HERE WE CUT DOWN THE MULBERRY BUSH…

When Mamie’s lights went out, she called the electric company to fix them. The linemen tracked down the problem and fixed it while Mamie was off at Wal-Mart. But while they were there and Mamie wasn’t, the electric workers saw an excellent opportunity to saw… and to get rid of some trees in the utility’s easement across Mamie’s yard that they thought were in the way of the distribution line to Mamie’s house.

When Mamie’s lights went out, she called the electric company to fix them. The linemen tracked down the problem and fixed it while Mamie was off at Wal-Mart. But while they were there and Mamie wasn’t, the electric workers saw an excellent opportunity to saw… and to get rid of some trees in the utility’s easement across Mamie’s yard that they thought were in the way of the distribution line to Mamie’s house.

Mamie returned, shopping bags in hand, to find her mulberry tree had been cut down and cherry tree topped. Naturally, she sued. After all, her trees had not caused the power outage. Nevertheless, the electric company said the tree could have caused the power loss, but for the grace of God, and it relied on its easement to support its right to remove the one tree and permanently stunt the other out of concern that someday they might pose a hazard.

I would have bet a new chainsaw that the electric company was going to win this one, and I can only conclude that it may have been “homered” by the local judge. After all, Mamie was a neighbor, and the big, bad electric co-op was just some faceless out-of-towner. I know of no other way (than possibly an inability to read precedent and engage in reasoned thought) to justify a holding that while the utility had an easement, as well as the duty to maintain the reliability of its lines, it nonetheless could not merely be liable for overzealous trimming but even be socked with treble damages.

Treble damages are only appropriate in Missouri if the malefactor lacks probable cause to believe it owned the land the tree stood on. That test should have been modified to comport with the facts. Consolidated had an easement for the electric lines to cross Mamie’s property, and whether its decision to trim or remove the trees near its lines was correct or not, the decision should have been accorded deference.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at a subsequent Missouri electric company case, where we will see the utility get clobbered despite its desperate reliance on today’s holding.

Segraves v. Consolidated Elec. Coop., 891 S.W.2d 168 (Ct.App. Missouri, 1995). Mamie Segraves sued Consolidated Electric Co-op – her electricity provider – after one of its linemen cut down her mulberry tree and “topped off” her cherry tree.

One summer day, Mamie awoke to find that her electricity was off. She left to go shopping at 9 a.m., and when she returned two hours later, the lights were back on. However, the mulberry and cherry trees in her front yard had been cut down and one branch of her elm tree had been cut off.

One summer day, Mamie awoke to find that her electricity was off. She left to go shopping at 9 a.m., and when she returned two hours later, the lights were back on. However, the mulberry and cherry trees in her front yard had been cut down and one branch of her elm tree had been cut off.

Mamie testified these trees had never interfered with her electrical service before. In the past, Consolidated had asked to trim the trees around her electric lines, and she had always agreed, but it had not done so in the past six years. Mamie estimated the value of the mulberry tree was $2,000.00, and the value of the cherry tree was $500.00.

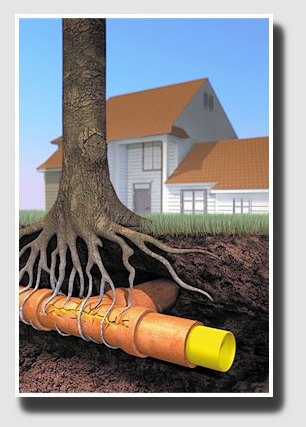

Mitch Hurt, a senior lineman with Consolidated, testified he was called to handle an electrical outage. He tracked the outage to a problem with one of the lines near Mamie’s home, but he could not pinpoint the problem. He had to drive down the road and look at the individual lines to try to find the problem. When he passed the line leading up to her house, he could not see the transformer pole. He stopped and went to inspect her service. He noticed her mulberry tree was very close to the transformer, and so he cut it down “to get it away from the transformer pole.” He also cut off the entire top of a nearby cherry tree because its branches had all grown towards the line. He felt these branches presented a safety hazard because children could easily climb them and reach the power lines. Mitch admitted it may not have been necessary to cut down either of these trees to reinstate electrical service.

Bob Pogue, Jr., Mitch’s boss, testified he told Mitch to trim as much of the trees as he thought was necessary. Bob Jahn, Consolidated’s general manager, testified Mamie knew about the location of the electric lines when she bought the place.

The trial court found in Mamie’s favor and assessed treble damages. Consolidated appealed.

Held: The Co-op had no right to cut the trees, and treble damages were proper.

