LET’S NOT PREJUDGE ANYTHING

My favorite daughter, who holds a Ph.D. in demographics from Cal Berkeley (forgive the proud papa boast), earned her undergraduate degree in linguistics a decade or more ago at an ivy-covered campus some 2,611 miles east of San Francisco Bay.

My favorite daughter, who holds a Ph.D. in demographics from Cal Berkeley (forgive the proud papa boast), earned her undergraduate degree in linguistics a decade or more ago at an ivy-covered campus some 2,611 miles east of San Francisco Bay.

Her B.A. in linguistics (magna cum laude) came after 20 years of listening to her mother and me complain that the English language is going to hell.

You know, to be perfectly honest, at the end of the day, I could literally die at the debasement of the King’s English. A prime example, IMHO, is the ubiquitous airline expression “preboarding.” Since when does one “preboard” by boarding? And the credit card come-on I got the other day, telling me I was “pre-qualified?” Just what is that? Am I qualified? Or not qualified? To me, “qualified” seems rather binary – you are or you aren’t.

But my Ivy League-educated daughter just rolls her eyes and tells me that “language is dynamic.” In other words, 2023 English is not 1923 English, which was not 1823 English, and so on. “Get used to it, Dad,” she counsels me.

This brings me to today’s case. Ann sued her neighbor, Mike, because after she gave him permission to perform “limited trimming” of her Norway maple tree, the branches of which were overhanging his property, she says he over-trimmed, hacked away at the tree roots, and smeared a foreign substance on the root he did not hack. Her expert said the Norway maple was worth $96,000.

C’mon, man. Ninety-six large for a tree considered to be an invasive species? Surely you jest.

Surely she did not. The whole case sounds sketchy. Apparently, Mike performed all of his depredations of the branches and roots from the comfort of his own property. Regular readers of this blog should, at this point, express shock. That sounds like the Massachusetts Rule, especially because Mike argued that her tree had encroached and damaged his property. Why did Mike even require permission to trim overhanging branches and encroaching roots?

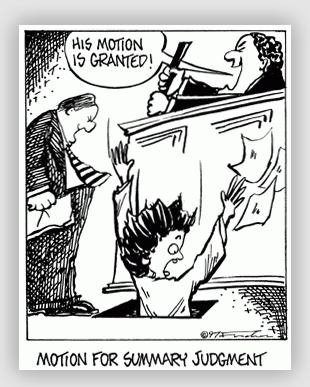

But that’s a question for another day. What the Connecticut trial court was deciding in this opinion was whether Ann was entitled to a prejudgment remedy. “Prejudgment” here is judgment in the same sense that “preboarding” is judgment. If Ann gets her remedy, she gets to attach Mike’s property (bank account, gold bullion, beach house, dogecoins, whatever) up to the amount of the judgment to which she is likely entitled. To do so, she has to show “probable cause” to believe that Mike is liable (that he trespassed, was negligent, whatever) and that she was damaged to a likely amount.

“Prejudgment” sounds a lot like judgment to me, especially because she pleads her claim, he opposes it, and the court decides. Far be it from me to ask how a criminal law concept like “probable cause” found its way into the civil sphere, but the fact that Ann can force a paper trial before the trial, and thereby lock up Mike’s assets (thus restricting his ability to freely use his own property), makes little sense. A canny plaintiff can use the prejudgment remedy route to oppress the defendant and run up litigation costs, thus forcing a settlement that looks a lot like the defendant folding. The fact that the court was able to find probable cause to believe that Mike had trespassed by trimming on his side of the property line suggests that the legal theories are less than perfectly thought out.

It’s one thing to permit a prejudgment remedy where probable cause is present, and there is reason to believe the defendant will run off with his assets in order to make himself judgment-proof. But in Connecticut, you don’t have to show a defendant will cut and run, just that prejudgment, there is probable cause to believe you are likely to get a judgment.

Ann ultimately failed to lock up Mike’s assets because her expert testimony was pretty sloppy. Nevertheless, the whole notion of a prejudgment judgment seems like an erosion of the King’s English, let alone civil procedure.

Greco v. Gallo, 2019 Conn. Super. LEXIS 2963 (Superior Ct. Conn., Nov. 21, 2019). Ann Greco owned a beach house next to a beach house belonging to Michael Gallo. A 40-year-old Norway Maple tree stood on her property near the boundary between the two parcels. Ann claimed that on April 1, 2017, Mike requested permission to prune one of her trees that was overhanging his property. She said she granted limited permission, but Mike pruned well beyond what she had authorized. Ann alleged that Mike damaged the roots of the tree with an ax and that he applied some substance to the tree’s roots, thereby harming and perhaps destroying the tree.

Greco v. Gallo, 2019 Conn. Super. LEXIS 2963 (Superior Ct. Conn., Nov. 21, 2019). Ann Greco owned a beach house next to a beach house belonging to Michael Gallo. A 40-year-old Norway Maple tree stood on her property near the boundary between the two parcels. Ann claimed that on April 1, 2017, Mike requested permission to prune one of her trees that was overhanging his property. She said she granted limited permission, but Mike pruned well beyond what she had authorized. Ann alleged that Mike damaged the roots of the tree with an ax and that he applied some substance to the tree’s roots, thereby harming and perhaps destroying the tree.

