TOPPER

We have seen our share of “obstructed view” cases, in which landowners were not liable because their vegetation obscured traffic signs.

But what if the landowner does something to the tree or vegetation to exacerbate the situation? Is that even possible? More to the point for a negligence calculus, does a landowner owe a duty to motorists?

But what if the landowner does something to the tree or vegetation to exacerbate the situation? Is that even possible? More to the point for a negligence calculus, does a landowner owe a duty to motorists?

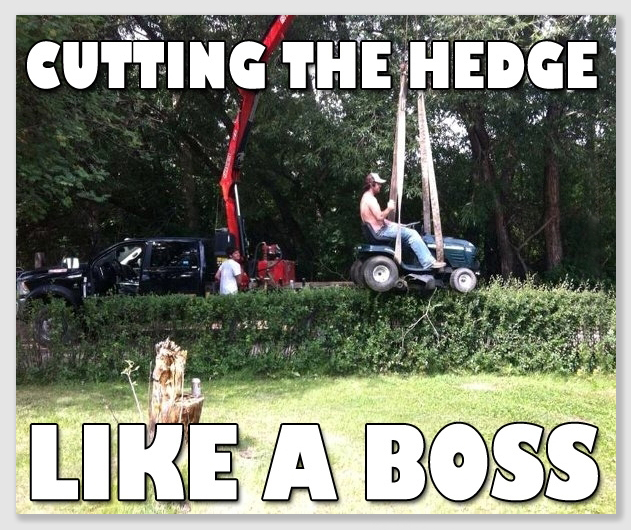

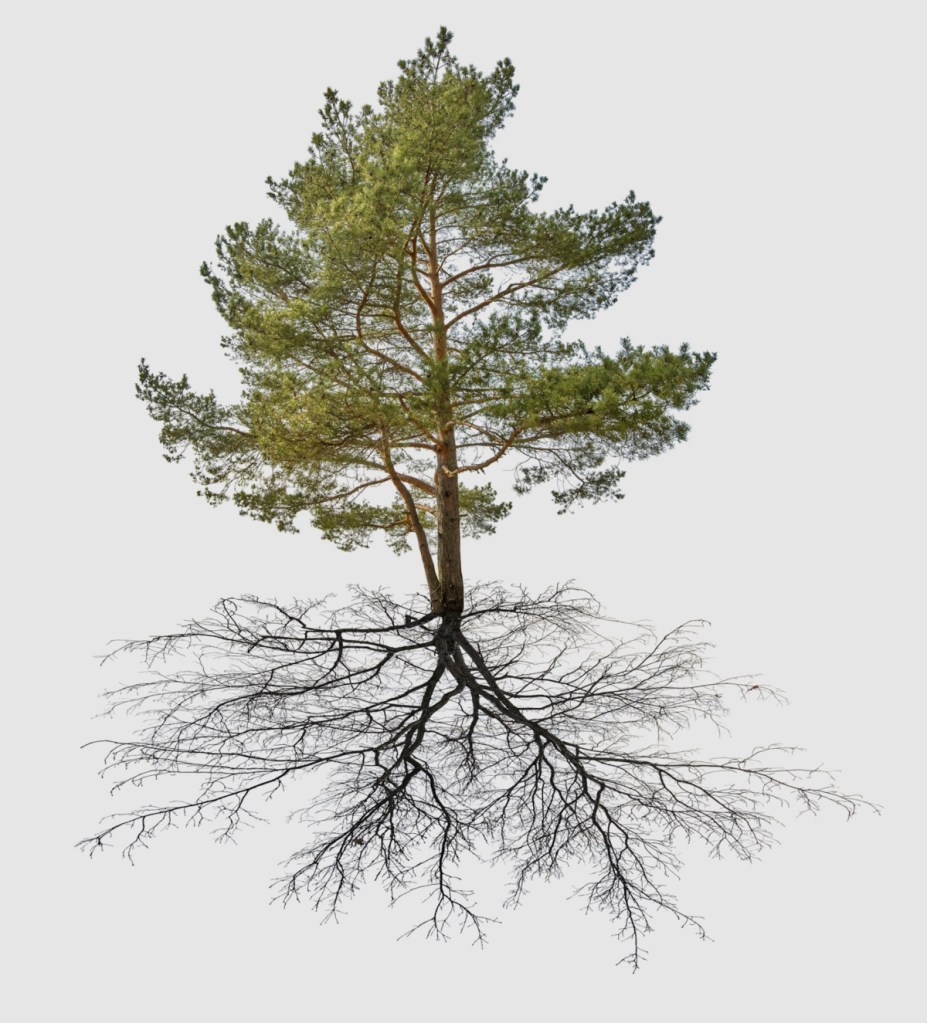

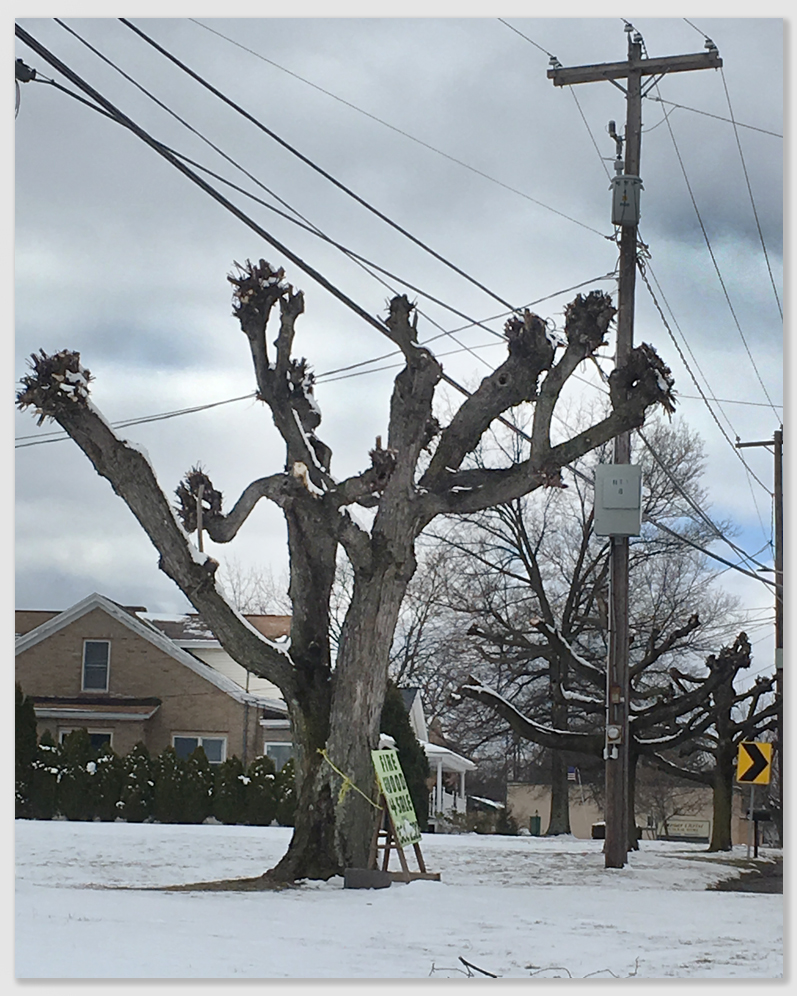

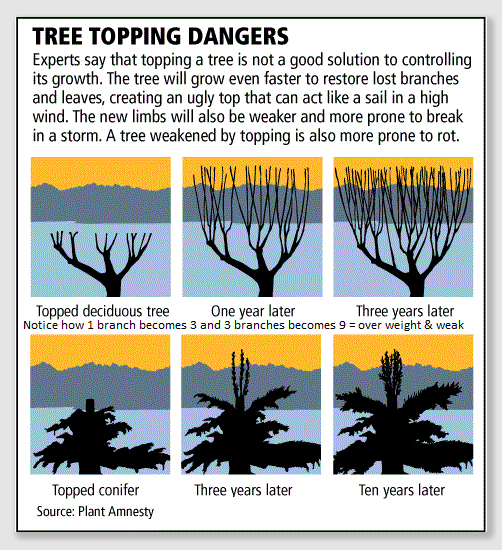

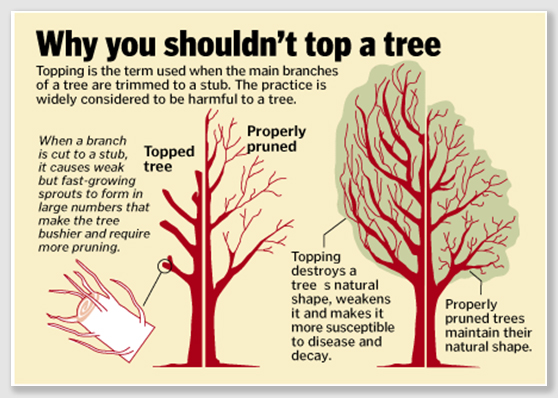

Today’s case asks just that question. A utility company that took the easy way out, and simply topped a pine tree standing under one of its lines. Topping is a lousy way to trim a tree. No self-respecting arborist would have anything to do with it. And, it turns out, that topping did not stop the tree from growing. It simply forced the tree to grow out instead of up.

