even agreeing to a development restriction on part of the land, in order to preserve its natural character. A few years later, that buyer sold the land to the Williams, who had been convinced by their lawyer that the restriction wasn’t enforceable. The new owners promptly sued for a declaratory judgment that the restriction was void.

The Connecticut court agreed that it was. It fell outside of the three traditional categories of restrictions that ran with the land. Even so, the Court said, it could be enforced under equitable principles. But it wouldn’t do that, the Court said, because it would be so unfair to the buyers of the land. After all, the Court said, it wasn’t clear who the beneficiary of the restriction was or who could enforce it. Therefore, the Court held it would be unfair to the buyers because — and we’re not making this up — they “bought the property because they thought the restriction was unenforceable. If the restriction is found enforceable, the property could only be developed for recreational purposes and would be far less valuable. Devaluing property without a clear beneficiary is not reasonable.”

The decision certainly turns common sense on its head. Where a seller is unwilling to sell unless a restriction is placed on the land, it’s hard to argue that the continuing restriction harms marketability. It’s more marketable than if the seller doesn’t sell at all. And for that matter, should it be the law’s business to promote marketability over a seller’s free will?

It seems safe to imagine that as conservation — and especially forest preservation because of “climate change” concerns — is of increased public policy importance, the notion of “marketability” and the free right to develop may become less of a holy grail. As it probably should.

Williams v. Almquist, 2007 WL 3380299 (Conn. Super., Oct. 30, 2007) (unreported). Robert Bonynge bought a 150-acre tract of land at Lake Waramaug in 1898, which he later conveyed away in several parcels. Although some of the original tract was sold in the 1930s, and some of the heirs owned certain parcels outright, a 105-acre tract was eventually sold to Lee and Cynthia Vance by the Bonynge heirs in 2001. The negotiations for that sale were a difficult and emotional process, with the primary concern of the heirs to conserve the natural condition of the property. The Vances agreed to give some of the land and a conservation easement to the Weantinoge Heritage Land Trust. Also, they agreed a restriction on 8.9 acres of the property: “There shall be no construction or placing of any residential or commercial buildings upon this property provided that non-residential structures of less than 400 square feet may be constructed for recreational or other non-residential purposes and further provided that the property may be used for passive activities such as the installation of septic and water installations, the construction of tennis courts, swimming pools and the construction of facilities for other recreational uses.”

David and Kelly Williams bought part of the 8.9-acre tract in 2005 from the Vances, still still subject to the restriction agreed upon in February 2002. Shortly thereafter, the Williams entered into an agreement with the Vances in which the Vances waived their right to enforce the restriction. The Williams then sued for declaratory judgment against the Bonynge heirs, asking the court to declare the restriction in their deed void and unenforceable.

Held: The restriction on the Williams’ land is unenforceable. The Court noted that restrictive covenants generally fall into one of three categories: (1) mutual covenants in deeds exchanged by adjoining landowners; (2) uniform covenants contained in deeds executed by the owner of property who is dividing his property into building lots under a general development scheme; and (3) covenants exacted by a grantor from his grantee presumptively or actually for his benefit and protection of his adjoining land which he retains. Here, the restrictive covenant did not fall under the first category because it originally arose from the sale of the Bonynge heirs’ land to the Vances, not from an exchange of covenants between adjoining landowners. Likewise, the second category did not apply. Rather, that category applies under a general developmental scheme, where the owner of property divides it into building lots to be sold by deeds containing substantially uniform restrictions, any grantee may enforce the restrictions against any other grantee. But in this case, the Court ruled, the evidence suggested that a common plan or scheme did not exist.

The restrictive covenant did not fall under the third category either. Where the owner of two adjacent parcels conveys one with a restrictive covenant and retains the other, whether the grantor’s successor in title can enforce, or release, the covenant depends on whether the covenant was made for the benefit of the land retained by the grantor in the deed containing the covenant, and the answer to that question is to be sought in the intention of the parties to the covenant expressed therein, read in light of the circumstances attending the transaction and the object of the grant. The question of intent is determined pursuant to the broader principle that a right to enforce a restriction of this kind will not be inferred to be personal when it can fairly be construed to be appurtenant to the land, and that it will generally be construed to have been intended for the benefit of the land, since in most cases it could obviously have no other purpose, the benefit to the grantor being usually a benefit to him as owner of the land, and that, if the adjoining land retained by the grantor is benefitted by the restriction, it will be presumed that it was so intended. Here, three of the Bonynge heirs retained property near the 105-acre tract, but did not own property directly adjoining or overlooking the restricted tract. As such, the Court said, there was no presumption that the restriction was meant to benefit their land. The deed didn’t say as much: in fact, the deed didn’t indicate that the restriction was meant to benefit anyone at all. With no mention of beneficiaries in the deed and no testimony regarding the intent of the retaining landowners, the Court held, the restriction could not fall under the third category.

