RIGHT THING, WRONG REASON

The right things usually get done for the wrong reasons. The Internet, which knows all (or soon will) attributes the aphorism to James Carville, but I remember the exact line being penned by Washington columnist Drew Pearson in a political potboiler of his, The President, which I read as a lad in the summer of 1971.

The right things usually get done for the wrong reasons. The Internet, which knows all (or soon will) attributes the aphorism to James Carville, but I remember the exact line being penned by Washington columnist Drew Pearson in a political potboiler of his, The President, which I read as a lad in the summer of 1971.

Sorry, James, When it comes to credit for this particular witticism, you didn’t build that.

Today’s case is a reminder to all the states that claim the Massachusetts Rule, the Hawaii Rule, the Virginia Rule and so on that there is nothing new under the sun. Well before those rules came into being, the Washington State Supreme Court grappled with the encroachment issue and reluctantly decided an early version of the Hawaii Rule: where there is encroachment that causes “sensible harm,” the adjoining landowner may either trim back the offending growth or sue to force the tree’s owner to do it.

Ironically, settling the law (the right thing to do) probably got done for the wrong reason (bad blood between neighbors). We have seen how the Massachusetts Rule began in Michigan. Now, it seems the Hawaii Rule may have started in Washington. Sorry, Hawaii, you didn’t build that.

Truly, there’s nothing new under the sun.

Gostina v. Ryland, 116 Wash. 228, 199 P. 298 (Supreme Ct. Wash. 1921). A.L. Ryland had owned his place for many years when new neighbors, the Gostinas, moved in next door. A.L. had a Lombardy poplar tree growing about two feet from the Gostina property and a fir tree in the rear of the property, also about two feet from the division fence. On top of that, A.L. maintained a creeping vine, growing in a rustic box on top of a large stump, a few feet from the division fence, and some raspberry bushes and a rosebush growing near the property line.

About a year after they moved in, the Gostinas had their lawyer write to A.L. to tell him the branches of his fir tree were overhanging the Gostina property and dropping needles and that A.L.’s ivy was running under the fence and onto the Gostinas’ lawn. The lawyer demanded that A.L. cut off the fir tree branches at the point where they crossed the boundary line, remove the ivy from the Gostinas’ property, and keep the tree and ivy from encroaching ever again.

About a year after they moved in, the Gostinas had their lawyer write to A.L. to tell him the branches of his fir tree were overhanging the Gostina property and dropping needles and that A.L.’s ivy was running under the fence and onto the Gostinas’ lawn. The lawyer demanded that A.L. cut off the fir tree branches at the point where they crossed the boundary line, remove the ivy from the Gostinas’ property, and keep the tree and ivy from encroaching ever again.

A.L. was unimpressed, so the Gostinas brought a suit for abatement of a nuisance. (And we thought frivolous litigation was a recent phenomenon!) A.L. argued that the lawsuit was merely for spite and vexation, and that the Gostinas knew the tree and ivy were there when they moved in. Only after a neighborly disagreement, A.L. claimed, did the Gostinas sue.

The trial court did not care about such nonsense, holding that where branches of trees overlap adjoining property, the owner of the adjoining property has an absolute legal right to have the overhanging branches removed by a suit of this character.

The Gostinas appealed.

Held: A.L.’s tree and ivy were a nuisance, and the Gostinas’ claimed damages, although ridiculously minor, were enough to permit them to maintain a nuisance action against A.L. Ryland.

