STAYIN’ ALIVE

Last Friday, pro se plaintiff Caryn Rickel survived the arguments advanced by the slick lawyers representing her bamboo-lovin’ neighbors, the Komaromis. The trial court held that her complaint about the Komaromis’ invading bamboo was a claim on which she could get relief.

Last Friday, pro se plaintiff Caryn Rickel survived the arguments advanced by the slick lawyers representing her bamboo-lovin’ neighbors, the Komaromis. The trial court held that her complaint about the Komaromis’ invading bamboo was a claim on which she could get relief.

But subsequently, the trial court bought the Komaromis’ argument that because Caryn admitted that they planted the bamboo in 1997 and Caryn sustained damage in 2005, she had at most until 2008 to sue for trespass and nuisance.

The reason, of course, is the statute setting limitations, that is, deadlines by which certain legal complaints have to be brought. The Komaromis’ lawyer probably shouted “a-ha!” when he found that Caryn had admitted she was damaged five years before she sued. Certainly, the trial court shouted it when it agreed with the Komaromis and dismissed Caryn’s lawsuit as untimely.

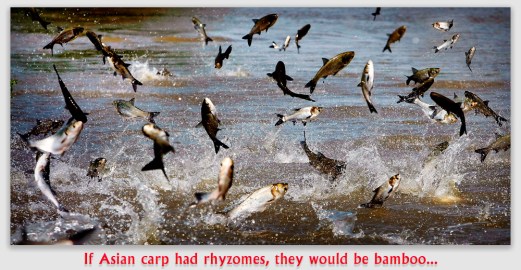

But for a novice, Caryn was pretty sharp. She took an appeal, arguing that every day the kudzu-like bamboo grew was a whole new affront to her property, and thus the trespass was continuing. The appeals court agreed, although not without a lot of confusing differentiation between continuing trespasses and continuing nuisances, on the one hand, and permanent trespasses and permanent nuisances on the other.

I’m not sure I see the distinction myself. It may be that the confusing definitions won’t help, leaving it like obscenity: we can’t describe it, but we know it when we see it.

I’m not sure I see the distinction myself. It may be that the confusing definitions won’t help, leaving it like obscenity: we can’t describe it, but we know it when we see it.

For now, Caryn survives a second near-dismissal experience, and she stays alive to fight the bamboo fight.

Rickel v. Komaromi, 144 Conn. App. 775, 73 A.3d 851 (Ct.App. Conn. 2013). After plaintiff Caryn Rickel won the right to go forward on her claim that the Komaromis’ bamboo had invaded her property, the Komaromis won summary judgment against her in the trial court. Caryn claimed nuisance and trespass. The trial court ruled that because the bamboo began its inexorable crawl across Caryn’s backyard in 2005, her suit filed in 2010 was well beyond the three-year statute of limitations for such actions.

Caryn appealed, arguing that the repeated bamboo encroachment from the Komaromis’ property to her property constituted a continuing nuisance and a continuing trespass, and thus the statute of limitations did not start running.

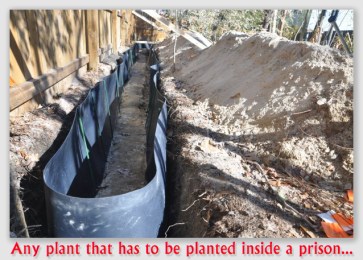

The Komaromis lived next to Caryn Rickel. In July 1997, the Komaromis planted phyllostachys aureosulcata, a type of invasive running bamboo, along their corner property line, but they did not put up any barrier to contain it. The bamboo encroached upon Caryn’s property. In 2005, during the installation of a patio at the corner of Caryn’s property, a landscaper used a backhoe and dump truck in order to eradicate the bamboo, and then installed steel sheathing along this corner property line in order to protect the patio. Despite the steel sheathing, the bamboo had reentered the area by July 2010.

Caryn sued the Komaromis four months later, bringing claims of nuisance, trespass and negligence. She alleged in her complaint that the bamboo “further and repeatedly encroached” on her property and continued to do so. The Komaromis raised a statute of limitations defense on all of the claims against them.

Caryn sued the Komaromis four months later, bringing claims of nuisance, trespass and negligence. She alleged in her complaint that the bamboo “further and repeatedly encroached” on her property and continued to do so. The Komaromis raised a statute of limitations defense on all of the claims against them.

The trial court granted the Komaromis’ motion, concluding that the applicable statutes of limitations had provided Caryn with a maximum of three years from “the date of the act or omission complained of” to bring suit. Because there was no dispute that the Komaromis planted the bamboo in 1997 or that Caryn “discovered the actionable harm in 2005…” Because Caryn did not commence her action against the Komaromis until 2010, the court held that each count of the action was time-barred as a matter of law.