The restrictive covenant did not fall under the third category either. Where the owner of two adjacent parcels conveys one with a restrictive covenant and retains the other, whether the grantor’s successor in title can enforce, or release, the covenant depends on whether the covenant was made for the benefit of the land retained by the grantor in the deed containing the covenant, and the answer to that question is to be sought in the intention of the parties to the covenant expressed therein, read in light of the circumstances attending the transaction and the object of the grant. The question of intent is determined pursuant to the broader principle that a right to enforce a restriction of this kind will not be inferred to be personal when it can fairly be construed to be appurtenant to the land, and that it will generally be construed to have been intended for the benefit of the land, since in most cases it could obviously have no other purpose, the benefit to the grantor being usually a benefit to him as owner of the land, and that, if the adjoining land retained by the grantor is benefitted by the restriction, it will be presumed that it was so intended. Here, three of the Bonynge heirs retained property near the 105-acre tract, but did not own property directly adjoining or overlooking the restricted tract. As such, the Court said, there was no presumption that the restriction was meant to benefit their land. The deed didn’t say as much: in fact, the deed didn’t indicate that the restriction was meant to benefit anyone at all. With no mention of beneficiaries in the deed and no testimony regarding the intent of the retaining landowners, the Court held, the restriction could not fall under the third category.

The trial court said it could properly consider equitable principles in rendering its judgment, consistent with Connecticut’s position favoring liberal construction of the declaratory judgment statute in order to effectuate its sound social purpose.

Some might argue that maintaining the forest as a carbon sink was a worthwhile social purpose

Although courts before have approved restrictive covenants where they benefited a discernable third party, the Court here found that the restriction was not reasonable because it had no clear beneficiary and limited the marketability of the property. The possible beneficiaries were the Bonynge heirs, only those heirs who retained property in the Lake Waramaug area, the other residents in the Lake Waramaug area, the Vances, or simply nature itself. Without a discernible beneficiary, the Court ruled, it was difficult to determine who could enforce the restriction and for how long.

The restriction also unreasonably limited the marketability of the property. Although restrictions are often disfavored by the law and limited in their implication, restrictive covenants arose in equity as a means to protect the value of property. Here, no identifiable property was being protected by the restriction. The plaintiffs bought the property because they thought the restriction was unenforceable. If the restriction is found enforceable, the property could only be developed for recreational purposes and would be far less valuable. Devaluing property without a clear beneficiary, the Court said, was not reasonable.

Case of the Day – Tuesday, June 10, 2014

BOUNDARY TREES BELONG TO US ALL

Don’t start singing “We are the World” just yet, but trees that grow on the boundaries between properties generally belong to us all, at least all of us who own the properties on which the tree sits. That’s the general law … but not in Colorado.

In today’s case, the Rhodigs loved the trees planted along the property line. They cared for them, added to the tree line, and even replaced one when it died. You know what happens when trees grow. They get bigger, a botanical phenomenon that is beyond the scope of this blog. But trust us on this. Over a 20-year period, these particular trees grew so they finally stood astride the boundary line of the properties. One, due to a slight miscalculation on the Rhodigs’ part, was entirely (but very slightly) on the neighbors’ land.

At least that’s where they stood until Mr. Keck moved in and cut them down. The Rhodigs sued, claiming the trees that grew on both properties were owned as tenants in common. This was important, because the traditional rule was that in such a case, neither party could cut down a tree without the consent of the other. The Supreme Court of Colorado held that whether the trees grew on the boundary wasn’t as important as what had been the agreement between the parties when the trees were planted. There has to be meeting of the minds as to the planting, the care, or even the purpose of the trees, the Court said, because without an agreement, one party cannot have an ownership interest in something affixed to someone else’s land.

