TRIFLES

There is a wonderful doctrine in the law – and the law is a place where we do not really expect to find anything wonderful – that is known as the rule of de minimis.

There is a wonderful doctrine in the law – and the law is a place where we do not really expect to find anything wonderful – that is known as the rule of de minimis.

Mentioning de minimis gives me an excuse for another shout-out to my sainted Latin teacher from days of yore, Emily Bernges (who instilled in me a love of, if not fluency in, that grand Mother of Languages). But more to the point, the de minimis rule is a necessity: if it didn’t exist, we would have to invent it. Simply put, the rule of de minimis holds that some wrongs we suffer are so slight to be unworthy of recompense.

De minimis is the shortened form of “de minimis non curat lex,” which Emily would have told us means that “the law does not concern itself with trifles.” Queen Christina of Sweden, who occupied the throne in the mid-17th century – and who may have studied under Emily, too, for all we know – favored the more colorful adage, “aquila non captat muscas,” that is, “the eagle does not catch flies.”

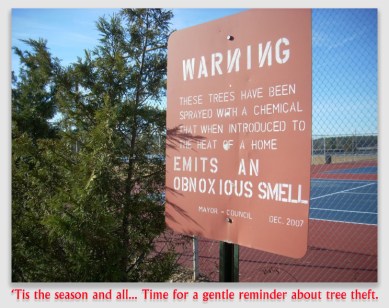

We sometimes think too many plaintiffs want to sue over trifles. The plaintiffs in today’s case, the Bandys, sure did. The neighbors’ trees dropped sap and leaves on their property, and their roots clogged a sewer line. The Bandys did not find that dandy, and so they sued.

The court was aghast. A tree dropping leaves and sap! Who had ever heard of such a thing?

Besides everyone, that is. Trees drip sap and drop leaves and grow roots all the time. It’s just what trees do. Once the law starts making tree owners pay for that, there will be no end to the litigation.

The neighbor’s leaves fell in your yard? Here’s a rake. Deal with it.

The neighbor’s leaves fell in your yard? Here’s a rake. Deal with it.

Bandy v. Bosie (1985), 132 Ill. App. 3d 832, 477 N.E.2d 840. Edith and Chuck Bandy sued their neighbors, Jim and Becky Bosie, complaining that the Bosies’ maple and elm trees dropped sap and leaves on the Bandy’s property, and roots from the trees had damaged the Bosies’ sewer line, causing water to back up in their basement.

The Bosies moved for dismissal, arguing that the Bandys had no cause of action. The court agreed and dismissed the complaint.

The Bandys appealed.

Held: The Bandy complaint failed to allege a nuisance. The court found the Bosies were entitled to grow trees on any or all of their land and their natural growth reasonably resulted in the extension of roots and branches into the adjoining property.

The Bandys argued first that the Bosies should be made to cut down the trees because there was no adequate remedy at law, and the trees were a nuisance. Bosies rejoined that the trees did not constitute a nuisance and that, in any event, the Bandys were not entitled to equitable relief.

Illinois courts have previously held in Merriam v. McConnell (1961), 31 Ill. App. 2d 241, 175 N.E.2d 293, that equity could not be used to control or abate natural forces as if they were a nuisance. Illinois follows the Massachusetts Rule, and holds that an owner is entitled to grow trees on any or all of the land, and their natural growth reasonably will result in the extension of roots and branches into adjoining property. The effects of nature such as the growth of tree roots cannot be held within boundaries; the risk of damage from roots on other lots is inherent in suburban living, and to allow such lawsuits as this one would create litigation over matters that should be worked out between the lot owners.

But in another Illinois decision, Mahurin v. Lockhart (1979), 71 Ill. App. 3d 691, 390 N.E.2d 523, the plaintiff sued an adjoining lot owner for damages resulting from a dead limb falling from the defendant’s tree onto the plaintiff’s property, injuring the plaintiff. The defendant contended she had no liability for damages occurring off of her land resulting from the existence of natural conditions on her land. The appellate court rejected that view, holding that defendant’s theory arose in an era when most land was heavily wooded and sparsely settled, and when the burden of inspecting those larger properties for natural defects would have been unreasonable. In a more modern urban setting, the court considered the burden of inspecting for unsound trees which might injure persons off of the owners’ property to be reasonable.

But in another Illinois decision, Mahurin v. Lockhart (1979), 71 Ill. App. 3d 691, 390 N.E.2d 523, the plaintiff sued an adjoining lot owner for damages resulting from a dead limb falling from the defendant’s tree onto the plaintiff’s property, injuring the plaintiff. The defendant contended she had no liability for damages occurring off of her land resulting from the existence of natural conditions on her land. The appellate court rejected that view, holding that defendant’s theory arose in an era when most land was heavily wooded and sparsely settled, and when the burden of inspecting those larger properties for natural defects would have been unreasonable. In a more modern urban setting, the court considered the burden of inspecting for unsound trees which might injure persons off of the owners’ property to be reasonable.

Here, the complaint is silent as to when and how the trees gained life. That is one reason, the Court said, why the complaint failed to allege a nuisance.

In addition, the Court said, even if counts I and II had stated that the defendant had planted the trees, the counts would still have failed to state a cause of action for injunctive relief. The Court said, “We do not consider trees that drop leaves on neighboring lands or trees that send out roots that migrate to neighboring lands and obstruct drainage to necessarily constitute a nuisance. We recognize that some decisions in other States are to the contrary. We agree with the Merriam court that, under the circumstances here, to permit the falling of leaves or the migration of the roots to give rise to injunctive relief would unduly promote litigation over relatively minor matters. Usually, the damage from the offending leaves would be minimal, and the accurate locating of the source of the offending roots would be difficult and expensive.”

– Tom Root