On appeal, Caryn claimed that the trial court failed to address the factual question of whether a nuisance or trespass is continuing or permanent requires the denial of a summary judgment motion made solely on statute of limitations grounds. She claims that this is because, for statute of limitations purposes, each instance of nuisance or trespass in a continuing nuisance or trespass creates a new cause of action, while a permanent nuisance or trespass involves a discrete occurrence of nuisance or trespass from which the applicable statute of limitations begins to run.

Held: The Komaromis’ bamboo was engaged in a continuing trespass, and thus Caryn’s lawsuit was timely.

Caryn’s complaint alleged that the Komaromis’ bamboo repeatedly has encroached on her property, resulting in a continuing nuisance and a continuing trespass. For example, in her nuisance count, she alleged the Komaromis “have planted this nonnative invasive bamboo with no containment of any kind. They have continued to cultivate it and freely allow it to aggressively spread to… adjacent properties… This has been continual nuisance to my use and enjoyment of my land.”

Similarly, Caryn complained the Komaromis “have allowed this nonnative invasive bamboo to aggressively spread from their original planting which was directly on my property line to all three of the [neighboring] properties. The infestation is massive… and has continuously been aggressively invading my land.” Caryn’s continuing nuisance and trespass allegations, the Court said, therefore factor into the question of whether the court correctly concluded that the defendants met their summary judgment burden with respect to the plaintiff’s nuisance and trespass claims, as framed by her complaint.

The Court noted that recent cases treat trespass as involving acts that interfere with a plaintiff’s exclusive possession of real property and nuisance cases as involving acts interfering with a plaintiff’s use and enjoyment of real property. The essentials of an action for trespass are (1) ownership or possessory interest in land by the plaintiff; (2) invasion, intrusion or entry by the defendant affecting the plaintiff’s exclusive possessory interest; (3) done intentionally; and (4) causing direct injury…” Because it is the right of the owner to exclusive possession that is protected by an action for trespass, usually the intrusion of the property must be physical. Thus, the Court said, in order to be liable for trespass, one must intentionally cause some substance or thing to enter upon another’s land.”

The statute of limitations for trespass actions in Connecticut is General Statutes § 52-577, which provides: “No action founded upon a tort shall be brought but within three years from the date of the act or omission complained of.” The only facts material to the trial court’s decision on a motion for summary judgment must be the date of the wrongful conduct alleged in the complaint and the date the action was filed.

A “private nuisance,” on the other hand, “is a nontrespassory invasion of another’s interest in the private use and enjoyment of land… The law of private nuisance springs from the general principle that it is the duty of every person to make reasonable use of his own property so as to occasion no unnecessary damage or annoyance to his neighbor… In order to recover damages in a common-law private nuisance cause of action, a plaintiff must show that the defendant’s conduct was the proximate cause of an unreasonable interference with the plaintiff’s use and enjoyment of his or her property. The interference may be either intentional… or the result of the defendant’s negligence.” A permanent nuisance is one that inflicts a permanent injury upon real estate, while a temporary nuisance is one where there is but temporary interference with the use and enjoyment of property. Whether a nuisance is temporary or permanent is ordinarily a question of fact.”

The statute of limitations for a nuisance claim based on alleged negligent conduct is General Statutes § 52-584: “No action to recover damages for injury to real property, caused by negligence, or by reckless or wanton misconduct shall be brought but within two years from the date when the injury is first sustained or discovered or in the exercise of reasonable care should have been discovered, and except that no such action may be brought more than three years from the date of the act or omission complained of…” An injury occurs when a party suffers some form of actionable harm.

The statute of limitations for a nuisance claim based on alleged negligent conduct is General Statutes § 52-584: “No action to recover damages for injury to real property, caused by negligence, or by reckless or wanton misconduct shall be brought but within two years from the date when the injury is first sustained or discovered or in the exercise of reasonable care should have been discovered, and except that no such action may be brought more than three years from the date of the act or omission complained of…” An injury occurs when a party suffers some form of actionable harm.

Nuisance and negligence may share the same statute of limitations, depending on the factual basis for the nuisance claim, but otherwise, they are completely distinct torts, different in their nature and in their consequences. A claim for nuisance is more than a claim of negligence, and negligent acts do not, in themselves, constitute a nuisance; rather, negligence is merely one type of conduct upon which liability for nuisance may be based. “Nuisance,” the Court said, “is a word often very loosely used; it has been not inaptly described as a catch-all of ill-defined rights. There is perhaps no more impenetrable jungle in the entire law than that which surrounds the word nuisance… There is general agreement that it is incapable of any exact or comprehensive definition.”