At least that’s where they stood until Mr. Keck moved in and cut them down. The Rhodigs sued, claiming the trees that grew on both properties were owned as tenants in common. This was important, because the traditional rule was that in such a case, neither party could cut down a tree without the consent of the other. The Supreme Court of Colorado held that whether the trees grew on the boundary wasn’t as important as what had been the agreement between the parties when the trees were planted. There has to be meeting of the minds as to the planting, the care, or even the purpose of the trees, the Court said, because without an agreement, one party cannot have an ownership interest in something affixed to someone else’s land.

A spirited dissent argued the traditional English rule — that held that trees straddling a boundary belonged to both parties as tenants in common — makes more sense. Certainly, it saves a lot of judicial hair-splitting as to agreements and courses of dealing between two neighbors who were now in court.

Rhodig v. Keck, 161 Colo. 337, 421 P.2d 729, 26 A.L.R.3d 1367 (Sup.Ct. Colo. 1966). The Rhodigs sued Roy Keck for malicious and wanton destruction of four trees which allegedly grew on the boundary line between the Rhodig and Keck properties. Keck admitted removing the trees but alleged that they were completely on his property and that he had the right to destroy them.

When the Rhodigs purchased their property, there were two trees standing near the lot line. In 1943 Rhodig planted two more trees in a line with the first two. Later one of the original trees died and the Rhodigs replaced it. In 1962 Keck, wishing to fence his property to the south of Rhodigs, had a survey made of the lot line. This showed that one tree was entirely inside Keck’s property by three inches; a second tree, 18 inches in diameter, extended four inches onto Rhodigs’ land and was 14 inches on Keck’s lot; a third tree, eight inches in diameter, extended two inches onto Rhodigs’ land and was six inches on Keck’s lot; the fourth tree, which was 16 inches in diameter, was growing five inches on Rhodigs’ land and 11 inches on Keck’s lot.

As a result of the survey, Keck removed the trees. Incidentally, the Rhodigs had done their own survey 10 years earlier, and their findings matched those of Mr. Keck. In fact, they had tried to buy a strip of land with the trees from Mr. Keck without success.

The trial court granted Keck’s motion to dismiss at the close of plaintiffs’ case, finding that the Rhodigs had failed to establish that they were owners of the trees. The Rhodigs appealed.

Held: The Court held that the Rhodigs’ contention that they and Keck were tenants in common of the trees did not hold. It said “the trees in question, when planted, must necessarily have been wholly upon Keck’s property and no agreement or consent was shown concerning ownership. The mere fact that the Rhodigs testified that they owned the trees and maintained them is not sufficient evidence to permit a recovery. This is so because they could not own something affixed to Keck’s land without some agreement, right, estoppel or waiver. Apparently a test in determining whether trees are boundary line subjects entitled to protection is whether they were planted jointly, or jointly cared for, or were treated as a partition between adjoining properties. In the instant case none of these attributes was proved by the plaintiffs.”

Held: The Court held that the Rhodigs’ contention that they and Keck were tenants in common of the trees did not hold. It said “the trees in question, when planted, must necessarily have been wholly upon Keck’s property and no agreement or consent was shown concerning ownership. The mere fact that the Rhodigs testified that they owned the trees and maintained them is not sufficient evidence to permit a recovery. This is so because they could not own something affixed to Keck’s land without some agreement, right, estoppel or waiver. Apparently a test in determining whether trees are boundary line subjects entitled to protection is whether they were planted jointly, or jointly cared for, or were treated as a partition between adjoining properties. In the instant case none of these attributes was proved by the plaintiffs.”

The Court held that one of the trees — being wholly on Keck’s land — was not involved in the dispute at all. As to the other three trees, the Court said, the Rhodigs had failed to prove a legal or equitable interest in them, meaning that the legal owner of the land — Mr. Keck — had the right to remove the encroachment.

The judgment was affirmed.

Case of the Day – Wednesday, June 11, 2014

ALL YOUR TREE ARE BELONG TO US

If you were not following Internet culture (as oxymoronic as that phrase may be) back in 2001, you might not recognize the badly-mangled taunt “All your base are belong to us,” derived from the poorly-translated Japanese video game, Zero Wing. It became a cult classic in 2001, and the melodious strains of the techno dance hit Invasion of the Gabber Robots can be heard in some of the goofier corners of the ‘Net – and there are plenty of those – to this very day.