Ann sued for compensatory damages, double or treble damages under C.G.S. § 52-560, and punitive damages. Her complaint alleged that Mike was individually liable for her losses under the following legal theories: (1) liability for violation of Connecticut’s tree statute, C.G.S. § 52-560, and (2) liability for common-law negligence.

Ann claimed that Mike performed arboriculture on the tree without a valid license and applied a foreign substance to the tree’s root structure. She further alleges that he or his agents caused the tree to die, and she was harmed through the loss of the tree, its valuable shade, and the cost of the tree’s removal and replacement. She also claimed Mike was negligent, in that he failed to follow her limited pruning instructions and thus breached a duty of responsible conduct and care to her tree when he performed arboriculture without a license. Ann further claimed his negligence caused the death of the tree.

Mike denied everything and argued in addition that § 52-560 does not apply to this case because Mike never entered Ann’s property, and the remaining defendant had no role in the pruning of the tree.

Not to be outdone, Mike counterclaimed against Ann, alleging damages to his real and personal property caused by her negligence for failing to keep her tree from overgrowing and encroaching on his property. He alleges that for a long time before April 2017, Ann’s tree was growing excessively on his property, causing damage to his septic system and roof and requiring demolition and rebuilding of his garage.

Not content with litigating the case to the end, Ann sought to attach some of Mike’s property even before judgment, preventing either from selling it until the case was resolved. Outside of Connecticut, prejudgment attachment normally is intended to ensure that a defendant does not render himself judgment-proof before a case is tried. But in the Nutmeg State, prejudgment attachment does not require a showing that the defendant is likely to hide assets. Instead, it appears to be a civil bludgeon with which a well-heeled plaintiff can beat a defendant into submission by making it impossible for him to do business (or even survive) for as long as a trial goes on.

Held: Ann was not entitled to truss up Mike to the tune of $30,000 pending litigation over one dead tree.

A prejudgment remedy is available upon a finding by the court that “there is probable cause that a judgment in the amount of the prejudgment remedy sought, or in an amount greater than the amount of the prejudgment remedy sought, taking into account any defenses, counterclaims or setoffs, will be rendered in the matter in favor of the plaintiff.” C.G.S. § 52-278d(a)(1). In order to grant prejudgment attachment, a court must determine whether or not there is probable cause to sustain the validity of the applicant’s claim. The plaintiff does not have to establish that she will prevail, only that there is probable cause to sustain the validity of the claim. “The court’s role in such a hearing is to determine probable success by weighing probabilities.

The Court said Ann proposed suing Mike in two counts alleging liability under C.G.S. § 52-560 and liability in common-law negligence.

C.G.S. 52-560 provides that

Any person who cuts, destroys or carries away any trees, timber or shrubbery, standing or lying on the land of another or on public land, except on land subject to the provisions of section 52-560a, without license of the owner, and any person who aids therein, shall pay to the party injured five times the reasonable value of any tree intended for sale or use as a Christmas tree and three times the reasonable value of any other tree, timber or shrubbery; but, when the court is satisfied that the defendant was guilty through mistake and believed that the tree, timber or shrubbery was growing on this land, or on the land of the person for whom he cut the tree, timber or shrubbery, it shall render judgment for no more than its reasonable value.

Section 52-560 embodies the long-standing common law that predated its passage and includes the legal concepts of trespass and damages. The elements of an action for trespass are (1) ownership or possessory interest in land by the plaintiff; (2) invasion, intrusion, or entry by the defendant affecting the plaintiff’s exclusive possessory interest; (3) done intentionally; and (4) causing direct injury.” A trespass can exist without personal entry onto the land of another. Anything a person does that appropriates adjoining land or substantially deprives an adjoining owner of the reasonable enjoyment of his or her property is an unlawful use of one’s property.

Section 52-560 does not give a new and independent cause of action, the Court said, but instead prescribes the measure of damages in cases where compensatory damages would, in the absence of the statute, be recoverable.” An action under § 52-560, therefore, is an action in trespass with a specifically prescribed measure of recovery of damages. As with trespass, the plaintiff cannot recover if the defendant had the “license,” or permission of, among others, the owner. Failure to prove the elements of the underlying trespass, the Court held, dooms an action under § 52-560.

Here, the Court held, Ann claims the evidence supports liability against Mike for violating C.G.S. 52-560, in that he admittedly pruned the tree, used an ax or hatchet on the roots of the tree, and placed some substance around the root region of the tree so as to harm it permanently. Although Mike’s actions all occurred from his neighboring property, Ann claims the trespass is established through his unauthorized actions on the tree from his property. Mike’s testimony supports that he did do such pruning from his property on her tree, but Ann alleges he went too far and was much too aggressive in that pruning process. And even further, the evidence showed he never asked permission to take an ax to the tree roots on his property, nor to put any foreign substances at or near the tree roots. This conduct beyond the permission given by Ann, the Court said, supported the probable cause finding on the trespass issue.