Iglehart v. Bd. of County Comm’rs, 60 P.3d 497 (Supreme Ct. Okla. 2002). Brenda Iglehart failed to stop at a county road intersection where crossing traffic had the right-of-way. She was broadsided. She sued everyone she could think of, including the Board of County Commissioners for negligent maintenance of the road, and – relevant to this appeal – Verdigris Valley Electric Cooperative. She alleged Verdigris, which owned an easement alongside the road, contending it negligently maintained a white pine tree by “topping” it in order to keep the tree limbs from interfering with electric lines. By so doing, Brenda said, Verdigras caused the tree to grow laterally and more densely, obscuring the stop sign. According to plaintiffs, Verdigras owed a duty of care to motorists traveling on the adjoining roadway, or at least a duty to warn of a hazardous condition within its control, and that its breach of this duty directly caused Brenda’s injuries.

The trial court granted summary judgment to Verdigris and the Commissioners). The Court of Civil Appeals reversed the summary judgment for the Board but upheld summary judgment in favor of Verdigris. The appellate court held that a utility company does not owe a duty of care to travelers on roads adjacent to its power lines which are under its maintenance.

Brenda appealed to the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

Held: A utility company owes a duty of care to traveling motorists on adjoining roads when its substandard maintenance of trees could foreseeably cause danger to the public.

The Court observed that to establish negligence liability for an injury, Brenda must prove that (1) Verdigris owed her a duty to protect her from injury, (2) Verdigris breached that duty, and (3) its breach was a proximate cause of Brenda’s injuries. The burden is not cast upon Brenda to establish that Verdigris was negligent in order to escape its motion for summary judgment. Rather, to avoid trial for negligence, Verdigris must establish through unchallenged evidentiary materials that, even when viewed in a light most favorable to Brenda, no disputed material facts exist as to any material issues and that the law favors Verdigris.

Verdigris contends that (1) no duty existed; that (2) if a duty existed, the company did not breach it, and that even if it had, (3) its actions were not a proximate cause of Brenda’s injuries.