In today’s case, an elm tree stood on the boundary line between the Ridges and the Blahas. One can almost imagine Mr. Blaha — who was tired of the mess the elm made every fall — announcing to the tree that “you are on the way to destruction!” But the problem was that, contrary to Mr. Blaha’s belief, all the tree’s base did not belong to him, at least not just to him. Rather, the base of the tree straddled the property line between the Blaha homestead and the Ridges’ house.

In today’s case, an elm tree stood on the boundary line between the Ridges and the Blahas. One can almost imagine Mr. Blaha — who was tired of the mess the elm made every fall — announcing to the tree that “you are on the way to destruction!” But the problem was that, contrary to Mr. Blaha’s belief, all the tree’s base did not belong to him, at least not just to him. Rather, the base of the tree straddled the property line between the Blaha homestead and the Ridges’ house.

Unlike the Colorado decision of Rhodig v. Keck, which we discussed yesterday, the Illinois court did not require that the plaintiff show who had planted or cared for the tree. Instead, its analysis was simple: the tree grew in both yards, and thus, the Ridges had an interest in the tree, as did the Blahas. This made the landowners “tenants in common,” and prohibited either from damaging the tree without permission of the other.

The Illinois view, which is the more common approach that Colorado’s “husbandry” test, is the prevailing view in the United States. In this case, the Court issued an injunction against Mr. Blaha prohibiting him from cutting down the tree. For great justice.

Ridge v. Blaha, 166 Ill.App.3d 662, 520 N.E.2d 980 (Ct.App. Ill. 1988). The Ridges sought an injunction against the Blahas to prevent them from damaging an elm tree growing on the boundary line between their respective properties. After living with the elm for many years, the Blahas tired of the tree’s unwanted effects and decided to remove it with the help of an arborist. The Ridges were not consulted, however, and when arborist Berquist came to remove the tree, plaintiffs objected that the tree belonged to them and that they did not want it destroyed.

The evidence showed that the base of the tree extended about 5 inches onto the Ridges’ property, but that the tree trunk narrows as it rises so that at a height of 1.25 feet, the trunk is entirely on Blahas’ side of the line. Photographs were also introduced which showed the tree interrupting the boundary line fence. The trial court found that no substantial portion of the elm’s trunk extended onto the Ridges’ property and that, as such, they did not have a protectable ownership interest in the tree. The Ridges appealed.

The evidence showed that the base of the tree extended about 5 inches onto the Ridges’ property, but that the tree trunk narrows as it rises so that at a height of 1.25 feet, the trunk is entirely on Blahas’ side of the line. Photographs were also introduced which showed the tree interrupting the boundary line fence. The trial court found that no substantial portion of the elm’s trunk extended onto the Ridges’ property and that, as such, they did not have a protectable ownership interest in the tree. The Ridges appealed.

Held: The Ridges had a protectable interest. The Court held that the fact that a tree’s roots across the boundary line, acting alone, is insufficient to create common ownership, even though a tree thereby drives part of its nourishment from both parcels. However, where a portion of the trunk extends over the boundary line, a landowner into whose land the tree trunk extends had protectable interest even though greater portion of trunk lied on the adjoining landowners’ side of boundary. That interest makes the two landowners tenants in common, and is sufficient to permit the grant of an injunction against the adjoining landowner from removing the tree.

Case of the Day – Thursday, June 12, 2014

WHEN A TREE GROWS INTO A BOUNDARY – AND CAUSES A NUISANCE

Trees often don’t start out straddling property lines. Rather, they sprout as carefree saplings, but later grow above and below the ground without regard for metes and bounds.

Do you remember Flap Your Wings? It’s a great children’s book by P.D. Eastman, a story in which Mr. and Mrs. Bird suddenly find an oversize egg in their nest, placed there by a well-meaning stranger who found the orb on the ground and wrongly deduced it had fallen from the tree? They love and care for the egg, but it hatches into something that unexpectedly becomes a real nuisance in their nest.

When the Bergins planted a tree on their land in 1942, they had little idea that it would grow into a big problem. The tree thrived over 25 years, a great oak from a little acorn having grown. (All right, it was an elm, but you take the point …) It expanded from its modest plot toward and across the boundary line with their neighbors, in the process knocking the neighbors’ chain link fence out of line, raising the sidewalk and causing drainage problems.