Here, the Court held, Ann claims the evidence supports liability against Mike for violating C.G.S. 52-560, in that he admittedly pruned the tree, used an ax or hatchet on the roots of the tree, and placed some substance around the root region of the tree so as to harm it permanently. Although Mike’s actions all occurred from his neighboring property, Ann claims the trespass is established through his unauthorized actions on the tree from his property. Mike’s testimony supports that he did do such pruning from his property on her tree, but Ann alleges he went too far and was much too aggressive in that pruning process. And even further, the evidence showed he never asked permission to take an ax to the tree roots on his property, nor to put any foreign substances at or near the tree roots. This conduct beyond the permission given by Ann, the Court said, supported the probable cause finding on the trespass issue.

Ann also claimed, in addition to the § 52-560 count, that Mike was negligent. Such a common-law cause of action is permitted in tree damage cases, in addition to the statutory count. The essential elements of a cause of action in negligence are duty, breach of that duty, causation, and actual injury. Here, the Court said, the evidence permitted the court to find that Mike owed a duty to Ann once he asked her for permission to prune the tree, to exercise that permission reasonably and within the scope of permission she gave him.

The testimony and the photographs offered at the hearing supported the claim that Mike may not have been reasonable in how he conducted himself after Ann gave him limited permission to prune. Taking an ax or hatchet to the roots and placing foreign substances at the root areas, the Court held, may be a sufficient basis to find that he breached that duty and sustain the validity of Ann’s negligence claim. Thus, there is probable cause to sustain the validity of the negligence claim against Mike.

However, before the court could grant Ann’s application for prejudgment attachment, the court had to also find that the damages she claimed were supported by the requisite probable cause.

Section 52-560 is very clear as to what is or is not the measure of damages in tree damage cases, the Court ruled. Ann could seek damages for the trespass itself, for the value of the trees removed, considered separately from the land, or for the recovery of damages to the land resulting from the special value of the trees as shade or ornamental trees while standing on the land. For a mere unlawful entry upon land, nominal damages only would be awarded. If the purpose of the action is only to recover the value of the trees as chattels, after severance from the soil, the rule of damages is the market value of the trees for timber or fuel.

Section 52-560 is very clear as to what is or is not the measure of damages in tree damage cases, the Court ruled. Ann could seek damages for the trespass itself, for the value of the trees removed, considered separately from the land, or for the recovery of damages to the land resulting from the special value of the trees as shade or ornamental trees while standing on the land. For a mere unlawful entry upon land, nominal damages only would be awarded. If the purpose of the action is only to recover the value of the trees as chattels, after severance from the soil, the rule of damages is the market value of the trees for timber or fuel.

For the injury resulting to the land from the destruction of trees which, as a part of the land, have a peculiar value as shade or ornamental trees, a different rule of damages obtains, namely, the reduction in the pecuniary value of the land occasioned by the act complained of.

The proper measure of damages is either “the market value of the tree, once it is severed from the soil, or the diminution in the market value of the… real property caused by the cutting.”

Ann overreached. She sought an attachment of $30,000 each over the real and personal property of all three defendants and was “rather unclear as to the exact basis for the alleged damages related to the Norway Maple in question. And, there is contradictory evidence provided by each alleged expert arboriculturist on this topic.”

Expert testimony from Ann’s and Mike’s experts set the “reasonable value” of the tree at $98,000. The Court noted drily that

it is unclear if these sums are replacement cost figures for said tree or if they are values of the tree as timber once cut. Neither expert offered opinions with any reasonable degree of arboricultural probability in their written reports nor in their testimony at trial, and neither expert provided sufficient scientific methodology or reasoning for how they each arrived at the dollar amounts testified to. In fact, both witnesses had never testified in court before, and both had limited prior experience in placing a valuation on trees in question, such as the case at bar. Their testimony did not provide clear evidence on the replacement cost of the tree versus the cost of the tree once cut for potential lumber, as required by the statute and case law for the measure of damages under §52-560.

The Court noted that “trial judges are afforded wide discretion to serve as gatekeepers for scientific evidence because a relevance standard of admissibility inherently involves an assessment of the validity of the proffered evidence. More specifically, if scientific evidence has no grounding in scientific fact but instead is based on conjecture and speculation, it cannot in any meaningful way be relevant to resolving a disputed issue.”

The Court noted that “trial judges are afforded wide discretion to serve as gatekeepers for scientific evidence because a relevance standard of admissibility inherently involves an assessment of the validity of the proffered evidence. More specifically, if scientific evidence has no grounding in scientific fact but instead is based on conjecture and speculation, it cannot in any meaningful way be relevant to resolving a disputed issue.”

Therefore, while the Court found probable cause for believing Mike would be liable, it could not find sufficient probable cause as to the amount of damages Ann claimed to justify the placement of a monetary attachment on Mike’s property.

– Tom Root