THINGS ARE SELDOM WHAT THEY SEEM

Buttercup: Things are seldom what they seem,

Skim milk masquerades as cream;

Highlows pass as patent leathers;

Jackdaws strut in peacock’s feathers.Captain: Very true,

So they do.Things are Seldom What They Seem

(duet with Buttercup and Capt. Corcoran)

Gilbert & Sullivan, H.M.S. Pinafore

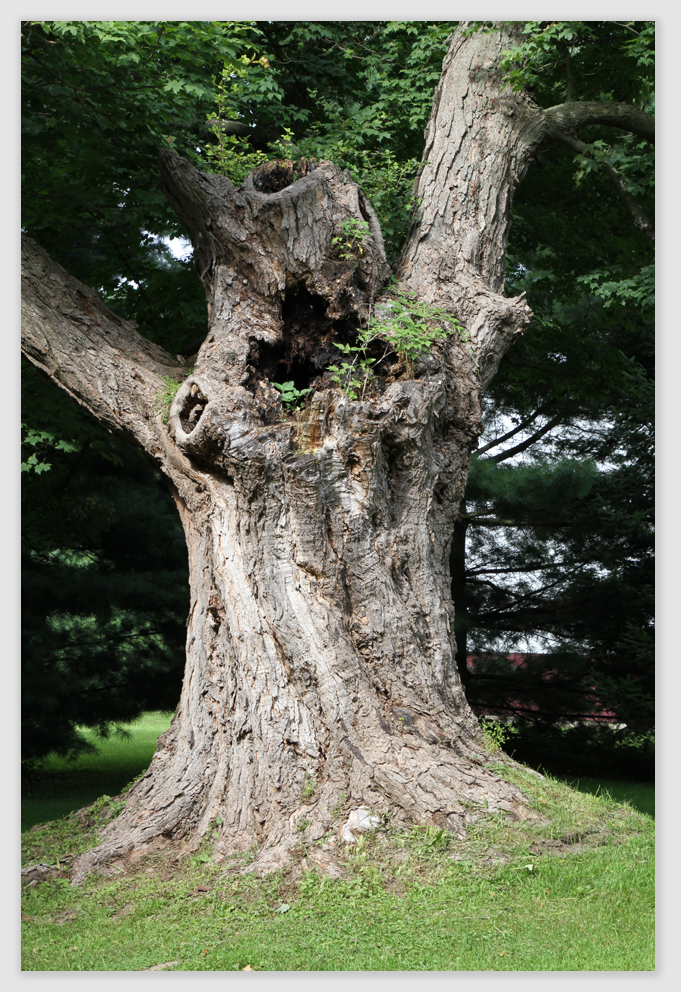

So property rights are as dry as toast? Well, maybe, depending on whether it’s your ox that’s getting gored. Consider Marvin Brandt. This hard-working son of a hard-working lumberman is a Wyoming rancher. His father, who started in the 1930s as a lowly sawmill worker, ended up owning the place. Marvin worked at his Dad’s mill as a youth, and he ended up running the mill himself.

So property rights are as dry as toast? Well, maybe, depending on whether it’s your ox that’s getting gored. Consider Marvin Brandt. This hard-working son of a hard-working lumberman is a Wyoming rancher. His father, who started in the 1930s as a lowly sawmill worker, ended up owning the place. Marvin worked at his Dad’s mill as a youth, and he ended up running the mill himself.

The year of our Lord 1976 was an important year. It was the America’s Bicentennial. I had this hot little Datsun 240Z, a rust bucket if ever there was one, but she screamed. Marvin bought the sawmill from his father. Congress repealed the General Railroad Right-of-Way Act of 1875. And Marvin bought a nice chunk of land for his sawmill – not to mention plenty of standing timber – from the U.S. Forest Service. He obtained it through a procedure known as a land patent, in which the Government deeds its rights in land to private property holders.