The Holmbergs argued that the tree was a nuisance, and demanded that the Bergins remove it. The Bergins argued that the tree was a boundary tree, and it thus belonged to both the neighbors and to them commonly. They thus could not be seen to be maintaining a nuisance.

The Court disagreed with the Bergins’ defense, ultimately adopting the rationale of the Colorado case of Rhodig v. Keck. It was the intent of the parties, the Court ruled, not the location of the tree, that governed whether the tree was a boundary tree.

Little trees don’t stay little

Here, the Bergins planted and maintained the tree exclusively. They and the Holmbergs neither treated nor intended the elm to be a boundary tree. Instead, the tree ended up straddling the boundary only by an accident of growth. No matter where the tree had grown to encompass, it remained the Bergins’ tree, and the court found it to be a nuisance.

The damage wrought by the tree makes an interesting comparison to the 2007 Virginia decision in Fancher v. Fagella on encroachment and nuisances. The tree’s shallow root system made remedies short of removal infeasible, and the roots seemed to run just about everywhere. The case is an excellent illustration of how the facts of the particular growth at issue can drive a court’s decision.

Holmberg v. Bergin, 285 Minn. 250, 172 N.W.2d 739 (Sup.Ct. Minn. 1969). The Bergins and Holmbergs were adjoining landowners in Minneapolis. In 1942, the Bergins planted an elm tree on their property about 15 inches north of the boundary line, and they have maintained the tree and have exercised sole control over it since that time. The Holmbergs bought their place 10 years later, and constructed a chain-link fence on their property 4 inches south of the common boundary line. When the fence was completed, the tree was 6 inches away from it and 2 inches away from the boundary line, so the tree did not touch or interfere with the fence.

By 1968, the tree was 75 feet high, with a trunk diameter of 2 1/2 feet, and it was protruding about 8 inches onto the Holmberg’s property. Its roots extended onto Holmberg’s property and pushed the fence out of line, making the use of a gate in the fence impossible. The tree was close to both houses and the roots, being cramped for room, have pushed up a large hump in the ground around the base of the tree. The roots raised the ground level from the base of the tree to the Holmbergs’ sidewalk and caused it to tip toward their house, resulting in drainage into their basement.

To fix the problem, the Holmbergs were forced to construct a new sidewalk, which — because of the tree roots — promptly cracked as well. The Bergins’ property value property would depreciate by $5,000 if the tree were removed.

The parties had never agreed that the tree would mark their boundary – and this was important to the court

Over the Bergin’s complaint that the tree was a boundary tree, the trial court found that the tree was a nuisance and ordered it removed by the Bergins at their own expense. No damages were awarded to the Holmbergs due to their failure to take advantage of earlier opportunities to remove roots. The Bergins appealed.

Held: The tree was a nuisance. The Minnesota Supreme Court held that something more than the mere presence of a portion of a tree trunk on a boundary line is necessary to make the tree itself a ‘boundary line tree’ so as to bring it within the legal rule that it is owned by adjoining landowners as tenants in common.

Whether the tree marks the boundary depends upon the intention, acquiescence, or agreement of the adjoining owners or upon the fact that they jointly planted the hedge or tree or jointly constructed the fence.

Nothing in the record discloses any intention of the parties that the tree mark a boundary line between the properties. The law is clear that one cannot exercise his right to plant a tree in such a manner as to invade the rights of adjoining landowners. When one brings a foreign substance on his land, he must not permit it to injure his neighbor. And, the Court held, an injunction against the continuance of a nuisance — such as the one issued by the trial court — may be proper if it is necessary to a complete and effectual abatement of the nuisance

Case of the Day – Friday, June 13, 2014

PROGRESS IN FITS AND STARTS

This is the perfect time of year to ask this, with the corn in many midwestern fields already knee-high. It’s already getting harder to remember the bleak mid winter, when the countryside looked so stark and empty. Before you know it, country roads will seem like passages cut between towering falls of corn. In many parts of the American Midwest, “corn to the corners” is the rule.

In the Midwest, farmers plant corn to the corners – good yields, but lousy sightlines

Something reminded us of sightlines yesterday. Maybe it was the rusted F-150 pickup that barely slowed going through the four-way stop intersection we were approaching. It might have been The Who, singing “I Can See For Miles and Miles” on the SiriusXM 60s station we were listening to. Whatever caused the thought, my wife wondered aloud whether the farmers who planted their corner right to the corners of the field – obscuring the sightlines for motorists approaching an intersection – might be liable for resulting collisions.

