SHOW ME WHERE IT HURTS

At common law, it was always good to be king. Because of a cool crown and a nice castle to live in, the king could not be sued by his subjects without his permission. This concept is known as “sovereign immunity.” Sadly, the concept never extended to a private citizen. This is hardly surprising. A sovereign usually takes care of itself, not its subjects. However, where social utility calls for it, states have extended immunity to the common man and woman.

At common law, it was always good to be king. Because of a cool crown and a nice castle to live in, the king could not be sued by his subjects without his permission. This concept is known as “sovereign immunity.” Sadly, the concept never extended to a private citizen. This is hardly surprising. A sovereign usually takes care of itself, not its subjects. However, where social utility calls for it, states have extended immunity to the common man and woman.

The most obvious of these kinds of statutes are “Good Samaritan” laws in the United States and Canada, legislation that shields from liability those who choose to aid the injured or ill. The laws are intended to reduce bystanders’ hesitation to assist out of fear of being sued for unintentional injury or wrongful death.

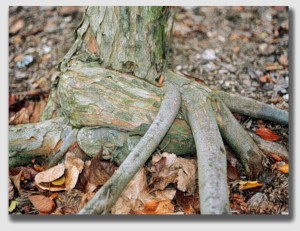

Of particular interest to us is the class of immunity laws known as recreational user statutes. Recreational user statutes, although they vary from state to state, generally create tort immunity for landowners who open their land to the public free of charge for recreational use. If you let people wander your woods, you aren’t liable if they step into a woodchuck hole. The statutes serve a public purpose. If you had to shell out every time Bertha Birdwatcher tripped over an exposed root, then you would respond by posting your land to prohibit hikers, campers, and boaters.

The public benefits from getting back to nature are obvious. In fact, in many cases, the recreational use statutes apply to governments as well, such as the nice little park a small town maintains around the municipal reservoir. Recreational use acts are intended to encourage landowners to offer free use of their land to the public for recreational purposes to preserve and utilize the state’s natural resources.

The foregoing has not rid us of creative lawyers. We all dislike crafty litigators (at least, until we need one ourselves). Today’s case – which is, unfortunately, very timely – concerns a little girl who was camping with her family in a California state park. During the night, a tree 60 feet from her campsite fell, hitting the family’s tent and leaving the 3-year-old with severe brain damage. A sad state of affairs to be sure, one that makes the plaintiff a very sympathetic party.

The family’s crafty litigator figured out that the California recreational use statute only applied to unimproved land. The tree was on unimproved land, but the campsite it fell on was improved. The plaintiff’s attorney argued that because the injury occurred on improved land, California was liable for little Alana’s serious injuries.

Much of the decision turned on whether one measures “unimproved area” from where the defect is located, or where the injury occurs. Remember President Clinton? It depends on what the meaning of “is” is. Often on the heads of such semantic pins an entire case can turn. Here, it did not matter whether Alana was on improved property when she was hurt. It mattered whether the tree that fell was standing on improved property because it toppled.

Much of the decision turned on whether one measures “unimproved area” from where the defect is located, or where the injury occurs. Remember President Clinton? It depends on what the meaning of “is” is. Often on the heads of such semantic pins an entire case can turn. Here, it did not matter whether Alana was on improved property when she was hurt. It mattered whether the tree that fell was standing on improved property because it toppled.

Alana M. v. State of California, 245 Cal. App. 4th 1482 (Ct.App. Calif. 1st Div., 2016). Three-year-old Alana M. was camping with her family in Portola Redwoods State Park, which is owned by the State and is located in an existing forest in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

As Alana’s family slept in their tent, a tanoak tree fell directly on the campsite and struck Alana on her head, resulting in brain damage. The tree was growing on a hillside about 60 feet away from the Campsite. Tanoak trees are indigenous to the area. The nearest man-made object to the tree, before it fell, was a picnic table at Campsite 42, which was about 30 feet away. The tree broke about three feet from the ground.

