ROADBLOCKS

When we were kids, we watched Broderick Crawford in that black-and-white police classic “Highway Patrol.” Every week, the full-figured, squinty-eyed Crawford — as highway patrol chief Dan Matthews — would pursue the bad guys in his finned Plymouth police coupe interceptor, usually catching the malefactors after setting up roadblocks all over California and barking “10-4” into his mic several times.

When we were kids, we watched Broderick Crawford in that black-and-white police classic “Highway Patrol.” Every week, the full-figured, squinty-eyed Crawford — as highway patrol chief Dan Matthews — would pursue the bad guys in his finned Plymouth police coupe interceptor, usually catching the malefactors after setting up roadblocks all over California and barking “10-4” into his mic several times.

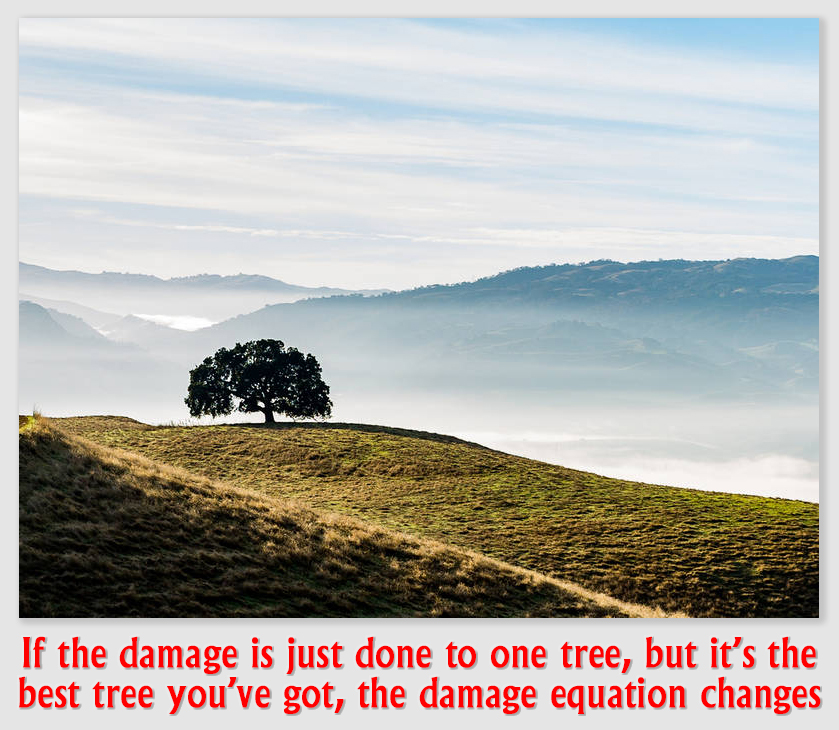

We loved that show. But Dan Matthews and his troopers had nothing on the political subdivisions in today’s case. When Mr. Bright’s car was crushed by a tree limb while he was driving down a road in the Village of Great Neck Estates, he got himself a lawyer and sued the town and the county. They immediately set up roadblocks worthy of the best 50s-era cop show.

The case seemed pretty straightforward. The plaintiffs argued that the county and village had had notice that the tree was defective. That hardly matters, the defendants retorted, because you, Mr. Bright, never gave us written notice that the tree was defective. The Administrative Code of Nassau County requires that you do so. As for your passenger, who also sued, she had not shown that she had suffered a serious injury, as required by the state’s insurance law. Not very bright, Mr. Bright, the defendants argued smarmily.

Fortunately, the plaintiff was Bright enough. The appellate court made short work of the county’s motion. The county’s prior-notice requirement, it ruled, related to physical deficiencies in roads and bridges, obvious problems that nonetheless might not be known to county officials. If such a requirement were applied to the trees alongside the road, there might as well be no duty imposed on an owner to inspect trees to begin with. Motorists would have had to pick the tree likely to fall on them and write to the county about it before it fell. Lots of luck with that.

Besides, while a gaping pothole in the road is obvious to passing motorists, the same can’t be said for a diseased tree, which is not especially susceptible to drive-by inspections.

As for the state insurance law, the requirement that a passenger prove serious injuries is intended to cut down on suits against other drivers. This case wasn’t about a county employee being reckless behind the wheel, but instead, the case was a simple one of premises liability. The County owned the highway and the tree next to it; the tree was defective. Voila, a lawsuit.

So the Court cleared the first set of roadblocks for Plaintiff Bright. So, this is Broderick Crawford, saying, “See you in court.”

Bright v. Village of Great Neck Estates, 863 N.Y.S.2d 752, 54 A.D.3d 704 (N.Y.A.D. 2 Dept., 2008). Mr. Bright suffered personal injuries when a tree limb fell on the car in which he was traveling in the Village of Great Neck Estates. Bright and his passenger sued, alleging that the accident was proximately caused by Nassau County’s negligence in failing to remove a dead or diseased tree.

The County moved for a summary judgment dismissing the complaint on the grounds that Bright had not complied with the prior written notice requirement set forth in § 12-4.0(e) of the Administrative Code of Nassau County and that the County lacked both actual and constructive notice of the purported hazard. The County also sought to dismiss the complaint by Bright’s passenger on the ground that she did not sustain a serious injury within the meaning of Insurance Law §5102(d). The trial court denied the County’s motion for summary judgment.

Held: Denial of the summary judgment motion was proper. The Court observed that prior written notice statutes are intended to apply to actual physical defects in the surface of a street, highway, or bridge of a kind that do not immediately come to the attention of the municipal officials unless they are given actual notice. Here, the Court held, the defect was no more obvious to the motorist than it was to the county, and probably much less so. The prior written notice statute was held not to apply to trees.

Furthermore, the Court said, the County failed to establish that it lacked actual and constructive notice of the hazard tree alleged to exist in this case.

Finally, the Court said, Mr. Bright’s passenger was not required to establish that she suffered a serious injury because she did not allege the County was negligent in the use or operation of the car (which is what the statute addresses). Instead, the allegations against the County related to premises liability. The County doesn’t qualify as a covered person within the meaning of the Insurance Law, which was written to stop the flood of staged car accident lawsuits clogging New York courts.

– Tom Root