The Florida Supreme Court has wrestled with this issue, and thrashed around trying to define a standard for the liability of landowners to people not on their property for injury resulting from the conditions of the land.

Up until a few years ago, the Florida high court had adopted a “foreseeable zone of risk” test to determine whether a defendant owed a duty to a plaintiff. That test, simply put, was a judicial determination of whether it was reasonably foreseeable that some adverse condition would create a risk. This is not a ‘proximate cause’ analysis, although the casual reader would be forgiven for thinking it was. Rather, the inquiry in the “foreseeable zone of risk” test was one of a general zone of harm, such as whether overgrown foliage from private land extending over a highway would generally create a foreseeable zone of risk to motorists.

Prior to the “foreseeable zone of risk” test, the Court had employed a rather strict agrarian-era test that pretty much held a landowner blameless for any harm caused by a defect in his or her land. But under the “foreseeable zone of risk” test, the Court had held, for example, that a service station owner whose foliage had grown to obscure ingress and egress to the station was liable for damages resulting from a collision.

Then, in Williams v. Davis, the Court restored the balance. It explained that the service station owner was a commercial business in an urban area, one that specifically relied on the frequent coming and going of motor vehicles. Employing the foreseeable zone of risk analysis made sense. In the Williams case, however, the defendant was a homeowner whose bushy trees and shrubs were contained entirely on her own property. The Court employed the foreseeable zone of risk test, but found it unlikely that a residential landowner would foresee that adjacent motorists would be endangered by the mere presence of foliage on the property.

The Court’s approach isn’t particularly helpful to landowners trying to determine the extent of their duties. The service station owner probably thought he was all right under the old agrarian standard, until his case became the vanguard of the new movement. There was no reason for the defendant in this latest case to feel secure in the wake of the service station decision, but it turns out she was. The same casual reader forgiven above might be excused for wondering whether all this “foreseeable” and “unlikely” business isn’t a lot of judicial lawmaking on a case-by-case “feel” in a rump approach that makes it very difficult for a landowner to know in whose or what zone he or she might be in. Very messy.

For her part, my wife – a sweet corn lover of the first water – would hold farmers liable for stands of field corn, but not if it were Silver Queen. The standard seems irrational, but at least its not nearly as amorphous as the “foreseeable zone of risk” analysis.

Williams v. Davis, 974 So.2d 1052 (Sup.Ct. Fla., 2007). Twanda Green, an employee of Diamond Transportation Services, Inc., died in an accident while transporting cars in a procession from one rental car location to another. As she made a left-hand turn at the “T” intersection of Pine Street and Sidney Hayes Road, a dump truck ran into her car, killing her.

Her estate sued several defendants, including Beverly Williams, who owned the home and property abutting the intersection. The Estate claimed that foliage on the property obstructed Green’s view of other traffic as she approached the intersection. Williams moved for summary judgment, and the trial court agreed, throwing out the suit against the landowner. While the trial court opinion referred to “overgrown foliage” and “obstructing foliage,” nothing in the record suggested that the Estate was claiming that the foliage actually extended outside the bounds of the Williams’ land or into the right-of-way. The Court of Appeals reversed, holding that Williams owed Green and other motorists a duty of care to maintain the foliage on the property so as not to restrict the visibility of motorists at the intersection. Williams appealed to the Florida Supreme Court.

Held: A private landowner does not have a duty of care to motorists arising from trees or foliage that does not intrude into the right-of-way. The Court applied what is known in Florida as the “foreseeable zone of risk” analysis established in McCain v. Florida Power Corp. A party claiming negligence must show that the landowner owed a “duty, or obligation, recognized by the law, requiring the [landowner] to conform to a certain standard of conduct, for the protection of others against unreasonable risks.” Where a person’s conduct is such that it creates a “foreseeable zone of risk” posing a general threat of harm to others, a legal duty will ordinarily be recognized to ensure that the underlying threatening conduct is carried out reasonably.

Held: A private landowner does not have a duty of care to motorists arising from trees or foliage that does not intrude into the right-of-way. The Court applied what is known in Florida as the “foreseeable zone of risk” analysis established in McCain v. Florida Power Corp. A party claiming negligence must show that the landowner owed a “duty, or obligation, recognized by the law, requiring the [landowner] to conform to a certain standard of conduct, for the protection of others against unreasonable risks.” Where a person’s conduct is such that it creates a “foreseeable zone of risk” posing a general threat of harm to others, a legal duty will ordinarily be recognized to ensure that the underlying threatening conduct is carried out reasonably.