In applying these principles to the plaintiff’s claims, the Court said, “summary judgment may be granted where the claim is barred by the statute of limitations… as long as there are no material facts concerning the statute of limitations in dispute.” But here, the date of the act or omission and the date when Caryn first sustained or discovered injury depend on whether the alleged nuisance and trespass are continuing or permanent. Caryn argued that this is because, for statute of limitations purposes, each instance of nuisance or trespass in a continuing nuisance or trespass situation creates a new cause of action, whereas a permanent nuisance or trespass situation involves a discrete occurrence of nuisance or trespass from which the applicable statute of limitations begins to run.

The applicable statute of limitations runs differently for a continuing nuisance or trespass than it does for a permanent nuisance or trespass. For limitations purposes, the Court ruled, a permanent nuisance claim accrues when the injury first occurs or is discovered while a temporary nuisance claim accrues anew upon each injury. Therefore, in the case of a continuing trespass, the statute of limitations does not begin to run from the date of the original wrong but rather gives rise to successive causes of action each time there is an interference with a person’s property. If there are multiple acts of trespass, then there are multiple causes of action, and the statute of limitations begins to run anew with each act.

On the other hand, the Court said, if a trespass is characterized as permanent, the statute of limitations begins to run from the time the trespass is created, and the trespass may not be challenged once the limitation period has run.” Whether a nuisance is deemed to be continuing or permanent in nature determines the manner in which the statute of limitations will be applied. If a nuisance is not able to be abated, it is permanent, and a plaintiff is allowed only one cause of action to recover damages for past and future harm. A nuisance is deemed not abatable, even if possible to abate, if it is one whose character is such that, from its nature and under the circumstances of its existence, it will probably continue indefinitely.

A nuisance is not considered permanent if it is one that can and should be abated. In this situation, every continuance of the nuisance is a fresh nuisance for which a fresh action will lie, and the statute of limitation will begin to run at the time of each continuance of the harm.

Similarly, with trespass, the typical trespass is complete when it is committed; the cause of action accrues, and the statute of limitations begins to run at that time. However, when the defendant erects a structure or places something on or underneath a plaintiff’s land, the invasion continues if the defendant fails to remove the harmful condition. In such a case, there is a continuing tort so long as the offending object remains and continues to cause the plaintiff harm. Each day a trespass of this type continues, a new cause of action arises.”

Here, Caryn alleged facts to support her claims that the Komaromis’ conduct in planting the bamboo and then failing to control its growth resulted in a continuing nuisance and a continuing trespass. In seeking summary judgment, however, the Komaromis referred only to three dates to establish the untimeliness of Caryn’s claims — the 1997 planting of the bamboo, the 2005 installation of the patio, and the 2010 commencement of the action – ignoring Caryn’s other allegations.

Here, Caryn alleged facts to support her claims that the Komaromis’ conduct in planting the bamboo and then failing to control its growth resulted in a continuing nuisance and a continuing trespass. In seeking summary judgment, however, the Komaromis referred only to three dates to establish the untimeliness of Caryn’s claims — the 1997 planting of the bamboo, the 2005 installation of the patio, and the 2010 commencement of the action – ignoring Caryn’s other allegations.

By conducting its summary judgment analysis only on the basis of the 1997, 2005 and 2010 dates, the trial court did not address the allegations of the Komaromis’ failure to control the underground spread of the bamboo rhizomes and the above-ground spread of the bamboo on Caryn’s property. This continuing underground and above-ground activity on Caryn’s property created a genuine issue of material fact about whether the statutes of limitations were a bar to all of her claims encompassed in her trespass and nuisance counts.

Whether the alleged nuisance and trespass by the rhizomes and bamboo were continuing or permanent presents a genuine issue of material fact with respect to the plaintiff’s trespass and nuisance counts. The trial court erred in rendering summary judgment without addressing the plaintiff’s continuing nuisance and continuing trespass allegations, because, by doing so, the court overlooked genuine issues of material fact about whether the alleged nuisance and trespass were continuing or permanent, and thus whether the applicable statutes of limitations had run on the plaintiff’s nuisance and trespass claims.

– Tom Root

I regret to say that I was all tied up with important activities, and thus I was unable to post anything of substance today.

I regret to say that I was all tied up with important activities, and thus I was unable to post anything of substance today.  The dinosaur ate a plastic taco before the party broke up.

The dinosaur ate a plastic taco before the party broke up.