A PRÉCIS ON ENCROACHMENT

North Dakota – you used to be able to see the gas flares from outer space. Now, the place is hot once again.

It’s been a roller coaster for North Dakota over the past decade. Early on, North Dakota was a pretty happenin’ place. It was the No. 2 oil producer in the country, unemployment there was at a measly 2.6%, 18,000 more people moved there in 2013 than left… and the state had so much underground methane that it was flaring $100 million in natural gas a month that it couldn’t use.

Suddenly, you couldn’t give away houses there, equipment firms were saddled with bulldozers they couldn’t use, and boom towns were going bust.

But what goes around comes back again. By 2018, Nodak was back on top, pumping as much oil as all of Venezuela (although that’s a pretty low bar). The pandemic drove a green stake through the heart of oil, but in 2020, business heated up again. As of the end of 2024, Nodak was “mature” but still pumping 1.2 million barrels a day, a third more than Maduro’s workers’ paradise.

But I’m not here to talk fracking. The natural resources we care about around here are underground only to the extent of their root systems – root systems that, along with branches, can occasionally encroach on the neighbors. And that can be a real pain in the neck.

Over a decade ago, our guest justices from the North Dakota Supreme Court took time from deciding mineral rights, liability for train derailments, mobile home park regulation and the like to consider the law of tree encroachment. They did a bang-up job of summarizing the history, policy bases and goals of the various rules, before thoughtfully consigning the Massachusetts Rule’s proscription against lawsuits to what we here at treeandneighborlawblog call the “wood chipper of history.”

Back to the pain-in-the-neck tree. Dr. Richard Herring knows something about pains in the neck. They’re his livelihood, as long as they’re found in his patients. But this chiropractor had to deal with another pain in the neck, too. The property next door, on which sat an apartment building, had a large tree with branches that were overhanging Dr. Herring’s bone-crunching office. He fought back with self-help, trimming branches, cleaning up the debris that clogged his gutters, and raking up the mess the tree made every fall. But he couldn’t keep ahead. Finally, the branches damaged his building, and the debris created an ice dam on his roof that flooded the place.

The absentee owners and hired managers at the apartment house next refused his entreaties to care for the tree. So he sued, claiming that they had a duty to manage the tree in such a way that it didn’t mess up his place. The trial court threw the suit out, telling the good doctor that he could trim the parts of the tree that were overhanging his place, but that was his only remedy.

The absentee owners and hired managers at the apartment house next refused his entreaties to care for the tree. So he sued, claiming that they had a duty to manage the tree in such a way that it didn’t mess up his place. The trial court threw the suit out, telling the good doctor that he could trim the parts of the tree that were overhanging his place, but that was his only remedy.

“Wait,” you say, “that’s the Massachusetts Rule.” Right you are. But, as the North Dakota Supreme Court decided, there are other rules out there as well, including some that it thinks are a whole lot better than the doddering relic from Michalson v. Nutting. It reversed the trial court, holding that a tree owner does indeed have a duty to care for his or her trees so as to avoid damage to others.

In its thoughtful opinion, the Court wrote perhaps as fine a roundup on tree encroachment rules as has yet been written.

Herring v. Lisbon Partners Credit Fund, Ltd., 2012 N.D. 226, 823 N.W.2d 493 (Supreme Ct. N.D., 2012). Dr. Herring owned a commercial building in Lisbon housing his chiropractic practice. The apartment building next door is owned by Lisbon Partners and managed by Five Star. Branches from a large tree located on Lisbon Partners’ property overhang Herring’s property and brush against his building. For many years, Dr. Herring trimmed back the branches and cleaned out the leaves, twigs, and debris that would fall from the branches and clog his downspouts and gutters. He claimed that the encroaching branches caused water and ice dams to build up on his roof, and eventually caused water damage to the roof, walls, and fascia of his building. Herring contends that, after he had the damages repaired, he requested compensation from Lisbon Partners and Five Star, but they denied responsibility for the damages.