The McCain analysis is different from the type of foreseeability required to establish a duty as opposed to that which is required to establish proximate causation. Establishing the existence of a duty requires demonstrating that the activity at issue created a general zone of foreseeable danger of a certain type of harm to others.

By contrast, establishing proximate cause requires a factual showing that the dangerous activity foreseeably caused the specific harm suffered by those claiming injury in the pending legal action. Prior to McCain, Florida courts had followed the common law “agrarian rule” to determine whether a duty exists by landowners to motorists or others passing on a neighboring highway.

Under the agrarian rule, a landowner could never be held liable for harm occurring to motorists on adjacent roadways as a result of natural conditions on the land regardless of any alleged neglect of the landowner. That rule was developed when Florida was largely an agrarian society, and provided that a landowner was essentially immune to claims by persons not on the landowner’s property when injured, even when those persons claimed a condition on the land caused the injury. The rule was also based in part on a distinction between acts of malfeasance and nonfeasance, which reasoned that harm resulting from the mere passive existence of purely natural conditions constituted nonfeasance, whereas harm caused by the active creation of conditions would constitute malfeasance.

More recently, in Whitt v. Silverman, the Supreme Court rejected application of the absolute no-liability agrarian rule in considering whether a commercial landowner in an urban setting owed a duty to motorists and pedestrians who might be harmed by conditions on the property. Instead, it applied the “zone of risk” foreseeability analysis articulated in McCain, and concluded that under that holding, the landowners’ conduct created a foreseeable zone of risk posing a general threat of harm toward the patrons of the business as well as those pedestrians and motorists using the abutting streets and sidewalks. The decision stood for the proposition that a business may be held liable to pedestrian passers-by by reason of the failure of the business to provide safe egress to vehicles exiting the premises. But for McCain, there are no Florida decisions imposing liability upon a property owner based on natural conditions contained wholly within the boundary of the private property.

The Court recognized in this case that ordinarily a private residential landowner should be held accountable under the zone of risk analysis principles of McCain only when it can be determined that the landowner has permitted conditions on the land to extend into the public right-of-way so as to create a foreseeable hazard to traffic on the adjacent streets. Applying that test in this case, the Court saw little basis for imposing liability on the owner of a wooded residential lot for letting the property remain in its natural condition, as long as the growth did not extend beyond the property’s boundaries. Unlike the situation in Whitt, wherein it concluded that it should be foreseeable to the operator of a commercial service station that obstructions to the vision of an exiting motorist could constitute a danger to adjacent pedestrians, the Court found it unlikely that a residential landowner would foresee that adjacent motorists would be endangered by the mere presence of foliage on the property.

The Court recognized in this case that ordinarily a private residential landowner should be held accountable under the zone of risk analysis principles of McCain only when it can be determined that the landowner has permitted conditions on the land to extend into the public right-of-way so as to create a foreseeable hazard to traffic on the adjacent streets. Applying that test in this case, the Court saw little basis for imposing liability on the owner of a wooded residential lot for letting the property remain in its natural condition, as long as the growth did not extend beyond the property’s boundaries. Unlike the situation in Whitt, wherein it concluded that it should be foreseeable to the operator of a commercial service station that obstructions to the vision of an exiting motorist could constitute a danger to adjacent pedestrians, the Court found it unlikely that a residential landowner would foresee that adjacent motorists would be endangered by the mere presence of foliage on the property.

The Court said that while all property owners must remain alert to the potential that conditions on their land could have an adverse impact on adjacent motorists or others, it was not convinced the existing rules of liability established by our case law that distinguish conditions having an extra-territorial effect from those limited to the property’s boundaries should be abandoned. Furthermore, motorists in Florida have a continuing duty to use reasonable care on the roadways to avoid accidents and injury to themselves or others. That duty, the Court said, includes a responsibility to enter intersections only upon a determination that it is safe to do so under prevailing conditions.

Case of the Day – Monday, June 16, 2014

DOING NOTHING IS NOT AN OPTION

“A stitch in time saves nine” is an idiom that’s been around for three hundred years or so. It also is an everyday explanation of the equitable doctrine of “laches.”