It was a pretty good deal, sold to Marvin without many restrictions. There was an easement for the Laramie, Hahn’s Peak and Pacific Railroad, but that wasn’t much of a problem for him. Easements weren’t such an impediment, he thought. But then, things are seldom what they seem…

Buttercup: Black sheep dwell in every fold;

All that glitters is not gold;

Storks turn out to be but logs;

Bulls are but inflated frogs.Captain: So they be,

Frequentlee.

The Union Pacific had tracks running through the property that Marvin bought. He wasn’t alone in this: some 30 other people bought Government land subject to the UP’s railroad right-of-way. The right of way originally was obtained by LHP&P in 1908, pursuant to the 1875 Act. The 200-foot-wide right of way meanders south from Laramie, Wyoming, through the Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest, to the Wyoming-Colorado border.

After the railroad line was abandoned, the Government claimed that the land underlying the old track bed had reverted to Uncle Sam. The Washington bureaucrats had plans to turn the route into a hiking trail. When the Government sued to quiet title on the right-of-way, it named all 31 landowners as defendants. None of them owned more than 3 acres affected by the right-of-way, and none of them mounted a defense. They all threw up their hands, folded quietly, and let the U.S. of A. have its way.

After the railroad line was abandoned, the Government claimed that the land underlying the old track bed had reverted to Uncle Sam. The Washington bureaucrats had plans to turn the route into a hiking trail. When the Government sued to quiet title on the right-of-way, it named all 31 landowners as defendants. None of them owned more than 3 acres affected by the right-of-way, and none of them mounted a defense. They all threw up their hands, folded quietly, and let the U.S. of A. have its way.

Except Marvin.

Marvin may be one of your rugged Wyoming individualists. He may be ornery. But one thing was for sure – unlike the others, Marvin had over 85 acres affected by the old roadbed. Nearly a half-mile stretch of the right of way crossed Marvin’s land, covering ten acres of his parcel and affecting 75 more. In other words, this wasn’t chump change.

The Government, as administrations of either political party are wont to do, tried to steamroll Marvin. The Feds claimed that the LHP&P had owned the land under its rails, subject only to a reversionary interest in the Government if it ever abandoned the line. Therefore, Uncle Sam claimed, when the tracks came out, ownership of the property reverted to the U.S. Forest Service.

The District Court agreed that the 1875 Act and the land patent were not models of clarity, but the Government won anyway. The Court of Appeals reversed. The Government, seeing its Golden Goose about to be slaughtered, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supremes, by a resounding 8-1 decision, held that “things are seldom what they seem.” The right-of-way granted to the railroad might seem like a transfer of the land in fee simple, subject only to being returned to the Government if the rail line was abandoned. But it was really only an easement, meaning that the land patent to Marvin had transferred all ownership to him, subject only to the easement. When the easement vanished, the land was all his.

Marvin stood to lose a big chunk of land – a 200′ wide strip along the north-south road on the west side of his property – to the Government.

The Government’s insurmountable hurdle was its own cuteness. Back in the 1920s, the railroad had planned to drill for oil along the right-of-way (remember Teapot Dome?). The Government had opposed it, claiming that it owned the oil. The railroad, Uncle Sam claimed, only owned an easement. The land (and the wealth under it) belonged to the Feds. The case ended up in the Supreme Court, where the Government won.

But now, the Government argued that things aren’t what they seem to be, and – for that matter – what they seemed to be back in 1942. The Forest Service never owned the land under the railroad when it gave Marvin the land patent. Instead, the railroad did, and the Government didn’t get it back until well after it had sold the rest to Marvin. The 1942 decision must be wrong, to the extent it applied to anything other than oil rights. Thus, the railroad right-of-way reverted to the U.S. Forest Service in 1988, 12 years after the rest of the land was sold to Marvin.

The Supreme Court was not amused. Applying the ancient legal principle that “you dance with the one that brung ya,” the Justices ruled that the Government persuaded the Court in 1942 that the railroad right-of-way was just an easement, and it wasn’t going let the Government change its position now just because it suited it to do so. Alas, the Justice Department (and this is a fault that has belonged to predecessor administrations, Republican or Democrat) all too often has no compunction about changing its arguments for convenience when it should adhere to them for principle. This time, it didn’t work.