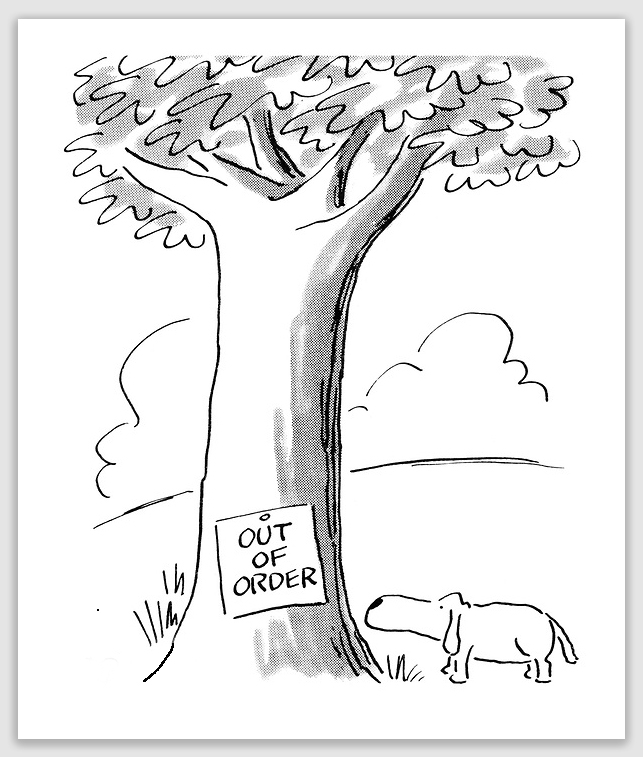

The Court agreed that under Washington law, trees and plants growing into the yard of another constituted a nuisance, “to the extent to which the branches overhang the adjoining land. To that extent they are technical nuisances, and the person over whose land they extend may cut them off, or have his action for damages, if any have been sustained therefrom, and an abatement of the nuisance against the owner or occupant of the land on which they grow; but he may not cut down the tree, neither can he cut the branches thereof beyond the extent to which they overhang his soil.”

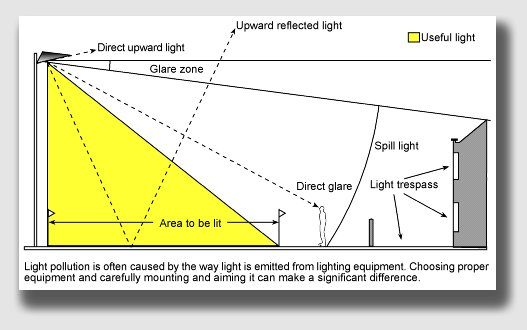

From ancient times, the Court said, it has been a principle of law that the landowner has the exclusive right to the space above the surface of his or her property: “To whomsoever the soil belongs, he also owns to the sky and to the depths. The owner of a piece of land owns everything above it and below it to an indefinite extent.” On the same principle, the Court held that the branches of trees extending over adjoining land constitute a nuisance, at least in the sense that the owner of the land encroached upon may himself cut off the offending growth.

A property owner may not “maintain an action against another for the intrusion of roots or branches of a tree which is not poisonous or noxious in its nature. His remedy in such cases is to clip or lop off the branches or cut the roots at the line.” What it came down to, the Court held, was that “the powerful aid of a court of equity by injunction can be successfully invoked only in a strong and mischievous case of pressing necessity” and there must be “satisfactory proof of real substantial damage.”

Here, the Court said, what the Gostinas complained of was “so insignificant that respondents did not even claim them or prove any amount in damages–but simply proved that the leaves falling from the overhanging branches of the poplar tree caused them some additional work in caring for their lawn; and that the needles from the overhanging branches of the fir tree caused them some additional work in keeping their premises neat and clean, and fell upon their roof and caused some stoppage of gutters; and that sometimes, when the wind blew in the right directions, the needles blew into the house and annoyed the occupants. We cannot avoid holding, therefore, that these are actual, sensible damages, and not merely nominal, and, although insignificant, the insignificance of the injury goes to the extent of recovery, and not to the right of action.”

Here, the Court said, what the Gostinas complained of was “so insignificant that respondents did not even claim them or prove any amount in damages–but simply proved that the leaves falling from the overhanging branches of the poplar tree caused them some additional work in caring for their lawn; and that the needles from the overhanging branches of the fir tree caused them some additional work in keeping their premises neat and clean, and fell upon their roof and caused some stoppage of gutters; and that sometimes, when the wind blew in the right directions, the needles blew into the house and annoyed the occupants. We cannot avoid holding, therefore, that these are actual, sensible damages, and not merely nominal, and, although insignificant, the insignificance of the injury goes to the extent of recovery, and not to the right of action.”

Since the Gostinas had the statutory right to bring an action for abatement of a nuisance and had shown some “actual and sensible damages, although insignificant,” they are entitled to go forward with the suit. “The remainder of the trees will doubtless shed their leaves and needles upon the respondents’ premises,” the Court prophesied, “but this they must endure positively without remedy.”

The Court was not really that fooled: this was a spite suit, but that alone was not disqualifying. While the Gostinas’ action against A.L. “has some appearance of being merely a vexatious suit,” the Court said, A.L. did “admit that the tree boughs do overhang respondent’s lot to some extent. There is sufficient foundation in fact to sustain a case…”

– Tom Root