It always seemed a little ironic that English common law needed an entire branch of jurisprudence known as “equity.” Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., famously lectured a litigant once that his courtroom was “a court of law, young man, not a court of justice.” It was precisely because there was so much law and so little justice that medieval England developed a parallel judicial system known as courts of equity, where litigants could get just results that were precluded in the courts of law by hidebound rules of pleading and damages.

The basis of equity is contained in the maxim “Equity will not suffer an injustice.” Other maxims present reasons for not granting equitable relief. Laches is one such defense.

Laches is based on the legal maxim “Equity aids the vigilant, not those who slumber on their rights.” In other words, “you snooze, you lose.” Laches recognizes that a party to an action can lose evidence, witnesses, and a fair chance to defend himself or herself after the passage of time from the date the wrong was committed. If the defendant can show disadvantages because for a long time he or she relied on the fact that no lawsuit would be started, then the case should be dismissed in the interests of justice.

Laches is based on the legal maxim “Equity aids the vigilant, not those who slumber on their rights.” In other words, “you snooze, you lose.” Laches recognizes that a party to an action can lose evidence, witnesses, and a fair chance to defend himself or herself after the passage of time from the date the wrong was committed. If the defendant can show disadvantages because for a long time he or she relied on the fact that no lawsuit would be started, then the case should be dismissed in the interests of justice.

Ms. Garcia suffered encroachment from a copse of boundary-tree elms for a long time, perhaps too long a time, without doing anything about it. She could have trimmed roots and branches that intruded into her alfalfa fields years before – New Mexico law let her do that – but she fretted and stewed in silence. When she finally wanted to take action, the elms were so big that the trunks themselves had crossed the property line. Her “self-help” would have killed the trees.

The lesson? As the old TV box announcer used to adjure, “You must act now.”

Garcia v. Sanchez, 108 N.M. 388, 772 P.2d 1311 (Ct.App. N.M. 1989). This dispute between neighboring landowners involves trees originally planted on defendant’s property which have overgrown and now encroach upon plaintiff’s property. By the time Garcia bought her land in 1974, ten elm trees planted some years before near the common property line were well established. Although originally planted inside defendant’s property line, over the years the trees had reached full size, and had grown so that nine of them were directly on the boundary, with the trunks encroaching onto plaintiff’s property from one to fourteen inches.

Garcia used her land for growing field crops. Sanchez’s side had a driveway and residence. Garcia didn’t complain about the trees until 8 years after buying her property. Two years after her first complaint, she sued.

The trial court found Garcia’s actions in providing water and nutrients to her crops had caused the trees to grow toward her property, but it concluded that Sanchez negligently maintained the elm trees, allowing the roots and branches to damage the crops on Garcia’s property. The court also found that she has not suffered enough damage to warrant the removal of the trees, and that cutting any substantial portion of the trunks of the trees would seriously harm them. The court found that yearly trenching of the roots and trimming of branches on Garcia’s side of the property line would essentially resolve any problems resulting from the encroachment of tree roots and overhanging branches on her property, so it ordered Sanchez to pay $420.80 for damage to Garcia’s alfalfa, to yearly trench the roots and trim the branches of the trees, and to provide water and nutrients to the trees in order to restrict their growth toward plaintiff’s property.

The parties appealed.

Elms make good boundary trees

Held: The Court of Appeals reversed and remanded. It held that the trees originally planted inside a property line, which had grown to encroach onto adjoining property along boundary, were not jointly owned under the common boundary line test absent an oral or written agreement to have the trees form boundary line between the parties’ property. It agreed that the trial court’s refusal to order that Sanchez remove the encroaching trees was not an abuse of discretion, observing that the trial court had tried to balance equities by weighing the value of trees against the agricultural character of property involved and nature of harm suffered by Garcia.

But the Court of Appeals went further: it ruled that the harm caused to Garcia’s crops by the elms’ overhanging branches and tree roots is not actionable. Instead, following Abbinett v. Fox, the Court held that a plaintiff’s remedies are normally limited to self-help to protect against the encroaching branches and roots. But here, Garcia waited too long: her plan now, after years of suffering in silence, to remove a substantial portion of the root system or trunk of the encroaching trees (the Massachusetts Rule right) may endanger lives or injure Sanchez’s property, and that laches gives a court the right to limit the exercise of her self-help plan under its equitable authority.