Only Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented, in an opinion that seemed peculiarly strained. Anxious to serve the back-to-nature folks who enjoyed Federally-funded hiking and biking trails, she argued that the 1942 case was only about subsurface rights – which seems to us to be a distinction without a difference – and, anyway, the Brandt decision would hurt the rails-to-trails movement and result in a lot of litigation as private landholders sought to get what was rightfully theirs. This may be so, but cost and inconvenience shouldn’t drive Supreme Court opinions. The law should.

So the right-of-way that the Government once said was an easement but now seemed to be something else, really was just an easement … as it had been all along.

Buttercup: Drops the wind and stops the mill;

Turbot is ambitious brill;

Gild the farthing if you will,

Yet it is a farthing still.Captain: Yes, I know.

That is so.

Marvin M. Brandt Revocable Trust v. United States, 572 U.S. 93, 134 S.Ct. 48, 186 L.Ed.2d 962 (2014): The General Railroad Right-of-Way Act of 1875 provides railroad companies “right[s] of way through the public lands of the United States,” 43 U.S.C. § 934. One such right-of-way, created in 1908, crosses land that the Government conveyed to the Brandt family in a 1976 land patent. That patent stated that the land was granted subject to the right of way, but it did not specify what would occur if the railroad relinquished those rights.

A successor railroad abandoned the right of way with federal approval. The Government sought a declaration of abandonment and an order quieting its title to the abandoned right-of-way, including the stretch across the Brandt patent. Brandt argued that the right of way was a mere easement that was extinguished upon abandonment.

The district court quieted title in the government. The Tenth Circuit affirmed.

The Supreme Court reversed.

It held that the right-of-way was an easement terminated by abandonment, leaving Brandt’s land unburdened. The Court noted that in the 1942 Supreme Court decision in Great Northern R. Co. v. United States, the Government had argued a position – that the right-of-way was an easement, not a grant of ownership in fee simple subject to a reversionary interest – which was exactly opposite to its position in this case. In Great Northern R. Co. v. United States, the Court found the 1875 Act’s text “wholly inconsistent” with the grant of a fee interest.

Now, the Government was asking the Court to limit Great Northern’s characterization of 1875 Act rights-of-way as easements to the question of who owns the oil and minerals beneath a right of way. But nothing in the 1875 Act’s text supports that reading, and the Government’s argument directly contravenes the very premise of Great Northern: that the 1875 Act granted a fundamentally different interest than did its predecessor statutes. Nor do the Court’s decisions in other cases support the Government’s position, and – to the extent that they could be read that way – the Court said clearly that any such implication did not survive its unequivocal statement to the contrary in Great Northern. Later enacted statutes, such 43 U.S.C. §§ 912 and 940, and 16 U.S.C. § 1248(c), do not define or shed light on the nature of the interest Congress granted to railroads in their rights-of-way in 1875. Instead, those statutes purport only to dispose of interests the United States already possesses.

Now, the Government was asking the Court to limit Great Northern’s characterization of 1875 Act rights-of-way as easements to the question of who owns the oil and minerals beneath a right of way. But nothing in the 1875 Act’s text supports that reading, and the Government’s argument directly contravenes the very premise of Great Northern: that the 1875 Act granted a fundamentally different interest than did its predecessor statutes. Nor do the Court’s decisions in other cases support the Government’s position, and – to the extent that they could be read that way – the Court said clearly that any such implication did not survive its unequivocal statement to the contrary in Great Northern. Later enacted statutes, such 43 U.S.C. §§ 912 and 940, and 16 U.S.C. § 1248(c), do not define or shed light on the nature of the interest Congress granted to railroads in their rights-of-way in 1875. Instead, those statutes purport only to dispose of interests the United States already possesses.

The land patent Marvin Brandt obtained in 1976 included ownership of the land under the railroad company easement. When that easement was abandoned, Mr. Brandt obtained the exclusive right of possession to the land he already owned.