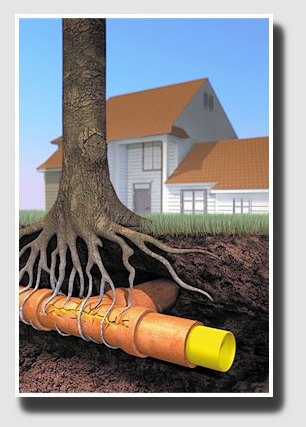

Encroaching tree roots and branches can sometimes be unsightly

Dr. Herring sued Lisbon Partners and Five Star for the cost of repairing his building, claiming the companies had committed civil trespass and negligence, and maintained a nuisance by breaching their duty to maintain and trim the tree so that it did not cause damage to his property. The district court granted Lisbon Partners and Five Star’s motion for summary judgment, dismissing Herring’s claims. The court held Lisbon Partners and Five Star had no duty to trim or maintain the tree, and Herring’s remedy was limited to self-help. He could trim the branches back to the property line at his own expense, but that was it.

Held: The trial court’s dismissal was reversed, and Dr. Herring was given his day in court.

The North Dakota Supreme Court began its analysis by observing that the Massachusetts Rule was the original common law on tree law in the United States, holding that a landowner has no liability to neighboring landowners for damages caused by encroachment of branches or roots from his trees, and the neighboring landowner’s sole remedy is self-help: the injured neighbor may cut the intruding branches or roots back to the property line at his or her own expense. The basis for the Massachusetts Rule is that it is “wiser to leave the individual to protect himself, if harm results to him from the exercise of another’s right to use his own property in a reasonable way, than to subject that other to the annoyance and burden of lawsuits, which would likely be both countless and, in many instances, purely vexatious.

The Hawaii Rule, on the other hand, rejected the Massachusetts approach as overly simplistic. Instead, it held that the owner of a tree may be liable when encroaching branches or roots cause harm, or create imminent danger of causing harm, beyond merely casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers, or fruit. When overhanging branches or protruding roots actually cause, or there is imminent danger of them causing, sensible harm to property other than plant life, in ways other than by casting shade or dropping leaves, flowers, or fruit, the damaged or imminently endangered neighbor may require the owner of the tree to pay for the damages and to cut back the endangering branches or roots and, if such is not done within a reasonable time, the damaged or imminently endangered neighbor may cause the cutback to be done at the tree owner’s expense.

The Restatement Rule, based upon the Restatement (Second) of Torts §§ 839-840 (1979), distinguishes between natural and artificial conditions on the land. Under the Restatement Rule, if the tree was planted or artificially maintained it may be considered a nuisance and its owner may be liable for resulting damages, but there is no liability for a naturally growing tree that encroaches upon neighboring property.

The Virginia Rule, adopted in 1939, makes a distinction between noxious and non-noxious trees. Under the old Virginia rule, a tree encroaching upon neighboring property will be considered a nuisance, and an action for damages can be brought if it is a “noxious” tree and has inflicted a “sensible injury.”

The district court concluded that under N.D.C.C. § 47-01-12, Herring had a “right” to do as he wished with the overhanging branches and underlying roots of the tree, and therefore this portion of the tree was “just as much the responsibility of the adjacent landowner as it is the owner of the trunk.” In effect, the district court concluded that because Herring had the “right” to the branches above his property, he, therefore, had the responsibility to maintain them as well.

The state Supreme Court complained that the district court had essentially nullified N.D.C.C. § 47-01-17. That statute expressly provides that when the trunk of the tree is wholly upon the land of one owner, the tree “belong[s] exclusively to that owner.” The district court’s holding that Herring, in effect, owned the branches above his property was thus contrary to statute. Statutes must be construed as a whole and harmonized to give meaning to related statutes and are to be interpreted in context to give meaning and effect to every word, phrase, and sentence. The interpretation adopted by the district court did not give meaning and effect to that portion of N.D.C.C. § 47-01-17 which provides that the owner of the tree’s trunk “exclusively” owns the entire tree.