The trial court did not find Consolidated to be a trespasser because it had the right to enter onto Mamie’s premises to maintain the electric lines. The right to remove limbs that have fallen onto the lines, however, “does not extend to cutting down trees or ‘topping’ trees that are not presently interfering with electrical service without prior consultation with the property owner.” While the mulberry and the cherry trees probably needed to be trimmed, the trial court said, there was no evidence that the mulberry “needed to be cut to a stump and that the cherry needed to be cut back to its major trunks, eliminating all of the fruit-bearing branches.”

Section 537.340 of the Revised Statutes of Missouri allowing for treble damages for the destruction of trees, does not require that a party wrongfully enter upon the property. In fact, the Court of Appeals said, Mamie can recover for wrongfully cutting down trees if she can establish either that Consolidated wrongfully entered her land and cut down the trees, or Consolidated entered her land with consent but exceeded the scope of the consent by cutting down the trees without permission.

While it is true, as Consolidated argued, that a license may be converted into an easement by estoppel if the license holder can establish it spends a great deal of time and money to secure enjoyment of its use, the scope of such an easement nevertheless will be determined by the meaning and intent that the parties give to it. The Court found no history between the parties of cutting down trees, and nothing from which such a right to cut down trees can be implied. Thus, even if Consolidated did acquire an easement by estoppel, it exceeded the scope of the easement by cutting down Mamie’s mulberry and cherry trees.

The utility also argued it was required by law to trim or remove the trees to ensure safety. Under the National Electrical Safety Code, Consolidated argued, it was required to trim or remove trees that may interfere with ungrounded supply conductors should be trimmed or removed, and where that was not practical, the conductor should be separated from the tree with proper materials to avoid damage by abrasion and grounding of the circuit through the tree. Consolidated maintained it had the authority to remove Mamie’s trees according to the Code because there was substantial evidence showing limbs of both trees had been burned by electricity, the mulberry tree was blocking the transformer pole, and the children living nearby could have easily climbed either tree and reached the live electric wires.

The utility also argued it was required by law to trim or remove the trees to ensure safety. Under the National Electrical Safety Code, Consolidated argued, it was required to trim or remove trees that may interfere with ungrounded supply conductors should be trimmed or removed, and where that was not practical, the conductor should be separated from the tree with proper materials to avoid damage by abrasion and grounding of the circuit through the tree. Consolidated maintained it had the authority to remove Mamie’s trees according to the Code because there was substantial evidence showing limbs of both trees had been burned by electricity, the mulberry tree was blocking the transformer pole, and the children living nearby could have easily climbed either tree and reached the live electric wires.

The Court rejected that, holding that Consolidated failed to show that the Code applied here because it failed to present evidence that the electrical wires leading to Mamie’s home were “ungrounded supply conductors.” Further, even if the Code applied, it gives electric companies two options, to trim or to remove the trees. The trial court found it was unnecessary to remove the trees in this case.

Not to be deterred, Consolidated also argued it was obligated to remove the trees because it had a non-delegable duty to maintain a safe clearance around its electrical lines. “Although Consolidated was required to exercise the highest degree of care in maintaining its electrical wires,” the Court said, “it was not required to remove the trees surrounding them, and it exceeded its authority by doing so.”

Section 537.340 of Missouri Revised Statutes holds that if any person shall cut down, injure, or destroy or carry away any tree placed or growing for use, shade, or ornament, or any timber, rails, or wood standing, being or growing on the land of any other person, the person so offending shall pay to the party injured treble the value of the things so injured, broken, destroyed, or carried away, with costs.

The Court noted that a person can only fell trees wrongfully in one of two ways: he can enter the land wrongfully and fell the trees, or he can enter with the landowner’s consent and then exceed the scope of that consent by felling trees without permission. While the statute limits damages recoverable to single damages in certain cases, such as where it appears the defendant has probable cause to believe that the land on which the trespass is alleged to be committed, or that the thing so taken, carried away, injured, or destroyed, is his own. It was up to Consolidated to prove it had such probable cause.

The determination of whether the defendant proved probable cause existed rests with the trial judge. Here, the Court said, “the trial judge did not abuse his discretion in finding Consolidated did not have probable cause” to believe it had the right to cut down Mamie’s trees.

– Tom Root

Yesterday, we read about Mamie Segraves, who successfully sued an electric utility because its workers determined that trees within its easement posed a risk to the distribution lines and that one should be removed and the other topped.

Yesterday, we read about Mamie Segraves, who successfully sued an electric utility because its workers determined that trees within its easement posed a risk to the distribution lines and that one should be removed and the other topped. Held: Greg’s suit was reinstated.

Held: Greg’s suit was reinstated.