WHAT DID THE GOVERNMENT KNOW, AND WHEN DID IT KNOW IT?

One of the enduring lines from the endless (or so it seemed at the time) Watergate investigation was Howard Baker’s famous question, “What did the president know and when did he know it?” On the answer to that question turned the culpability of the President for the high crimes and misdemeanors of his minions. It still does, despite the fact that we now know that the Watergate investigation timetable was a rocket ship compared to Whitewater-Lewinsky, Valerie Plame, Benghazi–Fast and Furious–IRS, January 6th, E. Jean Carroll, Stormy Daniels, and (now) Joe Biden’s health.

It’s a great question. Many plaintiffs have discovered that possessing or lacking the answer to it often is the difference between winning and losing a tort action.

We talked about strict liability yesterday, but that’s not generally the way we do things. Were it otherwise, commerce and society would screech to a halt, because any act — regardless of how responsibly it was performed — could lead to liability and financial ruin.

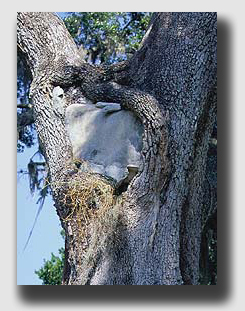

Consider today’s case. A tree branch cracked and settled so far down the tree that it dangled dangerously low over a road. Linda hit it, damaging her car. No one would disagree that the branch should not have been there. Nevertheless, the harm it caused did not mean Linda could pick the State of Ohio’s pocket for repairs itself unless the State had a duty to the motoring public which it failed to discharge.

Shouldn’t the Ohio Department of Transportation have known about the danger? Should it not have corrected the defect before Linda happened along? Shouldn’t those highway workers do something to justify their paychecks? That all depends on the State’s knowledge of the defect. Or, as the late Sen. Howard Baker might have put it, “What did ODOT know, and when did it know it?”

Coleman v. Ohio DOT, 2009-Ohio-6887 (Ct. Claims, Aug, 25, 2009), 2009 Ohio Misc. LEXIS 3. One February day, Linda Coleman was driving along a state highway a half mile outside of the village of Westville, Ohio, when her 2004 Honda Accord hit a very low tree branch overhanging the road. The impact broke the windshield and damaged the right side of her car.

Linda sued ODOT, theorizing that the damage to her car was proximately caused by ODOT’s negligence in failing to maintain the roadway free of hazardous conditions. She sought a paltry $745.01, the cost of fixing her Honda.

Linda sued ODOT, theorizing that the damage to her car was proximately caused by ODOT’s negligence in failing to maintain the roadway free of hazardous conditions. She sought a paltry $745.01, the cost of fixing her Honda.

ODOT denied liability, contending that none of its employees or agents had any knowledge of the hazardous overhanging tree limb prior to Linda’s collision with it. ODOT denied receiving any reports about the limb prior to the accident from anyone. ODOT did receive a report after Linda struck the tree, and responded by dispatching two ODOT workers to remove the tree limb the same day Linda hit it. ODOT argued that the facts suggested that “it is likely the tree limb existed for only a short time before the incident.”

ODOT related that its manager for that county inspected all state roadways n the county at least twice a month. Apparently, no overhanging tree condition was discovered at Milepost 2.50 on State Route 560 the last time that section of the roadway was inspected.

Held: ODOT had no liability to Linda.

To be sure, ODOT has the duty to maintain its highways in a reasonably safe condition for the motoring public. However, the state agency is not an insurer of the safety of its highways. In order to prove a breach of ODOT’s duty to maintain the highways, Linda would have had to prove that ODOT had actual or constructive notice of the precise condition or defect alleged to have caused the accident. ODOT would only be liable for a roadway condition of which it had notice but failed to take reasonable steps to correct.

In order to recover on a claim of this type, the Court said, Linda had to show either that ODOT had actual or constructive notice of the low-hanging tree limb and failed to respond in a reasonable time or responded in a negligent manner, or that ODOT in a general sense maintains its highways negligently. For constructive notice to be proven, Linda would have had to show that sufficient time had passed after the dangerous nature of the tree limb came into being so that, under the circumstances, ODOT should have learned of its existence.

In order to recover on a claim of this type, the Court said, Linda had to show either that ODOT had actual or constructive notice of the low-hanging tree limb and failed to respond in a reasonable time or responded in a negligent manner, or that ODOT in a general sense maintains its highways negligently. For constructive notice to be proven, Linda would have had to show that sufficient time had passed after the dangerous nature of the tree limb came into being so that, under the circumstances, ODOT should have learned of its existence.

The court hearing the case may not infer that ODOT knew, unless Linda presented evidence of when the defective limb first appeared to be too low over the roadway. Here, Linda had no proof that ODOT had any notice, either actual or constructive, of the damage-causing tree limb.

Generally, to prove negligence, a plaintiff must prove that a defendant owed her a duty, that it breached that duty, and that the breach proximately caused her injuries. She must also show she suffered a loss, and that this loss was proximately caused by the defendant’s negligence.

Linda had no evidence that her injury was proximately caused by ODOT’s negligence because she could not show when the dangerous condition came into being. Therefore, she was unable to show that the damage-causing object was connected to any conduct under ODOT’s control, or to any ODOT negligence.

– Tom Root