Our thanks to the Supreme Court of North Dakota for its comprehensive opinion …

Contrary to the district court’s conclusion that the Massachusetts Rule was more consistent with North Dakota statutory law, the Supreme Court held that the Hawaii Rule more fully gives effect to both statutory provisions. The Hawaii Rule is expressly based upon the concept, embodied in N.D.C.C. § 47-01-17, that the owner of the trunk of a tree that is encroaching on neighboring property owns the entire tree, including the intruding branches and roots. And because the owner of the tree’s trunk is the owner of the tree, the Supreme Court thought he or she should bear some responsibility for the rest of the tree. The Court said, “We think he is duty bound to take action to remove the danger before damage or further damage occurs.”

The Supreme Court also observed that “the Hawaii Rule is the most well-reasoned, fair, and practical of the four generally recognized rules. We first note that the Restatement and Virginia rules have each been adopted in very few jurisdictions, and have been widely criticized as being based upon arbitrary distinctions which are unworkable, vague, and difficult to apply … In fact, the Supreme Court of Virginia has … abandoned the [old] Virginia rule in favor of the Hawaii Rule [in] Fancher…”

The Court said the Massachusetts Rule fostered a “‘law of the jungle’ mentality” among landowners.

The Court also complained that the Massachusetts Rule has been widely criticized as being “unsuited to modern urban and suburban life.” The Massachusetts Rule fosters a “law of the jungle” mentality, the Court said, because self-help effectively replaces the law of orderly judicial process as the only way to adjust the rights and responsibilities of disputing neighbors. The Court observed that while self-help may be sufficient “when a few branches have crossed the property line and can be easily pruned by the neighboring landowner himself, it is a woefully inadequate remedy when overhanging branches break windows, damage siding, or knock holes in a roof, or when invading roots clog sewer systems, damage retaining walls, or crumble a home’s foundation.”

Accordingly, the North Dakota Supreme Court held that “encroaching trees and plants are not nuisances merely because they cast shade, drop leaves, flowers, or fruit, or just because they happen to encroach upon adjoining property either above or below the ground. However, encroaching trees and plants may be regarded as a nuisance when they cause actual harm or pose an imminent danger of actual harm to adjoining property. If so, the owner of the tree or plant may be held responsible for harm caused by it, and may also be required to cut back the encroaching branches or roots, assuming the encroaching vegetation constitutes a nuisance.” The rule does not prevent a landowner, at his or her own expense, from cutting away the encroaching vegetation to the property line whether or not the encroaching vegetation constitutes a nuisance or is otherwise causing harm or possible harm to the adjoining property.

– Tom Root

There are two components to the Massachusetts Rule. The first is easy and universally acclaimed. A landowner owns the portion of branches and roots of a neighbor’s tree that encroach on the landowner’s property and may trim those to his or her heart’s content.

There are two components to the Massachusetts Rule. The first is easy and universally acclaimed. A landowner owns the portion of branches and roots of a neighbor’s tree that encroach on the landowner’s property and may trim those to his or her heart’s content. Grandona v. Lovdal, 21 P. 366, 78 Cal. 611 (Supreme Ct. Cal. 1889). Andrea Grandona owned about 15 acres of farmland next to that of Ole Olson Lovdal. Ole Olson (probably not the children’s chant) had a line of cottonwoods, planted about eight feet apart, running for 500 feet or so just on his side of the boundary, planted about 25 years before by a prior owner.

Grandona v. Lovdal, 21 P. 366, 78 Cal. 611 (Supreme Ct. Cal. 1889). Andrea Grandona owned about 15 acres of farmland next to that of Ole Olson Lovdal. Ole Olson (probably not the children’s chant) had a line of cottonwoods, planted about eight feet apart, running for 500 feet or so just on his side of the boundary, planted about 25 years before by a prior owner.