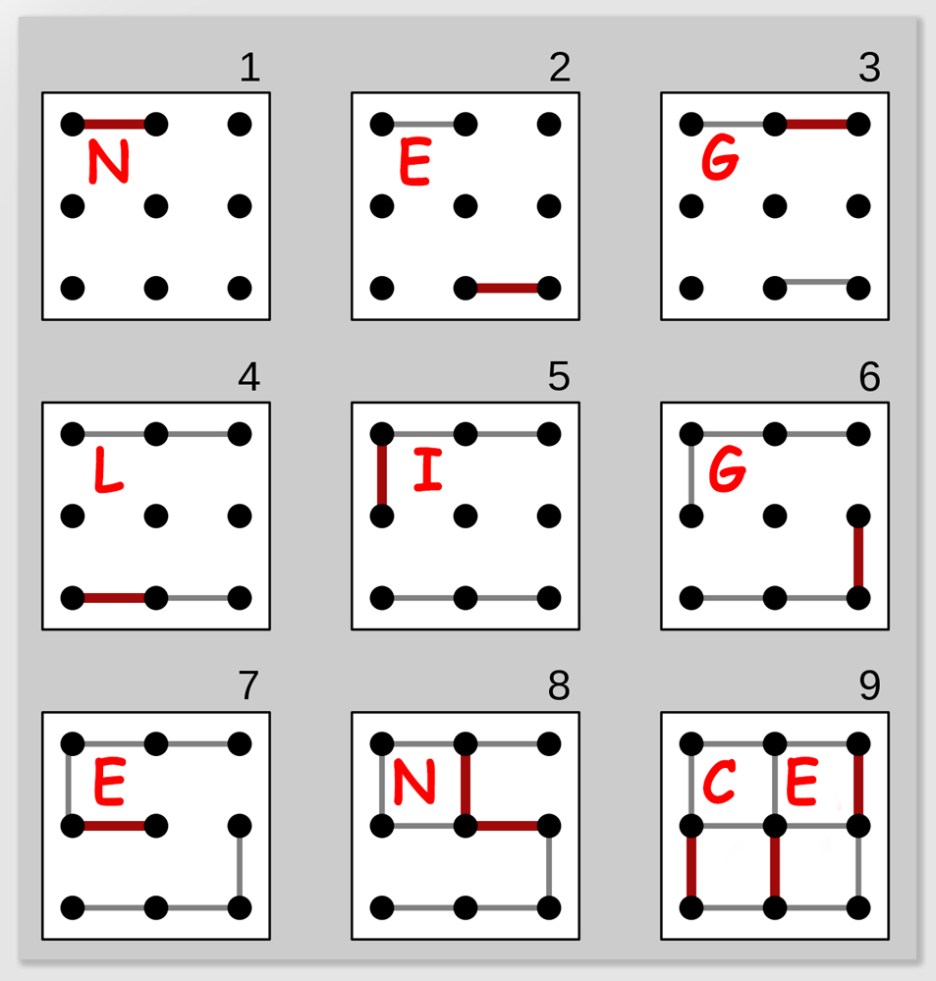

The threshold question for negligence suits is whether a defendant owes a plaintiff a duty of care. “We recognize,” the Court said, “the traditional common-law rule that whenever one person is by circumstances placed in such a position with regard to another, that, if he (she) did not use ordinary care and skill in his (her) own conduct, he would cause danger of injury to the person or property of the other, a duty arises to use ordinary care and skill to avoid such danger.” Among a number of factors used to determine the existence of a duty of care, the most important consideration is foreseeability. Generally, a defendant owes a duty of care to all persons foreseeably endangered by his conduct concerning all risks which make the conduct unreasonably dangerous. Foreseeability establishes a “zone of risk,” which is to say that it forms a basis for assessing whether the conduct creates a generalized and foreseeable risk of harming others.

The question of whether a duty is owed by a defendant is one of law; a breach of that duty is a question of fact for the trier. Here, the Court held that a utility company indeed owes a duty of care to traveling motorists on adjoining roads when its substandard maintenance of trees could foreseeably cause danger to the public. Citing the Oregon Supreme Court’s decision in Slogowski v. Lyness, the Court ruled it was potentially foreseeable to a utility company that a tree it maintained could cause a hazardous condition to motorists on an adjacent roadway. Once having undertaken the task of trimming and inspecting trees within its easement, a party must act reasonably in the exercise of that task.

In this case, the Court said, Brenda has raised a disputed issue of fact regarding the foreseeability of the injuries she suffered, sufficient to avoid summary process. According to the affidavit of her expert witness, James R. Morgan, the white pine tree in question had been “topped.” The main tree trunk has been cut off in the upper quadrant of the tree. Once this occurs, the upward growth is halted, and the tree instead increases density and limb growth. These results, the affidavit stated, are particularly true for the type of pine tree in question and are common knowledge among those who cut trees.

In this case, the Court said, Brenda has raised a disputed issue of fact regarding the foreseeability of the injuries she suffered, sufficient to avoid summary process. According to the affidavit of her expert witness, James R. Morgan, the white pine tree in question had been “topped.” The main tree trunk has been cut off in the upper quadrant of the tree. Once this occurs, the upward growth is halted, and the tree instead increases density and limb growth. These results, the affidavit stated, are particularly true for the type of pine tree in question and are common knowledge among those who cut trees.

Verdigris challenged the certainty with which the expert made his determination, but at this stage of summary process review, the Court said, “We must view facts in the light most favorable to the plaintiff. Mindful of this rule, we hold that – given the proximity of the tree to the stop sign and the common-sense notion that without a visible stop sign, an intersection, such as that here in question, poses an obvious hazard” Brenda had raised a disputed issue of material fact as to the foreseeability of the accident arising from the action of Verdigris. “Foreseeability must hence be left for a jury evaluation.”

– Tom Root