The State had built improvements and amenities in the Park, including roads, campsites, hiking trails, a visitor center, and various other buildings. The amenities are scattered throughout the park, occupying about 5 percent of the parkland.

Tanoak tree

Alana sued the State, asserting claims of premise liability under Government Code § 815.2, and dangerous condition of public property under Government Code § 835.2. She said the tree that fell had rot, a cavity, a hatchet wound, and it “was overextended with poor taper.” Alana alleged the State negligently failed to properly maintain Campsite 41 “and its environs” and negligently failed to warn of the danger of falling trees and, further, the State knew or should have known of the structural defects of the tree that fell and injured her.

The State argued it was immune from liability under Government Code § 831.2 because Alana was injured by a natural condition of unimproved public property. The State pointed to Alana’s concession that the fallen tree “was an object of nature.” Alana maintained there was a dispute of fact as to whether the tree that injured her was on improved or unimproved public property. She relied on the Department’s Tree Hazard Program, which established a process for identifying and removing dangerous trees from developed areas. In Portola Redwood State Park, the Tree Hazard Program applied to all the trees in the campgrounds, including the trees that fell. Under the program, the campground was subject to biannual tree inspections, and periodically hazardous trees were removed. Alana cited language from a Department operations manual that said the Tree Hazard Program applied “solely within the developed areas of all parks operated by the Department.” The publication thus raised a question of whether the entire area of the campground, including the tree that injured her, was “improved public property” outside the ambit of § 831.2.

The trial court granted summary judgment to the State, and Alana appealed.

Held: Alana failed to raise an issue of fact as to whether the tree was on “unimproved public property” for purposes of Government Code § 831.2, and the State’s “natural condition immunity” applied.

Government Code § 831.2, commonly referred to as the “natural condition immunity,” provides that “[n]either a public entity nor a public employee is liable for an injury caused by a natural condition of any unimproved public property, including but not limited to any natural condition of any lake, stream, bay, river or beach.” The statute provides for absolute immunity, intending “to encourage public entities to open their property for public recreational use” by providing immunity “because the burden and expense of putting such property in a safe condition and the expense of defending claims for injuries would probably cause many public entities to close such areas to public use.” The natural condition immunity applies even “where the public entity had knowledge of a dangerous condition which amounted to a hidden trap,” and even “where a governmental entity voluntarily assumes a protective service” – such as the Department’s Tree Hazard Program – that induces “public reliance, and through the negligent performance of that protective service concurrently causes a member of the public to be victimized by a dangerous, latent, and natural condition.”

It is also the rule that “improvement of a portion of a park area does not remove the immunity from the unimproved areas.” Otherwise, the Court said, the immunity of an entire park area would be wiped out even if only a small portion was improved.

Finally, because the phrase “of unimproved public property” in § 831.2 modifies the “natural condition” that caused the injury, the relevant issue for determining whether the immunity applies is the character (improved or unimproved) of the property at the location of the natural condition, not at the location of the injury.

Alana did not dispute the tree that injured her was a natural condition under § 831.2. Portola Redwoods State Park is an existing natural forest and tanoaks are indigenous. There is no evidence of any artificial change in the tree’s condition nor any evidence of artificial improvements to the tree. Alana argued there was a causal link between the improvements to the campsites and the dangerousness of the tree because “the campsites increased the likelihood that humans would be present when a tree fell in the area and hence increased the likelihood that one of them might be injured.” But, the Court said, the public is always more likely to visit public lands with amenities such as parking, informational signs and maps, toilets, lifeguards, fire rings, hiking trails, picnic tables, campsites, and the like, than similar public lands with no amenities. Such amenities do not abrogate the natural condition immunity for areas that are not improved. If Alana’s argument were to prevail, this would seriously thwart accessibility and enjoyment of public lands by discouraging the construction of such improvements as restrooms, fire rings, campsites, entrance gates, parking areas, and maintenance buildings.

Alana did not dispute the tree that injured her was a natural condition under § 831.2. Portola Redwoods State Park is an existing natural forest and tanoaks are indigenous. There is no evidence of any artificial change in the tree’s condition nor any evidence of artificial improvements to the tree. Alana argued there was a causal link between the improvements to the campsites and the dangerousness of the tree because “the campsites increased the likelihood that humans would be present when a tree fell in the area and hence increased the likelihood that one of them might be injured.” But, the Court said, the public is always more likely to visit public lands with amenities such as parking, informational signs and maps, toilets, lifeguards, fire rings, hiking trails, picnic tables, campsites, and the like, than similar public lands with no amenities. Such amenities do not abrogate the natural condition immunity for areas that are not improved. If Alana’s argument were to prevail, this would seriously thwart accessibility and enjoyment of public lands by discouraging the construction of such improvements as restrooms, fire rings, campsites, entrance gates, parking areas, and maintenance buildings.

California’s natural forests provide great natural beauty and recreational opportunities along with natural hazards. Alana points to “evidence that all trees eventually fail” and “the simple fact that the tree that fell was 86 feet tall and only 60 feet from Campsite 41” as evidence the tree that injured her was on improved property. This evidence, however, only shows there is risk associated with spending time among the trees of Portola Redwoods State Park; it does not show the tree that fell was on improved property. The Court said, “We do not believe the State became a guarantor of public safety by providing campsites.”

Alana argued the fact the tree was subject to the Tree Hazard Program “leads ineluctably to the inference that the [Department] considered that tree to be standing on improved property within the meaning of § 831.2.” Even if this were so, the Court said, Alana offered no authority for the proposition a defendant’s belief regarding a legal conclusion creates a triable issue on the matter in the absence of any evidence supporting that legal conclusion. Here, there is no evidence raising a triable issue of fact as to whether (1) there was a physical change in the condition of the property where the tree grew or (2) an improvement or human conduct contributed to the danger of the tree. The Department’s belief that the tree was on improved property is not competent evidence on either of these issues.

Essentially, the Court concluded, Alana’s position is she was entitled to a campsite in the forest safe from falling trees, but this “is exactly the type of complaint § 831.2 was designed to protect public entities against.”

– Tom Root

Smith v. Huron, 2007-Ohio-6370, 2007 Ohio App. LEXIS 5589, 2007 WL 4216133 (Ohio App. Erie Co., Nov. 30, 2007). Four people died at Nickel Plate Beach on July 10, 2002, when another person screamed for help from the water. The four entered the water to save her, but although she survived, the four would-be rescuers drowned in the windswept waters of Lake Erie.

Smith v. Huron, 2007-Ohio-6370, 2007 Ohio App. LEXIS 5589, 2007 WL 4216133 (Ohio App. Erie Co., Nov. 30, 2007). Four people died at Nickel Plate Beach on July 10, 2002, when another person screamed for help from the water. The four entered the water to save her, but although she survived, the four would-be rescuers drowned in the windswept waters of Lake Erie. Held: The City of Huron was immune from liability. The survivors claimed that O.R.C. §2744, Ohio’s Political Subdivision Tort Liability Act, did not confer immunity on Huron. Indeed, under O.R.C. 2744.02(B), in some situations, a political subdivision can be held liable for damages in a civil suit arising from injury, death, or loss to persons or property allegedly caused by any act or omission of the political subdivision or its employees in connection with a governmental or proprietary function.

Held: The City of Huron was immune from liability. The survivors claimed that O.R.C. §2744, Ohio’s Political Subdivision Tort Liability Act, did not confer immunity on Huron. Indeed, under O.R.C. 2744.02(B), in some situations, a political subdivision can be held liable for damages in a civil suit arising from injury, death, or loss to persons or property allegedly caused by any act or omission of the political subdivision or its employees in connection with a governmental or proprietary function.